Benjamin Nathan Cardozo (1870–1938), appointed to the Supreme Court in 1932, became one of the most respected jurists to sit on the bench. Benjamin Cardozo is remembered as much for his dissents as for his majority opinions, which often dealt with the application of the due-process clauses of the Fifth and 14th Amendments. He was known as an incrementalist justice who usually supported government positions. He based his judicial decisions according to how they meshed with his views of justice, morality, and social welfare.

Cardozo and his twin sister, Emily, were born into an affluent family in New York City. His early education took place at home, where Horatio Alger, known for his rags-to-riches children’s stories, tutored him. Cardozo entered Columbia College (now Columbia University) at 15 and graduated in 1889 with top honors. After two years of study at Columbia Law School, Cardozo opted to leave and practice law, joining his father’s old firm and passing the bar in 1891.

In 1913 Cardozo was elected to the New York Supreme Court and in 1914 appointed to the state court of appeals. He was appointed chief judge of the appeals court in 1926 and began developing a national reputation as a writer of elegant, persuasive opinions, a pioneer of tort law, and a legal philosopher. Cardozo’s first book, The Nature of the Judicial Process (1920), is a compilation of lectures delivered at Yale University. He subsequently published The Growth of the Law (1924) and The Paradoxes of Legal Science (1928).

Cardozo was a progressive liberal, generally supportive of New Deal legislation

President Herbert Hoover appointed Cardozo to replace the retiring Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. in 1932, two years after the retirement of Chief Justice William Howard Taft, who had earlier opposed a seat on the bench for Cardozo, whom he considered to be too liberal. Cardozo’s nomination received broad approval, and his confirmation made him the second Jew appointed to the Court, Louis D. Brandeis being the first.

Identifying himself as a progressive liberal, Cardozo eschewed partisan politics. He was generally supportive of the constitutionality of most of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal legislation, which was initially resisted by a majority of the justices. The Court’s actions led to Roosevelt’s “Court-packing” effort to increase the number of justices in order to save the New Deal. In the infamous “switch in time that saved nine” — when Justice Owen J. Roberts, who had previously voted against most New Deal programs, began to vote with more liberal members — the Court reversed its position on Roosevelt’s policies.

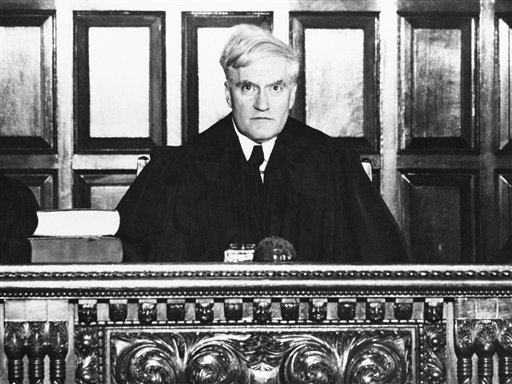

Judge Benjamin Cardozo’s last day in the New York Court of Appeals bench before going to the Supreme Court of the United States in 1932. Cardozo authored more than 100 opinions in his time on the Supreme Court. He also voted in sedition cases that the Court grappled with in the 20s and 30s. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Cardozo was a prolific opinion writer

In his short tenure on the Court, Cardozo wrote more than 100 opinions, including a concurrence in Hamilton v. Regents of the University of California (1934). Joined by Justices Brandeis and Harlan Fiske Stone, Cardozo rejected the notion that California had violated the establishment clause by requiring students to take military science, even in peace-time, without providing exceptions for conscientious objectors. Citing Davis v. Beason (1890), which had upheld state laws punishing polygamists, Cardozo stated that he saw no validity in petitioner’s argument that California had interfered with the free exercise of religion as established in the First Amendment.

In Grosjean v. American Press Co. (1936), Cardozo filed a concurring opinion arguing that the First Amendment’s guarantee of a free press rendered unconstitutional a tax imposed by Louisiana on newspapers that circulated more than 20,000 copies per week. Although some judicial scholars believe that Cardozo’s reasoning in Grosjean was the most innovative civil liberties argument of his career, it was never published. Instead, Justice George Sutherland rewrote his majority opinion to incorporate Cardozo’s arguments.

Cardozo decided sedition cases

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, the Supreme Court grappled with the issue of sedition, as socialism and communism attracted followers in the United States. Although the Court recognized the government’s interest in preventing overt attempts to overthrow the democratic process, the justices maintained a healthy respect for the First Amendment. In fact, First Amendment rights prevailed in most cases of the period through the application of the bad-tendency doctrine, which held speech unconstitutional only if it would likely lead to criminal acts, or the clear and present danger test, which posited that speech was protected unless it precipitated sedition, riots, or destruction of life and property.

Cardozo’s first sedition case on the bench was Herndon v. Lowry (1937), in which a Georgia communist had been convicted of inciting insurrection although a trial court had found Georgia’s statute vague. Cardozo joined the majority in the 5-4 decision, holding that Georgia had violated Herndon’s First Amendment rights because it had failed to prove him guilty of sedition or to show that he had intended to incite insurrection.

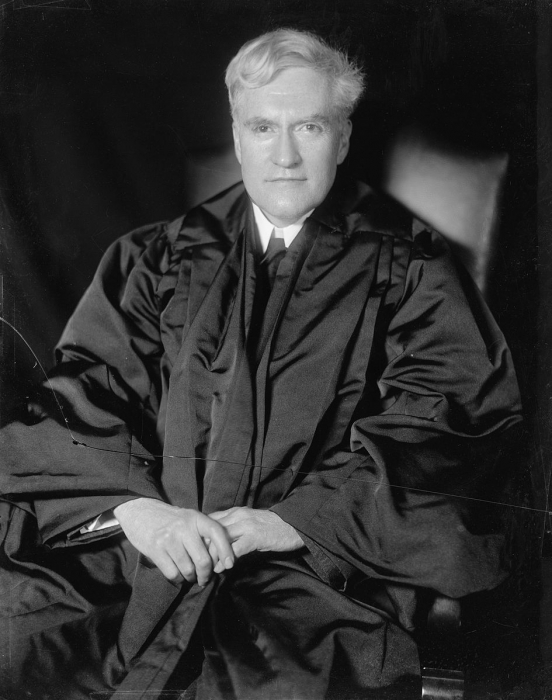

Supreme Court Justice Benjamin Cardozo in 1933. Cardozo was a progressive judge who upheld much of the legislation from Roosevelt’s New Deal program. He was also a strong advocat for free speech. (Public domain.)

Cardozo was a strong advocate of free speech

Cardozo’s position on civil liberties was inconclusive at times, but he nonetheless remained a strong advocate of free speech and accepted the Court’s position in Gitlow v. New York (1925) that the 14th Amendment incorporated the First Amendment, thus binding the states to upholding the latter’s provisions. In Palko v. Connecticut (1937), Cardozo held that the Fifth Amendment’s protection from double jeopardy was not incorporated into the due-process clause of the 14th Amendment. Citing De Jonge v. Oregon (1937) and Herndon v. Lowry (1937) in his Palko opinion, Cardozo reiterated the Court’s position that the 14th Amendment prohibited states from infringing on the right to free speech, which he viewed as the foundation of liberty.

In Associated Press v. National Labor Relations Board (1937), the Court heard a plea from the Associated Press (AP), attempting to use the First Amendment to justify its firing of an employee for engaging in union activities. The AP further insisted that the National Labor Relations Board, as empowered by the National Labor Relations Act to protect labor organizers, exceeded Congress’s power to regulate commerce. Cardozo joined the majority in upholding the National Labor Relations Board on economic grounds rather than voting with conservatives, who would have upheld the right of the Associated Press to fire employees on First Amendment grounds.

Cardozo’s tenure on the Court was short, beginning in 1932 and ending with his death on July 9, 1938, after a paralyzing stroke the previous January.

This article was originally published in 2009. Elizabeth Purdy, Ph.D., is an independent scholar who has published articles on subjects ranging from political science and women’s studies to economics and popular culture.