Commercial speech is a form of protected communication under the First Amendment, but it does not receive as much free speech protection as forms of noncommercial speech, such as political speech.

Commercial speech, as the Supreme Court iterated in Valentine v. Chrestensen (1942), had historically not been viewed as protected under the First Amendment. This category of expression, which includes commercial advertising, promises, and solicitations, had been subject to significant regulation to protect consumers and prevent fraud. Beginning in the 1970s, however, the Supreme Court gradually recognized this type of speech as deserving some First Amendment protection.

Supreme Court cases extending First Amendment to commercial speech

In Bigelow v. Virginia (1975), the Supreme Court ruled that an individual had the right to advertise in Virginia the availability of abortion services in New York although the procedures were at the time illegal in Virginia. Justice Harry A. Blackmun observed, “The existence of commercial activity, in itself, is no justification for narrowing the protection of expression secured by the First Amendment.”

Shortly thereafter in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy v. Virginia Citizens Consumer Council, Inc. (1976), the Supreme Court extended First Amendment free speech protection to commercial speech. Writing for the Court in striking down a state law making it illegal for pharmacies to advertise the price of drugs, Justice Blackmun asserted that the First Amendment not only includes the right of the speaker to speak but also right of the listener to receive information. In this case, consumers had a right to receive lawful information about drug prices.

Moreover, the Court also noted that speech does not lose its protection simply because money is transacted through it. To support that claim, the Court cited political communications involving political contributions and expenditures. Thus, Blackmun concluded that commercial speech, even a communication such as advertising, which merely suggests a business transaction, is protected by the First Amendment. Blackmun also noted, however, that simply because this type of speech is protected speech does not mean that it is immune from government regulation. This type of speech is entitled to less protection than political speech and can be regulated if false or misleading. Unlike with political speech, the truth of which may be difficult to ascertain, the Court thought commercial advertising to be more objective and thus subject to determination of its truth content.

Development of the Central Hudson test

In Central Hudson Gas and Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980), the Court sought to determine how far the regulation of commercial speech can go before it runs afoul of the First Amendment.

In this case, the justices proposed a test in which a court must first decide whether the expression is fraudulent or illegal. If the speech is fraudulent or illegal, the government can freely regulate it without First Amendment constraints. If it is not, then the court must ask whether the asserted governmental interest is substantial. If both questions are answered yes, the court must determine whether the regulation directly advances the governmental interest asserted and whether it is more extensive than is necessary to serve that interest. If the regulation is narrowly tailored to secure the interest, then the regulation of the commercial speech will be upheld.

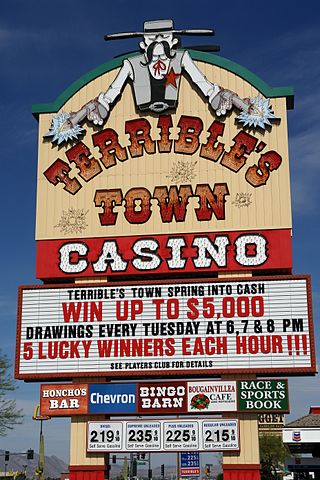

Using the four-pronged Central Hudson test to determine if a regulation of commecial speech could be upheld, the Court in Posadas de Puerto Rico Associates v. Tourism Company of Puerto Rico (1986) upheld a Puerto Rico law that barred casinos from advertising to its residents. The Court found that the interest of Puerto Rico in preventing its residents from receiving these advertisements furthered the narrowly drawn governmental interest of preventing gambling and to protect their health, safety, and welfare. This image is of a casino sign in Henderson, Nevada. (Image via Alex Proimos on Wikimedia Commons, CC BY 2.0)

Court upholds ban on casino advertising; invalidates other regulations

Using the four-pronged Central Hudson test, the Court in Posadas de Puerto Rico Associates v. Tourism Company of Puerto Rico (1986) upheld a law in Puerto Rico that barred casinos from advertising to its residents. The Court found that the interest of Puerto Rico in preventing its residents from receiving these advertisements furthered the narrowly drawn governmental interest of preventing gambling and to protect their health, safety, and welfare.

In 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island (1996), the Supreme Court used the same four-pronged test to strike down a state law prohibiting the advertising alcohol prices. As in Virginia State Board of Pharmacy, the Court ruled that the right of consumers to receive truthful product information about prices was protected speech and that the state interest in promoting temperance was not narrowly drawn enough to prevent consumers from receiving lawful and truthful information about prices.

Through the Central Hudson test, courts across the country have invalidated numerous laws regulating commercial speech. As a result, doctors and lawyers may now advertise, and many companies and businesses, such as pharmaceutical manufacturers, are able to communicate information to consumers about their products so long as the information is truthful and legal.

This article was originally published in 2009. David Schultz is a professor in the Hamline University Departments of Political Science and Legal Studies, and a visiting professor of law at the University of Minnesota. He is a three-time Fulbright scholar and author/editor of more than 35 books and 200 articles, including several encyclopedias on the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court, and money, politics, and the First Amendment.