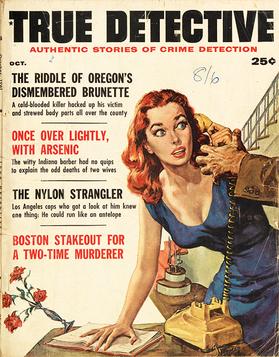

The Supreme Court decision in Winters v. New York, 333 U.S. 507 (1948), overruled a New York obscenity law under which Murray Winters had been convicted for possessing magazines that he intended to sell.

The Court decided that the obscenity statute prohibiting distribution of publications “principally made up of criminal news, police reports or accounts of criminal deeds or pictures or stories of deeds of bloodshed, lust or crime” was overly vague and trenched on First Amendment rights.

Court said state obscenity law was overly vague, violated First Amendment

Justice Stanley F. Reed’s opinion for the Court observed that the law included within its prohibition materials like “detective stories, treatises on crimes, reports of battle carnage, et cetera,” which, on their face, were protected by the First Amendment. In oft-cited language, Reed wrote: “What is one man’s amusement, teaches another’s doctrine. Though we can see nothing of any possible value to society in these magazines, they are as much entitled to the protection of free speech as the best of literature.”

Observing that crimes “must be defined with appropriate definiteness,” Reed wrote that while the present prosecution involved “only vulgar magazines . . . [t]he next may call for decision as to free expression of political views in the light of a statute intended to punish subversive activities.”

Even though New York courts had attempted to limit the reach of the law, Reed reasoned the law remained “too uncertain and indefinite to justify the conviction of this petitioner.” Reed noted that a law dealing with “massed” stories had “no technical or common law meaning,” and that, as a consequence, an “honest distributor” of such materials could not “know when he might be held to have ignored such a prohibition.”

Dissent argued that states were entitled to decide what written materials could provoke crime

In a fairly long dissent joined by Justices Robert H. Jackson and Harold H. Burton, Justice Felix Frankfurter pointed out that such laws had been in existence for more than 60 years in more than 20 states.

States clearly had an interest under their police powers in preventing crime, and legislatures were entitled to exercise their judgment that written materials might play a role similar to spoken words in provoking it. In an argument that seems to portend modern arguments over violent video games or the sale of playing cards of serial killers (Reiter 1998), Frankfurter thought there was special cause for legislators to think that such violent materials might prompt adolescent boys to violence.

Many laws were vague but were appropriately enforced by juries and judges.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.