The Supreme Court decision in Prince v. Massachusetts, 321 U.S. 158 (1944), upheld a Massachusetts regulation that prohibited boys younger than age 12 and girls younger than age 18 from selling newspapers in streets and public places, finding it was not in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment’s free exercise of religion clause.

Prince challenged law that convicted her for taking her niece to sell religious literature

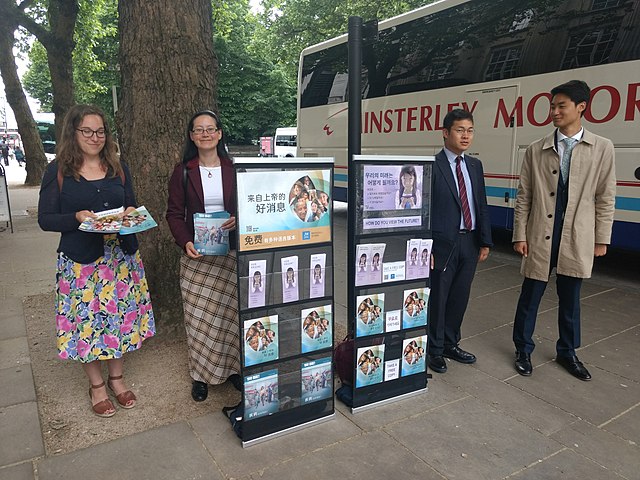

The law and conviction were challenged by Sarah Prince, who had taken Betty Simmons, a nine-year-old niece over whom she had custody, with her to sell literature produced by the Jehovah’s Witnesses. Because she regarded freedom of the press as “secular,” Prince had refused to bring her case on free press grounds and relied on her religious rights, on her rights as a guardian, and on equal protection grounds.

Court said rights of parents and children to exercise religion was not absolute

Justice Wiley B. Rutledge, writing the majority opinion for all but two members of the Court, recognized that past cases had established the rights of parents and children to exercise religion, but he cited laws requiring compulsory vaccination as an indication that such freedom was not absolute. He noted that although adults had the right to make martyrs of themselves, they had no similar right to make martyrs of their children.

Justice Robert H. Jackson agreed that precedents supported the decision but that they were mistaken in not drawing clearer lines between purely religious activities and those, like this, which also involved making money.

Dissent thought the activity in question was religious, not secular

In dissent, Justice Frank W. Murphy, who had urged the Court to accept the case and who often sided with Jehovah’s Witnesses, thought there was no question that the activity was “a genuine religious, rather than commercial, activity.” He thought the state was attempting to control religious activities “under the guise of enforcing its child labor laws.” Murphy believed that “[t]he sidewalk, no less than the cathedral or the evangelist’s tent, is a proper place, under the Constitution, for the orderly worship of God.” He intoned, “Religious freedom is too sacred a right to be restricted or prohibited in any degree without convincing proof that a legitimate interest of the state is in grave danger.”

An example of a relatively rare judicial loss for Jehovah’s Witnesses, the exception to religious liberty that this decision carves out deals narrowly with the rights of juveniles. Hayden C. Covington brought this case on behalf of the Jehovah’s Witnesses.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.