The gravity of the evil test is a refinement of Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s clear and present danger test for determining when the First Amendment right of free speech may be subject to criminal prosecution.

Judge Hand crafted the test based on the gravity of danger and its probability

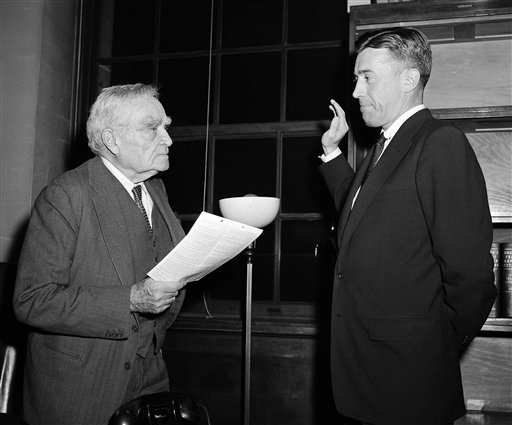

Judge Learned Hand, in United States. v. Dennis (2d Cir. 1950), originally crafted the new test in a federal appellate decision examining the prosecution of officers of the Communist Party of the United States for espousing the revolutionary overthrow of the government. Chief Justice Frederick M. Vinson’s plurality opinion adopted the test in the Supreme Court’s own decision on appeal in Dennis v. United States (1951).

Under the clear and present danger standard, regulation of speech is possible where “the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent.” But the requirement that a danger be present, often defined to mean imminent, rendered awkward Cold War era prosecutions under the Smith Act of 1940, since few if any Communist sympathizers were advocating imminent violence.

Judge Hand’s refinement directs courts to ask “whether the gravity of the ‘evil,’ discounted by its improbability, justifies such invasion of free speech as is necessary to avoid the danger.” Judge Hand is famed for bringing economic thinking such as cost-benefit analysis into the process of legal reasoning. The almost algebraic quality of his analysis in Dennis reflects that approach — gravity multiplied by probability yields a given quantum of danger. Mathematically, even a small probability could justify suppression of speech, if the supposed harm is grave enough.

Free speech advocates had considered Hand a judicial hero in light of opinions such as that in Masses Publishing Co. v. Patten (S.D.N.Y. 1917). Nevertheless, in the immediate postwar period, Hand thought it reasonable to believe the Communist Party was a “conspiracy [which] create[d] a danger of the utmost gravity and of enough probability to justify its suppression.” The Supreme Court agreed.

Some complained the new test distorted the clear and present danger test

Justice William O. Douglas, reflecting the opinion of most civil libertarians, later complained that Hand’s new test was “distorting the ‘clear and present danger’ test beyond recognition,” and that in Dennis and elsewhere, “the threats were often loud but always puny and made serious only by judges so wedded to the status quo that critical analysis made them nervous.”

The gravity of the evil test — or the not improbable test — has occasionally been referenced in subsequent years, including in the Supreme Court case of Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart (1976). However, both the clear and present danger test and its grave though improbable variant have been replaced by the standard established in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), under which speech can be criminalized only upon a showing that it constituted intentional advocacy of imminent and likely lawlessness.

This article was originally published in 2009. Ronald Steiner (Ph.D. Political Science, University of Minnesota; J.D., University of Southern California) is Professor and Director of Graduate Legal Education at the Fowler School of Law at Chapman University, where he teaches constitutional law and other topics in law and political science.