Laws that prohibit discrimination based on race, sexual orientation, ethnicity and religion are sometimes challenged for limiting a person’s or an organization’s free speech rights, rights of association or rights to freely exercise their religion. Anti-discrimination laws have also been passed to prevent discrimination based on a person’s appearance, such as hair length.

Policies that seek to restrict speech based on content, rather than the context in which the speech occurs, generally do not pass constitutional muster. Lower courts have struck down as overly broad university regulations that sought to minimize or prohibit offensive speech on campus in such a way that limited the ability of students or faculty to discuss the effects of biological sex differences or competing views on whether homosexuality could be “cured” through psychological counseling.

In other instances, anti-discrimination laws are challenged by groups that believe that the provisions of those laws infringe upon speech or associational rights.

Jaycees policy of excluding women violated anti-discrimination law

In a major case pitting associational rights against a state anti-discrimination law, the United States Jaycees’ argued that the use of the Minnesota Human Rights Act to prevent it from continuing its policy of excluding women from membership limited their associational rights under the First Amendment, as it forced them to “associate” involuntarily with women. The Supreme Court disagreed.

In Roberts v. United States Jaycees (1984) the Supreme Court acknowledged that the right to associate necessarily implied a right not to associate. But it also held that the right was not absolute and that a compelling state interest might justify a policy narrowly tailored to serve that interest. The elimination of certain forms of invidious discrimination, including sex discrimination, was sufficiently compelling to meet the standard.

The court also concluded that compliance with the Minnesota law neither altered the Jaycees’ message nor impaired its ability to express its views.

In Hishon v. King & Spalding, 467 U.S. 69 (1984), the court refused to allow a law firm’s associational rights to exempt its partner promotion decisions from requirements of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 prohibiting discrimination on the basis of sex.

Supreme Court ruled Boy Scouts can exclude homosexuals

The court adopted a very different stance about a policy of the Boy Scouts of America that prohibited homosexuals from membership.

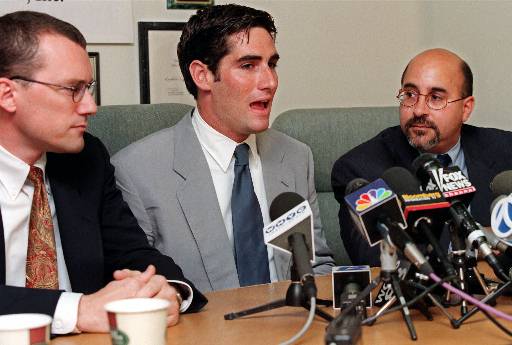

The Boy Scouts had revoked the adult membership of James Dale upon learning of his open homosexuality. Dale filed suit under the New Jersey public accommodations law, which prohibits discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation in places of public accommodation.

In Boy Scouts of America v. Dale (2000), the Supreme Court distinguished the case from Roberts, noting that the Boy Scouts promulgated a specific moral message that it asserted was inconsistent with homosexual conduct.

Were the Boy Scouts to be required to accept Dale as a member, they would be compelled to support a moral position inconsistent with the message, values and goals of the organization. While a group may be compelled to extend the benefits of membership to an undesired group, it may not be compelled to deliver a message contrary to its actual views. Thus, the New Jersey law infringed on the Boy Scouts’ expressive associational rights in violation of the First Amendment.

Gay marriage set off new challenges to anti-discrimination laws

After gay marriage became legal nationwide in 2015 (Obergefell v. Hodges, 576 U.S.), a number of wedding-related businesses sought to deny services to gay couples, running afoul of anti-gay discrimination laws.

In New Mexico, a photography studio, Elane Photography, argued that forcing it to photograph gay weddings violated its First Amendment right not to speak and to the free exercise of religion.

New Mexico’s highest court rejected the idea that the state was “compelling” speech and ruled that the photography studio violated the state’s Human Rights Act in Elane Photography v. Willock, 309 P.3d 53 (2013).

The U.S. Supreme Court denied an appeal to review the photography studio case, but later took up a similar issue in Masterpiece Cakeshop v. Colorado Civil Rights Commission (2018). In Masterpiece Cakeshop, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the right of a cakeshop owner, a devout Christian, who refused based on his religious beliefs to design a custom cake for a same-sex wedding. The court’s opinion noted that the cake-maker had not refused to sell all of his non-custom cake products to gays but instead argued he should not be forced “to use his artistic skills to make an expressive statement” endorsing same-sex marriage with a custom cake. The court also heavily weighted remarks by the state’s civil rights commission that had found probable cause against the cake shop in violating the state’s anti-discrimination laws. The court observed that the commission expressed negative animus toward the owner’s religious beliefs rather than treating those beliefs with neutrality required by the First Amendment.

Most recently, in 2021, the Supreme Court in Fulton v. City of Philadelphia upheld the First Amendment religious rights of Catholic Social Services, saying the agency’s religious-based refusal to certify same-sex couples as foster families could not be the city’s reason for ending the agency’s long-held foster care placement contract. The city had said the agency violated the non-discrimination requirements in the foster care contract.

Some states, cities bar discrimination based on hair length and style

Some states and cities have enacted laws to prevent discrimination based on appearance, such as hair length or style. For example, Texas enacted the CROWN Act to prevent that bars employers and schools from penalizing people because of hair texture or protective hairstyles including Afros, braids, dreadlocks, twists or Bantu knots.

However, courts have generally ruled that employers and schools have a right to regulate appearance, such as hair length, as long as the regulations are related to legitimate business or governmental objectives. The Supreme Court has not taken up the issue, but lower courts have split over whether hair length may be treated as symbolic speech. Courts have also ruled that hair regulations must not infringe upon religious liberty.

This article was first published in 2009 and has been periodically updated by encyclopedia staff, most recently in December 2023. Sara L. Zeigler wrote the original 2009 article. She is the dean of the College of Letters, Arts, and Sciences at Eastern Kentucky University.