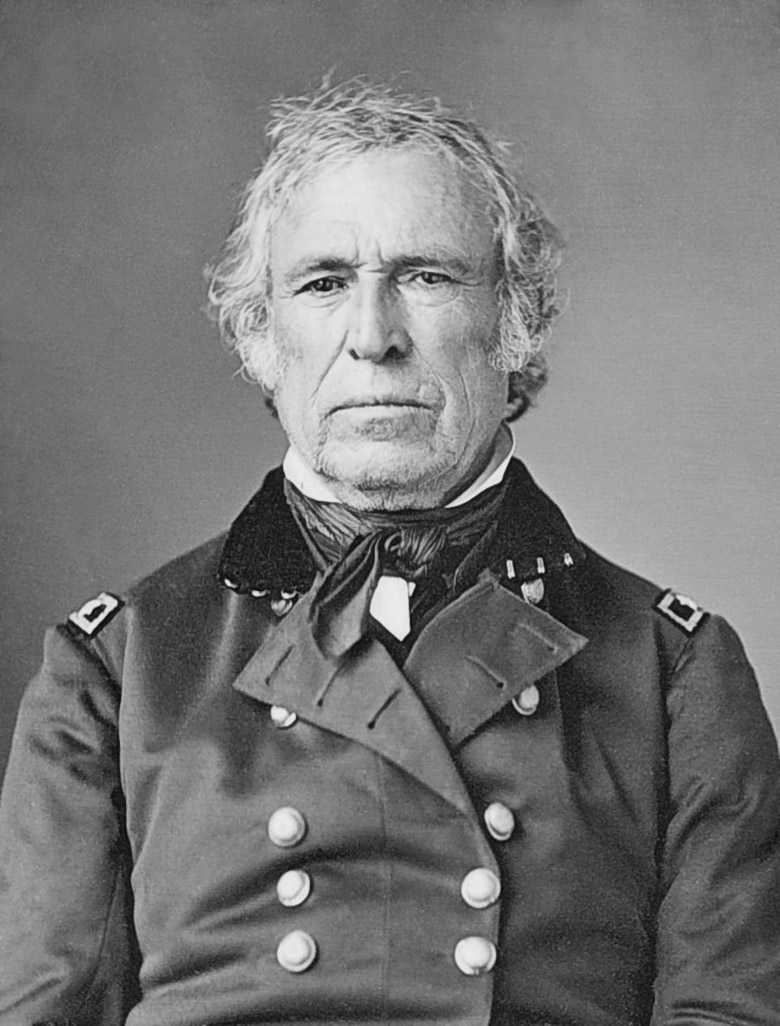

Zachary Taylor (1784-1850) was born in Virginia, largely raised in Kentucky, and claimed Louisiana as home. He spent most of his life in the U.S. Army where he became a major general and hero of the Mexican-American War.

He was elected president as a Whig in the election of 1848, with Millard Fillmore as his running mate. He followed James K. Polk, a Democrat, who had not run for reelection, into that office. Taylor and Fillmore defeated Democrats Lewis Cass of Michigan and William O. Butler of Kentucky as well as former president Martin Van Buren, who was running as a Free Soil candidate. Although he ran as a Whig, Taylor viewed himself as being above parties (Greenstein and Anderson, 2013, 34).

Because Taylor served only about 16 months in office before dying of a stomach ailment, probably gastroenteritis, he did not have much of an impact on the First Amendment. Nor do there appear to have been any important Supreme Court decisions on the subject during his presidency. Taylor’s presidential election has the distinction of being the first such election ever to be declared by the Associated Press (Olson and Koenig 2020).

A war hero, Taylor pledged his guide would be the Constitution

In his inaugural address, Taylor pledged that his guide would be “the Constitution, which I this day swear to ‘preserve, protect, and defend’” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 100). He further pledged that “For the interpretation of that instrument I shall look to the decisions of the judicial tribunals established by its authority, and to the practice of the Government under the earlier Presidents, who had so large a share in its formation” (Inaugural Addresses, 199, 100). After noting the blessings that Divine Providence had bestowed on the nation, Taylor had invoked the hope that America would demonstrate its worthiness of such blessings “by prudence and moderation in our councils, by well-directed attempts to assuage the bitterness which too often marks unavoidable differences of opinion, by the promulgation and practice of just and liberal principles, and by an enlarged patriotism, which shall acknowledge no limits but those of our own widespread Republic” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 101).

Taylor favored admission of California, New Mexico as free states

Whigs generally thought that the president should defer to Congress, and Taylor, who had never voted prior to his own election, gave few indications of his own stances on key issues prior to becoming president. To the surprise of many and to the dismay of Southern Whigs, he then favored the admission of both California and New Mexico as free states, which would have tipped the balance in Congress to free states. Taylor also indicated that he would defend the Union through force if this proved to be necessary.

Taylor resisted Utah statehood, which he identified with Mormons whom he reputedly called a “pack of outlaws” (Smith 2009, 591). Brigham Young, in turn, reputedly claimed on Taylor’s death that he was “in hell, and I am glad of it” (Smith 2009, 590, n. 2).

After Fillmore became president upon Taylor’s death, he appointed Brigham Young as president of the Utah Territory. Unlike Taylor, he further approved of the Compromise of 1850, which admitted California without settling on the status of other territories and made a number of concessions to slave states including stricter enforcement of fugitive slave laws.

Taylor did not have occasion to appoint any Supreme Court justices during his tenure as president and his reputation as a general continue to eclipse his reputation as president.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 12, 2023.