In Wooley v. Maynard, 430 U.S. 705 (1977), the U.S. Supreme Court reaffirmed the principle that the government cannot compel individuals to subscribe to certain beliefs.

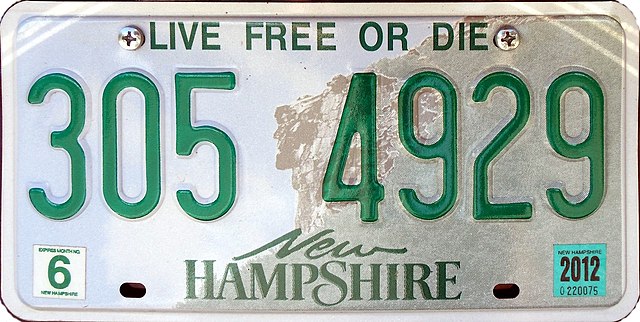

The case involved a New Hampshire law that required license plates to contain the state motto “Live Free or Die” and prohibited individuals from obscuring the motto.

Jehovah's Witness fined for covering state motto on license plate

Jehovah’s Witnesses George and Maxine Maynard objected to the message for religious reasons, and George affixed a piece of red tape over the motto on his license plate. For this action, he was cited multiple times. The first time, a judge fined him $25. The second time, a judge cited him for a $50 fine and, after Maynard refused to pay either fine, sentenced him to 15 days in jail. He was then cited a third time.

The Maynards subsequently filed a federal lawsuit that sought a declaratory judgment that the New Hampshire scheme violated the First Amendment. A three-judge federal district court entered an order, which prohibited the state from punishing the Maynards.

Court said motto was compelled speech, violated First Amendment

On appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court affirmed this ruling by a 6-3 vote. In his majority opinion, Chief Justice Warren E. Burger phrased the issue as “whether the State may constitutionally require an individual to participate in the dissemination of an ideological message by displaying it on his private property in a manner and for the express purpose that it be observed and read by the public.”

The majority considered this question and reasoned that the case presented a classic case of compelled speech.

“The First Amendment protects the right of individuals to hold a point of view different from the majority and to refuse to foster, in the way New Hampshire commands, an idea they find morally objectionable,” Burger wrote. He compared the New Hampshire law to the forced flag salute law, which the U.S. Supreme Court had invalidated in West Virginia Board of Education v. Barnette (1943).

State argued motto fostered state pride, helped vehicle identification

The state had argued the law advanced two interests: facilitating the identification of vehicles and fostering state pride and history. The majority found that the license plate numbers, not the motto, ensured identification of vehicles and rejected the fostering of state pride interest because the state was pursuing its interest by silencing individual views.

Justices Byron R. White and William H. Rehnquist wrote separate dissenting opinions.

Justice White’s dissent focused on procedural matters dealing with whether a federal court injunction should be issued when there were pending state criminal law proceedings.

Justice Rehnquist’s dissent squarely addressed the underlying First Amendment issues. He wrote that the state did not compel the Maynards to “ ‘say’ anything; and it has not forced them to communicate ideas with nonverbal actions reasonably likened to ‘speech,’ such as wearing a lapel button promoting a political candidate or waving a flag as a symbolic gesture.”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.