Using the clear and present danger test, the Supreme Court ruled in Wood v. Georgia, 370 U.S. 375 (1962), that individuals and public officials concerned with ongoing grand jury proceedings may speak freely about the proceedings and can only be charged with contempt of court when their speech immediately creates a serious threat to the administration of justice.

Sheriff criticized local judges for voting investigation

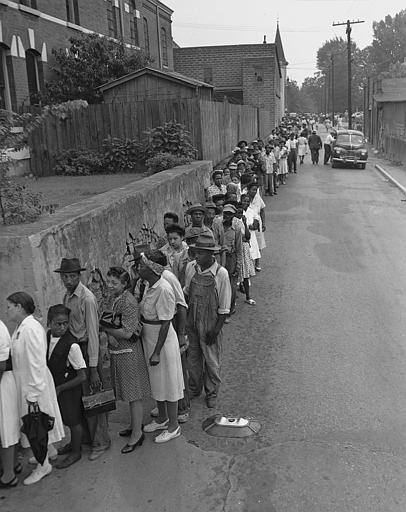

In June 1960, a judge in Bibb County, Georgia, instructed a grand jury to investigate “an inane and inexplicable pattern of Negro bloc voting” and “rumors and accusations” that candidates for public office had paid large sums of money to obtain the black vote. The next day, Sheriff James Woods issued a press release, criticizing the judges, calling the action a “crude attempt at judicial intimidation of negro voters and leaders, or, at best, as agitation for a `negro vote’ issue in local politics.”

Woods was convicted of contempt of court in a bench trial (without a jury) for his harsh criticism of the local trial judges, and a Georgia court of appeals ruling affirmed Wood’s convictions. The Supreme Court reversed.

Court said criticism was protected by First Amendment

The justices unanimously agreed that Bridges v. California (1941) should be applied as precedent. Bridges and the subsequent decisions of Pennekamp v. Florida (1946) and Craig v. Harney (1947) involved nonjury contempt of court charges. In them, the Court moved to limit state judges’ use of contempt powers to punish the press for commenting on pending cases.

Justice Hugo L. Black’s opinion in Bridges restated the clear and present danger test by requiring courts to use as “a working principle that the substantive evil must be extremely serious and the degree of imminence extremely high before utterances can be punished.”

In Wood, Chief Justice Earl Warren’s opinion dismissed Georgia’s claims as speculative because the state did not provide evidence nor witnesses at trial that the publication of the statements hindered the grand jury’s investigation.

In dissent, Justice John Marshall Harlan II noted that sheriffs are also officers of the court and concluded that Georgia reasonably considered Wood’s actions as a clear and present danger to the grand jury investigation.

Court differentiated between grand jury investigations and trials

Warren warned in his majority opinion in Wood that “limitations on free speech assume a different proportion when expression is directed toward a trial as compared to a grand jury investigation” (p. 390). Subsequent rulings in Sheppard v. Maxwell (1966) and Gentile v. State Bar of Nevada (1991) indicate that different standards do apply when jury trials are ongoing because of the constitutional nature of the right to trial by an unbiased jury.

While the reach of the Wood decision may have eroded, Warren’s central conclusion still holds: “[t]he petitioner [Wood] was an elected official and had the right to enter the field of political controversy, particularly where his political life was at stake.”

William L. Gillespie is an Associate Professor of Political Science at Kennesaw State University. This article was originally published in 2009.