The landmark Supreme Court decision in Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972) addressed the constitutional balance between state police power, here a Wisconsin compulsory education statute, and the rights of three members of the Old Order Amish religion and the Conservative Amish Mennonite Church — Jonas Yoder, Wallace Miller, and Adin Yutzy — to educate their children in conformity with their religious beliefs.

Wisconsin families withdrew children from school earlier than law allowed

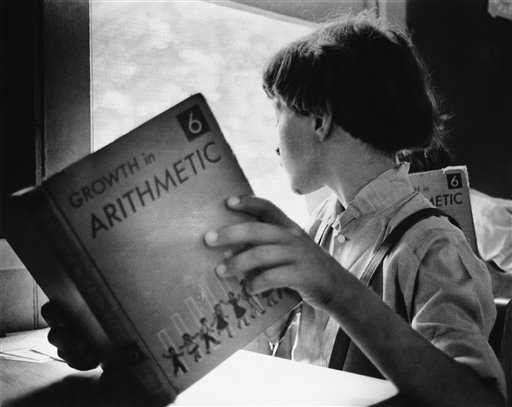

This case arose in New Glarus, Green County, Wisconsin. The Wisconsin compulsory-attendance law required that parents ensure their children attend school until the age of 16. The respondents withdrew their children — Frieda Yoder, age 15; Barbara Miller, age 15; and Vernon Yutzy, age 14 — after the children had graduated from the eighth grade in public school.

The New Glarus school district administrator filed a complaint about this action. Subsequently, the elder Yoder, Miller, and Yutzy were convicted of violating the compulsory-attendance law in Green Country Court. Each was fined $5. Although the trial court found that the Wisconsin law interfered with the defendants’ “sincere religious belief,” it found that the requirement of high school attendance until age 16 was a “reasonable and constitutional” exercise of governmental power. The Wisconsin circuit court affirmed the convictions, but the Wisconsin Supreme Court reversed, holding that Wisconsin had not demonstrated that its interest in “establishing and maintaining an educational system overrides the defendants’ right to the free exercise of their religion.”

Supreme Court ruled in favor of the parents

The U.S. Supreme Court affirmed the state supreme court by a vote of 6-1 (Justices Lewis F. Powell Jr. and William H. Rehnquist had not yet joined the Court when Yoder was argued and did not participate in the decision) and ruled in favor of the Amish parents.

Chief Justice Warren E. Burger wrote the majority opinion. After reviewing the Court’s jurisprudence assaying the state responsibility to provide education in relation to religious liberty, Burger noted: “[H]owever strong the State’s interest in universal compulsory education, it is by no means absolute to the exclusion or subordination of all other interests.” The Court vindicated the Amish view that sending their children to public high school would threaten their mode of life — a way of life derived from a literal interpretation of Paul’s Epistle to the Romans: “do not be conformed to this world” (Romans 12:2).

Court was divided over constitutional interests of the children

Yoder’s constitutional significance has been somewhat eclipsed by an intramural, sidebar, disagreement among the justices. While agreeing with the majority that “the religious scruples of the Amish are opposed to the education of their children beyond the grade schools,” Justice William O. Douglas dissented because “[t]he Court’s analysis assumes that the only interests at stake in the case are those of the Amish parents on the one hand, and those of the State on the other.”

Douglas cast himself as defender of the neglected prerogatives of children (Amish and otherwise): “Our opinions are full of talk about the power of the parents over the child’s education. . . . Recent cases, however, have clearly held that the children themselves have constitutionally protectible interests.” Douglas’s opinion prompted three of his colleagues explicitly to disagree.

This article was originally published in 2009. James C. Foster is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Oregon State University-Cascades.