Like the proverbial trials and tribulations of the Ancient Mariner or the Flying Dutchman, the Voice of America seems destined to sail the boundless sea of government bureaucracy, without ever finding a quiet port.

Or perhaps Odysseus is a better analogy: What started as a short trip homeward turned into an almost never-ending journey. Although at least Odysseus eventually found his way home.

International broadcasting seems to have begun with Guglielmo Marconi in the early 1920s when he sent a shortwave radio signal from Cornwall, England, to the Cape Verde Islands. International circuits were soon connecting London to Australia, India, South Africa and Canada. [Bray, 2002] Soon, shortwave stations carrying a variety of programs were established around the world.

By 1939, confusion reigned as amateurs essentially playing with crude transmitters, universities experimenting with radio and companies interested in maximizing profits with the new medium all operated with little oversight from the government.

In these early days, almost anyone in the United States could obtain a broadcast license from the Commerce Department, which was essentially limited to simply issuing a license, with almost no enforcement authority.

Broadcasters ignored power, time-of-day and frequency allocations, often infringing on revenue-generating advertising from high-powered stations.

To combat these ever-growing problems the Federal Radio Commission was established in 1939, and, in cooperation with the U.S. State Department, created a limitation regarding international broadcasting:

A licensee of an international broadcast station shall render only an international broadcast service which will reflect the culture of this country and which will promote international goodwill, understanding and cooperation. Any program solely intended for, and directed to an audience in the continental United States does not meet the requirements for this service. [Bruère, 1971]

The Voice of America, the U.S. government's international project for teaching other countries about America via shortwave radio, gets a large listener response judging by the 85,000 letters which flooded into the U.S. State Department's international broadcasting division between February, 1946 and February, 1947. Here, Harry Branton holds some mail from Germany, and looks at map trying to locate the small cities where the mail came from, April 9, 1947 in Washington. (AP Photo/Dan Grossi)

The founding of Voice of America

Despite these ideals, it soon became obvious the airwaves could be used, not only for news and information, but also for more nationalistic purposes. Thus, with rise of Adolph Hitler, the Auslandsrundfunk (Foreign Radio Section) became a vital part of Nazi propaganda [Wood, 2000] , and what today we know as the Voice of America was established during World War II to counter Nazi disinformation.

But even at the beginning there were conflicts about the role of the government in disseminating information, particularly since there were two agencies devoted to the dissemination of news and information: The Office of War Information and the Office of Censorship.

Curiously, the names of these two organizations, in fact, were the opposite of what they actually did. The Office of War Information limited the kinds of news it would distribute, while the Officer of Censorship relied on voluntary cooperation from news media outlets in following a voluntary "Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press."

The short life of the Office of the Coordinator of Information

Although these two organizations were established following the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, there was already a government agency broadcasting news and information via shortwave: the Office of the Coordinator of Information, established on July 11, 1941, at the behest of William Donovan and Robert Sherwood.

But immediately there were problems. Donovan, nominally the director of the Office of the Coordinator of Information, was primarily interested in military information and using broadcasts in covert operations and psychological warfare. Sherwood was one of several deputy directors and was also a presidential speech writer specializing in foreign affairs. He wanted to focus on news and information in the area of public diplomacy.

The fledgling organization began broadcasting the week after Pearl Harbor, aiming its programming at the Philippines.

On Feb. 1, 1942, broadcasts to Germany began with the pledge, "Today, and every day from now on, we will be with you from America to talk about the war. ... The news may be good or bad for us - We will always tell you the truth."

Sherwood, incidentally, had already coined the term "Voice of America" for the German-language program titled, Stimmen aus Amerika ("Voices from America")

Relations between Donovan and Sherwood were contentious, and on June 13, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt dissolved the Office of the Coordinator of Information and created two new agencies: the Office of Strategic Services, later to become the Central Intelligence Agency, and the Office of War Information, which took over the Voice of America, and later became the United States Information Agency.

Voice of America under Office of War Information during WWII

By the end of the war, the Voice of America was transmitting more than 1,000 programs consisting of news, information, music and commentary in 40 languages using 39 transmitters.

In addition to creating its own programming, the Voice of America also retransmitted programs created by the national networks. For example, the Voice of America picked up the CBS music program “Viva America,” which aired from 1942 to 1949.

But just as the end of the war brought an overall downsizing of the military, likewise the Voice of America was reduced by about half, and in 1945 its operations were transferred to the State Department.

Voice of America under the State Department during Cold War

These developments — the end of the war but the almost immediate shift to the Cold War, and the transfer to the State Department — began a series of on-again, off-again programming and language changes, as the agency responded to a never-ending series of international developments, some positive and some negative.

One can only imagine the international confusion on the part of audiences as long-running programs in a particular language, or aimed at a particular geographic area, were suddenly no longer available, and programming in a new language and new regional area began.

As noted earlier, the Voice of America began international operations as part of the America's international diplomacy even before the end of World War II, albeit not aimed specifically at the Soviet Union.

Thus began a series of tit-for-tat broadcasts between the United States and the Soviet Union.

If there can be a starting date for the Cold War, Winston Churchill's "Iron Curtain" speech on March 5, 1946, at Westminster College, Fulton, Missouri, would be in contention: "From Stettin in the Baltic to Trieste in the Adriatic an iron curtain has descended across the Continent."

At the start of the Cold War, however, the Soviet Union began its own short wave international broadcasts aimed specifically at the United States.

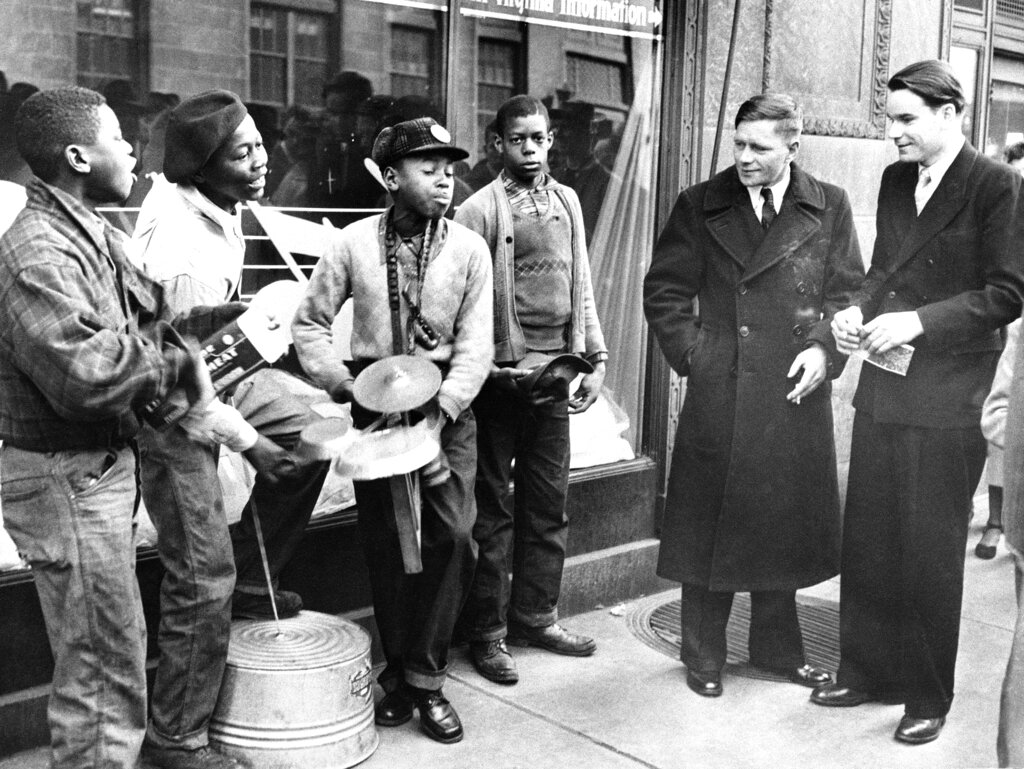

Russian fliers Anatole Barsov, second from right, and Piotr Pirogov stop on a street in Richmond, Va., to listen to southern washtub band "The Ramblers" onn Feb. 5, 1949. The fliers, who defected from the Soviet Union in a plane, visit Virginia after hearing a Voice of America broadcast about the state. (AP Photo)

Voice of America broadcasts targeted to Soviet Union

These attacks were countered beginning in February 1947 when the United States began specifically targeting the Soviet Union. Here one can also see a subtle shift in programming from straight news and information to commentary and propaganda.

At first these programs were confined almost entirely to music and straight news reports, but gradually more time was devoted to answering Soviet attacks considered hostile to the United States or harmful to its national interests.

Philosophically, the broadcasts were considered an act of self-preservation, going all the way back to Chief Justice John Marshall in 1804:

The authority of a nation within its own territory is absolute and exclusive [and] its power to secure itself from injury, may certainly be exercised beyond the limits of its territory. ... These means do not appear to be limited within any certain marked boundaries, which remain the same at all times and in all situations. ... If they are such as are reasonable and necessary to secure their laws from violation, they will be submitted to. [Church v. Hubbart, 6 U.S. 187, 234 (1804) ]

The need to counter Soviet propaganda with its own messages, however, ran into memories of Nazi propaganda aimed at German citizens themselves. These perhaps conflicting concerns led to the passage of the United States Information and Exchanger Act, better known as the Smith-Mundt Act (Public Law 402), which called for the government to "to promote a better understanding of the United States in other countries..." However, at the same time, the law instructed the State Department "to provide for the preparation, and dissemination abroad of information about the United States ... through ... radio." (emphasis added).

Coast Guard Ensign Henry H. Lodge, looks over big glass tubes of a high voltage rectifier unit aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Courier, near Washington, D.C., March 2, 1952. President Truman will inaugurate the Courier as a floating Voice of America radio station on March 4. The Courier will operate in waters close to Russia. (AP Photo/Harvey Georges)

Voice of America fights against international communism

In response, on April 24, 1949, the Soviet Union began deliberate jamming of Voice of America broadcasts and soon had more than 1,000 transmitters trying to block the incoming material.

In 1949, Foy Kohler took over as Voice of America director and saw the organization's primary purpose to be the fight against international communism, particularly in France and Italy. In addition, some American news reports indicated the Voice of America was instrumental in convincing people in the Soviet Union to defect. Said a Soviet sailor who defected by jumping ship in Calcutta harbor and asked for asylum on a nearby American ship and then testified before the House Committee on Un-American Activities:

I came to understand [through the Voice of America] that America is the leading country of the free world. I became convinced that people there really are equal under the law and that each person is able to build his own life without directives from above. [Congressional Record, Sept. 23, 1963, p. 5978, citing Robert K. Walsh, Sept. 19, 1963, "Russian Ship Jumper Hails Voice Programs," Washington Evening Star.]

It was during this time that one of the strangest episodes in Voice of America history took place. From August 1952 through May 1953, a high school student, Billy Brown, hosted what today would be considered a podcast, as his Monday evening "chatty narratives" recounted life in Yorktown Heights, New York, "just a simple glimpse in simple language into the soda fountains, the basketball games, the classrooms and the farmhouse kitchens."

Unfortunately, he became a victim of his own success, as he received so much fan mail from overseas the agency couldn't provide the $500 for clerical and postage support to answer all of the mail.

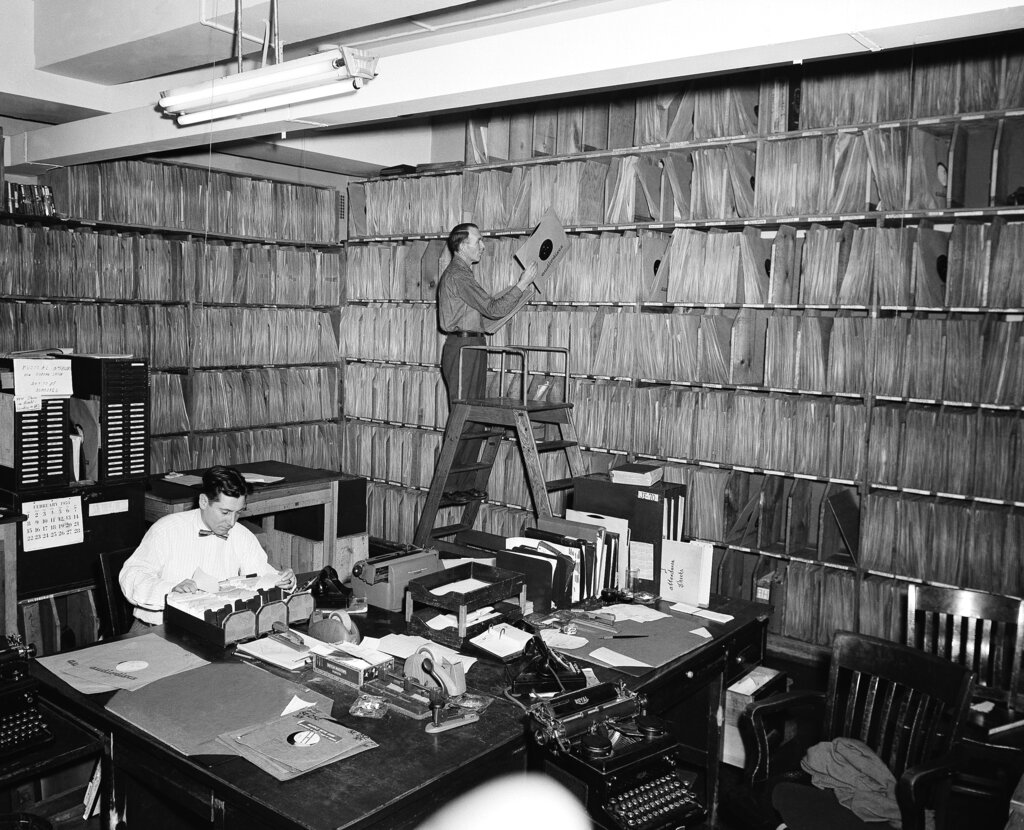

The city room and record library at the New York office of Voice of America is shown, Feb. 27, 1953. (AP Photo/John Rooney)

Voice of America under the U.S. Information Agency

On Aug. 1, 1953, President Dwight D. Eisenhower created the U.S. Information Agency, which assumed Voice of America control from the State Department.

As part of the State Department, the Voice of America had been the primary international news outlet for news and information. Now, under the U.S. Information Agency, the Voice of America was merely one of several news and information functions, including libraries and exhibits in foreign countries, a print-oriented news service, and a motion picture division designed to work with Hollywood in producing pro-American theatrical features.

But despite the obvious pro-American slant to the information agency’s activities and Voice of America programming, the organization still came under scrutiny by Sen. Joseph McCarthy and his aides Roy Cohen and Gerard David Schine. Apparently, the broadcasts may have been pro-American but were not pro-American enough.

For example, although Voice of America was building extra transmitters to enhance their coverage, the transmitters were said to be too weak to be effective. It also appears the hearings were for the most part opportunities for disgruntled employees to voice criticisms of technical issues, management and news content. [Heil, 2003]

Nevertheless, a series of unproductive hearings were conducted in February and March 1953 before McCarthy and his team moved on to more potentially fruitful investigations. [Risen, 2025]

The deployment of the transistor in the 1950s allowed the Voice of America to further expand its offerings, but even here there was confusion and uncertainty.

For example, during the Hungarian uprising against Soviet domination in 1956, nationalist partisans thought the routine news and information broadcasts were, in fact, a cover for direct American aid.

Theodore C. Streibert, seated, director of the newly formed independent United States Information Agency, and Leonard F. Erikson, the new head of Voice of America, talk things over in the master control room of Voice in New York, Sept. 3, 1953. Streibert, 51-year-old former New York radio executive, lost no time reorganizing the agency after he took office. The USIA announced Aug. 27, it was chopping 2,000 persons from its staff of 8,000 and would eliminate all but the most important of its overseas activities. (AP Photo/Ed Ford)

Foreign jamming of Voice of America broadcasts

One of the issues that caused debate and confusion was the subject of jamming by Soviet satellite countries. Depending on one's point of view, the jamming was seen as a demonstration of how effective the broadcasts could be, or the jamming was completely interfering with the broadcasts, so why pay for them.

For example, Poland stopped jamming the broadcasts in 1956 (perhaps indicating the programs were having no impact on Polish citizens) but Bulgaria continued jamming activities through the 1970s (indicating the broadcasts were effective and had to be stopped).

Said Edward R. Murrow, director of the U.S. Information Agency from 1961 to 1964:

The Russians spend more money jamming the Voice of America than we have to spend for the entire program of the entire Agency. They spend about $125 million [$1.2 billion in 2024] a year jamming it. ["Postal Rate Revision of 1962: Hearings Before the Committee on Post Office and Civil Service, United States Senate, 87th Congress Feb. 1962]

Murrow further pointed out that although the Soviets used more than 1,000 jamming transmitters, they had never been completely successful in blocking the broadcasts.

Three former residents of Czechoslovakia tell Czechs through the Voice of America, September 6, 1951, show how communist leaders of that country sent Associated Press correspondent William N. Oatis to prison. Left to right during one of six broadcasts called "Witness for the defense" are Jaroslav Drabek, Helen Kolda and Joseph Sadlik. Voice of America broadcasts in many other languages are to follow. (AP Photo)

Interaction with Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty

It should be noted that the confusion over roles, missions and scope of the Voice of America was not limited to the U.S. government and was further compounded by what appears to be a competing radio system, Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty.

This is not the place for a full discussion of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, except to briefly illustrate that when discussion the Voice of America and its "competitor" in Europe, "Perceived reality is reality, " and "When perception becomes reality, reality becomes irrelevant."

So, we've already seen testimony as to the impact and importance of Voice of America. However, in a 2004 conference sponsored by the Hoover Institution and the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars at Stanford University, praised the work of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty and notes, "[A]ccording to [Mark] Pomar, [president of the International Research and exchange Board in Washington, D.C.] in the1980s Voice of America (VOA) Russian programming was not particularly exciting and was not generating a large audience." [Hoover conference] Yet a few sentences later the report says:

By demonstrating that dissidents like Rostropovich and Solzhenitsyn were important cultural icons in the West, VOA enhanced the average Soviet citizen's view of the United States. These interviews especially resonated with Russian listeners, generating excitement that raised morale within the VOA service.

The report also seems to indicate there was a lack of government funding and government control of Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty: "In addition, RL had a Board led by Malcolm (Steve) Forbes that protected it from interference from the State Department, Congress, and elsewhere."

But Cord Meyer, an aide to CIA director Richard Helms said:

"In September 1954 ... both radio stations formed part of the operations covertly funded by the CIA. ...It was not until 1971 that the widely held belief that these two organizations [RFE and RL] received most of their funds from the CIA was officially confirmed..." [Cord,2000]

The convoluted nature of this over-the-air warfare is illustrated by the fact that on July 6, 2003, the Voice of America began news and commentary in Farsi-language broadcasts to Iran. Almost immediately jamming from transmitters located near Havana, Cuba, began blocking the television signals.

This is the Voice of America building in Washington D.C., on Monday, May 5, 2025. (AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar)

Expansion of foreign-language broadcasts

With the dissolution of Soviet hegemony in 1989, the subsequent breakup of the Soviet bloc, and the end of the Cold War, the Voice of America embarked on an expanded program of foreign-language broadcasts to Eastern Europe and Asia. There was, however, a continuing series of programming changes, undoubtedly leading to some confusion on the part of listening audiences.

The Voice of America in 2025 broadcasts in 49 languages, reaching an estimated weekly audience of 361 million people.

The administrative musical chairs continued in 1994, when the Clinton administration and the International Broadcasting Act created the International Broadcast Bureau under the auspices of the United States Information Agency The act also provided for oversight from a newly created a Broadcasting Board of Governors.

These changes, however, lasted only until 1998, with the passage of the Foreign Affairs Reform and Restructuring Act which abolished the U.S. Information Agency, and moved most of its various functions, including the Voice of America, to the State Department. The Broadcasting Board of Governors also became an independent federal agency.

Nevertheless, with the world-wide expansion of the internet, which in effect erased national borders, it became almost impossible to limit broadcast signals from being imported or intercepted by anyone in the world. Thus, the Smith-Mundt Modernization Act provision of the National Defense Authorization Act for 2013 allowed audiences within the United States to access Voice of America internet programming.

With the two presidencies of Donald Trump (2017-2021 and 2025-present), the mission and scope of Voice of America operations have been marked by confusion and partisanship.

What can be said for certain is that the budget and staffing have been significantly reduced from previous years, including proposals for the complete elimination of the Voice of America and related agencies, including, for example, the Public Broadcast Service (PBS). In addition, there has been an almost constant turnover in upper management.

Many of these changes and proposals are split along party and ideological lines, and in some cases harken back to the Red Scare and McCarthy eras.

Liberals and Voice of America staffers see the role of the agency as presenting news and information. Cost-cutting and staff reductions are seen as attempts to control content and specifically to promote a conservative agenda.

Conservatives, particularly those outside the Voice of America, on the other hand, see the agency as overrun with anti-American and anti-conservative management and staff.

Interestingly, these debates reflect the very founding of the Voice of America, when questions of role and scope were being debated. As an arm of the government, should the Voice of America only reflect government ideas and positions? And should the government fund an agency representing the ideals of the First Amendment: free and open debate and discussion?

Larry Burriss, Ph.D., JD, is a professor in the School of Journalism and Strategic Media at Middle Tennessee State University.