Upton Sinclair (1878-1968) was a muckraking journalist, prolific novelist, and socialist political activist who ran unsuccessfully for governor of California as a Democrat in 1934. His most notable work was “The Jungle,” which detailed unsanitary and unfair labor practices in the meat-packing industry, was partly responsible for the adoption of the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906 and the Meat Inspection Act.

Sinclair also received a Pulitzer Prize in 1943 for his historical novel “Dragon’s Teeth,” which dealt with Adolph Hitler’s rise to power in Germany.

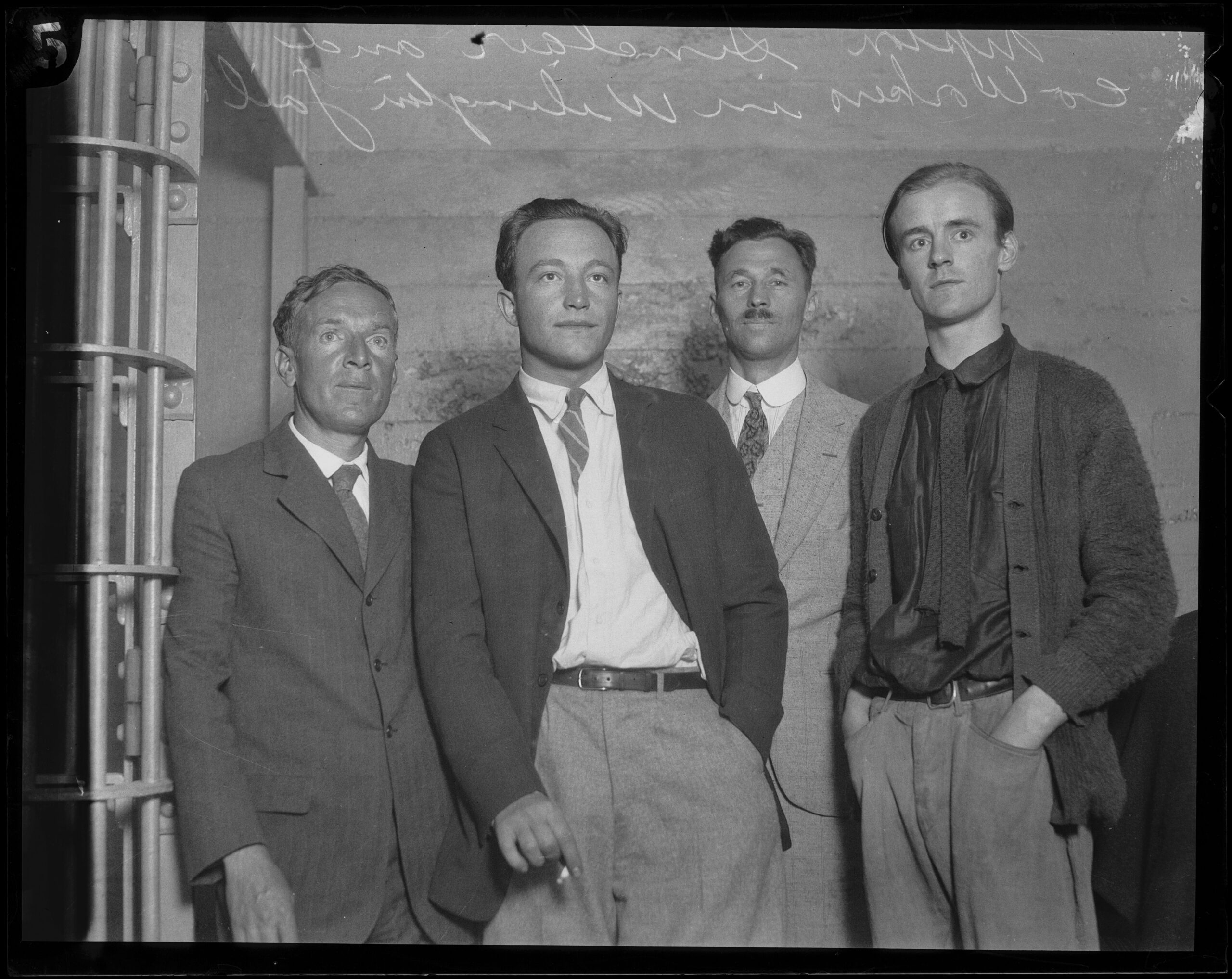

Sinclair met with police chief to protest arrests of striking workers

Sinclair’s desire to concentrate on his writing was interrupted by a strike in 1923 at the San Pedro harbor in Los Angeles led by the Industrial Workers of the World, also known as the Wobblies. Local authorities and members of the American Legion had long opposed the Wobblies and looked down on many of its immigrant members. Considering them to be communists, local authorities used California’s Criminal Syndicalism Law to imprison many of them.

Sinclair responded to their mass arrests by joining with others to meet with the police chief. The police chief, after being told that Sinclair and others intended to speak to union members on private property, aptly named Liberty Hill, reputedly told them to “cut out that Constitution stuff” (Zanger 1969, 391).

Sinclair, three others, arrested for reading the First Amendment

Instead Sinclair and three other men — Hugh Hardyman, Prince Hopkins, and Hunter Kimnbrough — ascended the hill and, in the absence of an audience other than police officers, respectively sought: to read the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution; to read from the Declaration of Independence; to announce that there was no intention to incite a riot; and, even more innocuously, to praise the state’s weather. Police arrested them.

The four men were held incommunicado for some time as the police chief claimed that Sinclair was “‘more dangerous than 4,000 Wobblies’ and ‘the ‘worst radical in the country’” (Zanger 1969, 395). They were thereafter released and the charges against them were dropped.

The Los Angeles Times reported that the city’s mayor George E. Cryer had rejected Sinclair’s attempt for permission to address the strikers by observing that “Too many of the foreigners who come here yap about their constitutional rights and forget their constitutional duties” (Wick 2017).

Sinclair’s arrest led to the founding of California ACLU branch

The publicity generated by Sinclair’s arrest led to the formation of an important branch of the American Civil Liberties Union in Southern California, in which Sinclair, who was friends with ACLU founder Roger Baldwin, took an active role. The event also led to the dismissal of Louis D. Oats as the Los Angeles police chief. It took more than 10 years before the dockworkers secured a contract.

In 1976 a number of philanthropists founded the Liberty Hill Foundation to fight for social justice. In 1997, the city installed an historical landmark to commemorate the Liberty Hill site.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.