In United States v. Stevens, 559 U.S. 460 (2010), the U.S. Supreme Court invalidated a federal law criminalizing the creation, distribution, or possession of images of animal cruelty as substantially overbroad. The Court resisted efforts by the federal government to create a new unprotected category of speech.

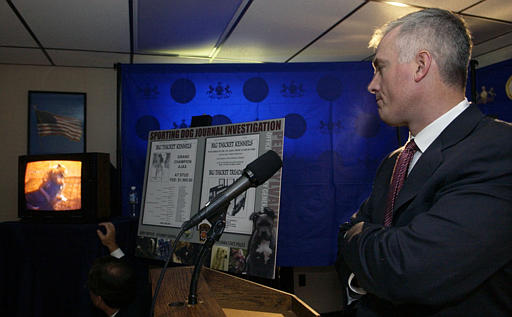

Man who sold videos of fighting pitbulls indicted under federal law prohibiting animal cruelty images

Federal authorities indicted a Pennsylvania-based man named Robert J. Stevens for violating 18 U.S.C. § 48, which prohibits the creation, sale, or possession of images of animal cruelty if done for commercial purposes. Stevens produced and sold videos of pitbulls fighting with each other or mauling other animals.

Stevens moved to dismiss the indictment, claiming the law was facially invalid because of its substantial overbreadth. A federal district court rejected that argument, and a jury convicted Stevens. The district court sentenced him to more than three years imprisonment. However, a divided en banc (full panel) of the Third Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals vacated the sentence, declaring the law facially unconstitutional.

Supreme Court overturns ban on selling animal cruelty images as overly broad

The government appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled 8-1 for Stevens.

Writing for the Court, Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr. explained the odd legislative history of the statute, which was originally designed to address the interstate market of “crush videos” – videos of women in high heels crushing small animals. The measure eventually morphed into a general law against depictions of animal cruelty.

The government had argued that depictions of animal cruelty should fall into an unprotected category of speech, similar to obscenity or child pornography. The government analogized to New York v. Ferber (1982), where the Court had created the unprotected category of child pornography.

Roberts resisted this in strong language, writing: “Our decisions in Ferber and other cases cannot be taken as establishing a freewheeling authority to declare new categories of speech outside the scope of the First Amendment.”

Law could encompass depictions of hunting and animal slaughter, court said

Having rejected the attempt to create a new unprotected category of speech, Roberts then addressed whether the law was substantially overbroad. He found that the law was too broad and could apply to hunting videos and livestock slaughter. He explained that certain types of hunting are lawful in some states and unlawful in others and could lead to prosecutions of individuals for conduct that was legal in certain jurisdictions.

Roberts explained that the market for dogfighting videos was “dwarfed by the market for other depictions, such as hunting magazines and videos.” To Roberts, this was clear evidence that the statute, as currently written, was substantially overbroad. He left open the question of whether a narrowly drawn statute targeting only crush videos or dogfighting videos would pass constitutional muster.

Justice Samuel Alito filed a solitary dissent. He argued that the Court should defer to the government’s interpretation of the law as applying only to crush videos and dogfighting videos. He reasoned that the law “has a substantial core of constitutionally permissible applications.”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2017.