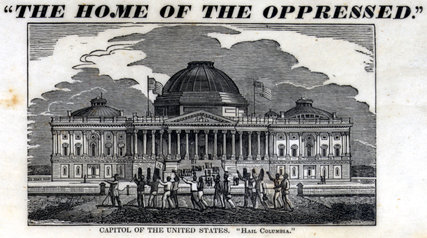

Few issues vexed antebellum America more than the issue of slavery. Unofficially recognized, but not praised, by the use of such circuitous language as “such other persons,” in the U.S. Constitution, the institution contradicted the statement in the Declaration of Independence “that all men are created equal” and equally entitled to the rights of “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

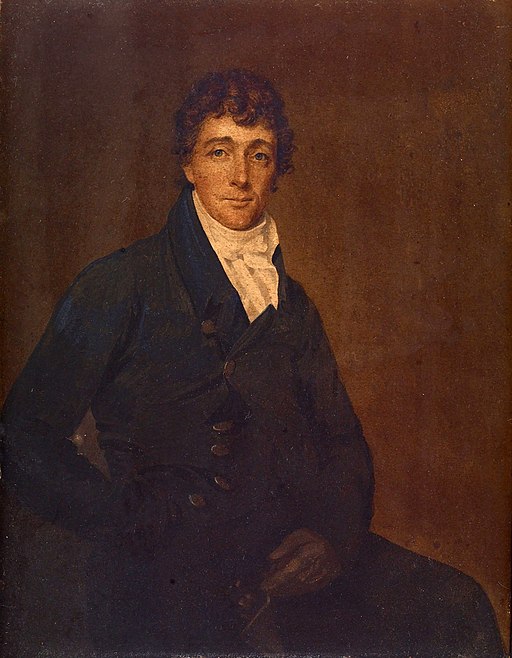

Slavery also contradicted the reference to America as “the land of the free” in “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the song penned by slave-holder Francis Scott Key after the bombardment of Fort McHenry in 1814, which Congress would recognize in 1931 as the national anthem.

The existence of slavery, and of slave markets, in the capital of a nation devoted to such principles were particularly problematic. The city became the site of a number of flashpoints as tensions increased between those who increasingly began to view slavery as an unmitigated evil and those who in time began arguing that the institution (justified by the ideas that whites were superior to blacks) benefited both.

D.C. doctor arrested for possessing abolitionist literature

One such flashpoint occurred in 1835 when Arthur Bowen, an 18-year old slave belonging to an esteemed widow named Anna Thornton, came home after attending a debating society meeting and stood in the door of her bedroom with an axe. Partly with the help of his own mother, who was also in the room with Thornton, Bowen was arrested and taken to jail. Although District Attorney Francis Scott Key was able to muster federal help to secure Bowen’s safety against a mob, his efforts did not stop rioting by white workers and the destruction of the property of black businesses within the city.

The disturbance also led to the arrest of Dr. Reuben Crandall, a Connecticut-born, physician and botanist, at whose establishment a visitor had discovered abolitionist literature with apparent hand-written instructions to “read and circulate.”

Although he had not supported the endeavor and does not appear to have belonged to any anti-slavery societies, Crandall was an object of particular suspicion because his sister had organized a school for African-American children, and he was interrogated in prison amid fears of the mob that had gathered outside. Moreover, at about time of Bowen’s arrest, the city had been deluged with abolitionist literature some of which argued for immediate emancipation, and was thus considered to be highly inflammatory.

Francis Scott Key seeks seditious libel conviction for anti-slavery publications

Key subsequently led a prosecution against Crandall on the grounds of seditious libel.

Key, who was himself a leading member of the American Colonization Society, which sought to solve the slavery problem by sending free blacks abroad, sought to convict Crandall not only on the basis of the contents of what was in the brochure that his visitor had inspected but on the basis of other anti-slavery publications that he kept within a trunk, and which there was no evidence that he had sought to distribute.

Key, a former Federalist who was at the time of the prosecution, a Jacksonian Democrat, sought to prosecute under the standard that the dangerous “tendency” of the material was such as to bring about social disruption. Congress had considered a code for the District of Columbia in 1833 which had provided that:

If any person shall knowingly publish and circulate, or have any agency, directly or indirectly, in publishing and circulating any writing or pamphlet, printed or unprinted, among the free black or slave population of this district, tending to excite a discontented or insurrectionary spirit, such a person, for every such act, upon complaint being made to any justice of the peace within any county or incorporation where such person may be found, shall be arrested under warrant of such justice; and, on proof of the fact, be committed by the justice before whom he may be brought, without bail or mainprize, to the jail of the county or corporation wherein the offense may have been committed, to undergo a trial for the same at the next superior court of law to be holden for the county aforesaid; and, upon conviction thereof, shall be punished by confinement in the penitentiary for not less than two, not more than seven years. (Quoted in Kramer 1980, 130).

It further would have made publication that resulted in actual rebellion a capital offense. According to Neil Kramer, even though the code had not been adopted, it “represented accurately legal practice in the District of Columbia at the time it was compiled,” and was used by the D.C. Circuit Court in this case (1980, 130).

Francis Scott Key was the district attorney in 1835 in Washington D.C. during the arrest of a Connecticut-born doctor who had anti-slavery literature in his office. Dr. Reuben Crandall was put on trial on charges of seditious libel under the claim that abolitionist ideas had a dangerous tendency to disrupt society.

Crandall’s attorney argued for higher standards to prove seditious libel

By contrast, Crandall’s attorneys, Joseph H. Bradley and Richard S. Coxe, emphasized the importance of due process and sought to require higher standards for such a prosecution. At one point, they cleverly read from Key’s own condemnations of slavery, to show that the articles in Crandall’s possession were no more inflammatory than those that Key and members of Congress had used. Crandall’s attorneys were also able to muster a number of positive character references on behalf of their client.

Even though the case was under federal jurisdiction, to which the First Amendment would have applied at the time, as far as the author can ascertain, the case was argued without specific reference by either side to the First Amendment. One of Crandall’s attorneys (Coxe) did reference the Sedition Act of 1798, pointing out that “That statue no longer exists,” and pointing out that “excepting during that short time, and these few cases, no other prosecutions for seditious libels have been instituted, within my knowledge” (The Trial 1836, 51).

He warned that if such proceedings were justified, “seeds will have been sown, which will rapidly vegetate and produce a most abundant harvest” (The Trial 1836, 51). Perhaps indirectly referencing Key’s anthem, Coxe went on to say that:

If upon evidence thus wrested from my possession I shall be indictable, without any overt act, for sedition, and subjected, as this traverser has been, to an incarceration for eight months, preparatory to trial, and then denounced before the community in the unmeasured terms you have applied to him, and be told that for such an offence as having in my private custody, under my own lock and key, publications such as he had, or for loaning one to an intelligent friend for his single perusal, I shall encounter such consequences, then to escape such tyranny would I fly to the remotest parts of this once free land. (Trial, 1836, 52).

Although Crandall’s attorneys secured a not guilty verdict from the jurors, the Circuit Court in Washington had denied him bail, and his health was broken by tuberculosis that he encountered in prison, and he died in early February of 1838. Bowen was sentenced to death, but President Jackson granted him a pardon, and he was sold to another slaveholder outside the District of Columbia (Myers and Musgrove 2017, 80).