The verb to Bowdlerize — to modify written texts to remove offensive language, possibly distorting the material — is taken from the name of Thomas Bowdler (1754–1825), who edited Shakespeare’s plays to ensure that “those words and expressions are omitted which cannot with propriety be read aloud in a family.” Bowdler focused his efforts on revising sexual references and blasphemy.

Bowdler thoroughly edited Shakespeare’s works to make them appropriate for families

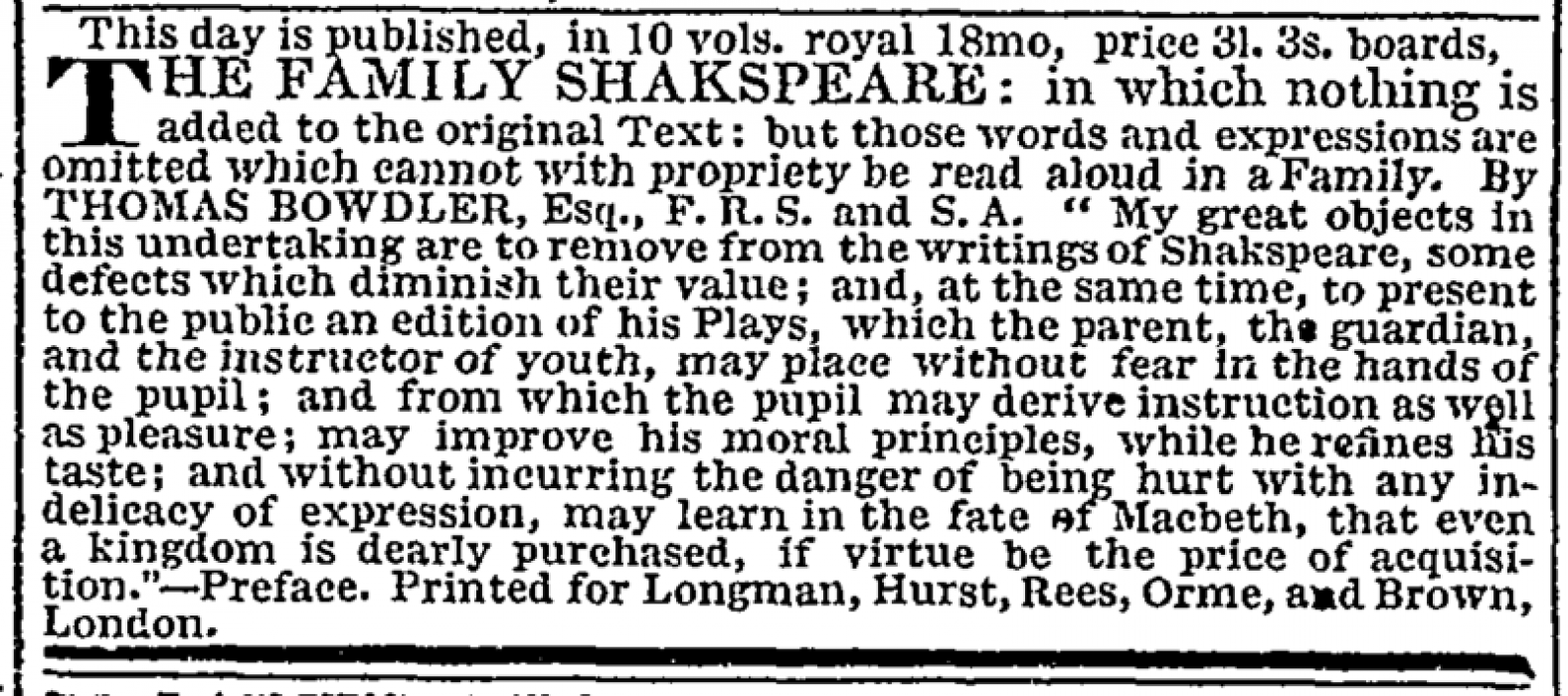

Various 18th century editors published editions of Shakespeare’s work from which they eliminated what they perceived as indelicacies; some even rewrote plays such as King Lear to produce a happy ending. In 1807, however, Bowdler’s The Family Shakespeare set a new standard of thoroughness in policing the morality of the Bard’s plays. The first edition, published anonymously in four volumes, included twenty plays and was largely, if not entirely, the work of Bowdler’s sister Henrietta Maria (“Harriet”) Bowdler (1750–1830). It was not very successful; when Bowdler negotiated for a new edition in 1817, publishers initially responded unenthusiastically.

In 1818 the second edition of The Family Shakespeare was published under Thomas Bowdler’s name, this time in ten volumes containing 36 plays, including reedited versions of the 20 plays of the first edition. After a slow start, the book became a steady seller, with new printings every few years through the 1880s. This success was the result of a dispute in 1821–1822 between Blackwood’s Magazine and the Edinburgh Review, the leading literary journals of the day. When Blackwood’s mocked Bowdler as a peddler of “prudery in pasteboard,” the Edinburgh thanked him for sparing readers from “awkwardness” and “distress.”

Bowdler’s edits took out famous lines

Bowdler’s Othello illustrates his approach. Some of the play’s most famous lines are missing or altered in The Family Shakespeare. Where Iago says of Othello, “ ’twixt my sheets, he has done my office” (1.3.369–370), Bowdler substitutes, “in my bed, he has done me wrong.” Bowdler omits Iago’s effort to inflame Desdemona’s father by telling him, “an old black ram / Is tupping your white ewe” (1.1.88–89). Iago’s similarly goading assertion that “your daughter and the Moor are now making the beast with two backs” (1.1.117–118) becomes “your daughter and the Moor are now together.” Bowdler’s editorial changes contrasted with condensed and forceful imagery elsewhere in the play.

Toward the end of his life, Bowdler also produced a five-volume edition of Gibbon’s Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire featuring “the careful omission of all passages of an irreligious tendency.” The effort was not a success, and the book was never reprinted.

Bowdler referred to in court case

Bowdler is referred to in just one Supreme Court case, Ginsberg v. New York (1968). Justice William O. Douglas, in his dissent, provided a short biographical sketch of anti-obscenity activist Anthony Comstock in which Bowdler is mentioned in a footnote as a “notable forerunner of Comstock” who was “[a]rmed with a talent for discovering the ‘offensive.’ ” Since Douglas’s day, some studios have sought to clean up movies by deleting offensive words and scenes for family viewing.

This article was originally published in 2009. Simon Stern is Professor of Law and English at the University of Toronto. He has published articles and book chapters on obscenity, copyright, criminal procedure, legal fictions, and the history of the common law.