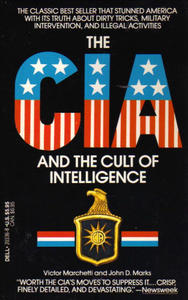

The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, the 1974 book by former Central Intelligence Agency employee Victor Marchetti and former State Department employee John D. Marks, was the first publication to be censored by the U.S. government prior to publication. Legal issues pitted the government’s interest in protecting national security against the right of former government employees and publishers to communicate classified or otherwise sensitive information.

Government stopped Marchetti from publishing secret CIA information

After Marchetti resigned from the CIA in 1969, he began publishing information acquired as a consequence of his work. Marchetti’s actions violated contractual secrecy agreements that he had signed as a condition of employment. In 1972 the U.S. government sought and secured an injunction against his publishing “secret information touching upon the national defense and the conduct of foreign affairs.”

For nearly a year, legal proceedings and injunctions delayed publication of The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence, a critique of the agency’s activities, alleging a preoccupation with covert operations at the expense of intelligence gathering. The government originally ordered 339 deletions of what it termed classified information. After negotiation with Marchetti’s lawyers, the CIA reduced its request to 168 deletions.

Marchetti challenged the government

In United States v. Marchetti (4th Cir. 1972) and Alfred A. Knopf v. Colby (4th Cir. 1975), the government argued that the primary issue centered on a contractual obligation, asserting that Marchetti had agreed to submit his work for prepublication review as a condition of employment. Marchetti claimed a First Amendment right to publish and a “need to know” for the public regarding CIA activities. He contended that enforcement of the secrecy agreement he had signed violated his First Amendment rights and constituted a prior restraint on expression. He also challenged the government’s classification system on the ground that government censors possessed virtually unlimited powers to classify documents and, therefore, to withhold from the public information vital to self-governance. The courts sided with the government.

Courts ruled that national security concerns trump freedom of communication

The issues raised in these proceedings resurfaced in subsequent disputes concerning prepublication agreements in connection with classified information in particular and government secrecy in general in Snepp v. United States (1980), Haig v. Agee (1981), and United States v. Morison (4th Cir. 1988). In all of these cases, the courts ruled that national security concerns trumped the rights of freedom of communication.

This article was originally published in 2009. Richard A. “Tony” Parker is an Emeritus Professor of Speech Communication at Northern Arizona University. He is the editor of Speech on Trial: Communication Perspectives On Landmark Supreme Court Decisions which received the Franklyn S. Haiman Award for Distinguished Scholarship in Freedom of Expression from the National Communication Association in 1994.