In Stewart v. McCoy, 537 U.S. 993 (2002), the Supreme Court granted permission for the defendant, Jerry Dean McCoy, to proceed with his appeal in forma pauperis (as a poor person), but denied the request by the director of the Arizona Department of Corrections, Terry L. Stewart, to obtain a writ of certiorari to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, challenging the defendant’s release from custody.

Federal court overturned conviction for advising street gangs, citing First Amendment rights

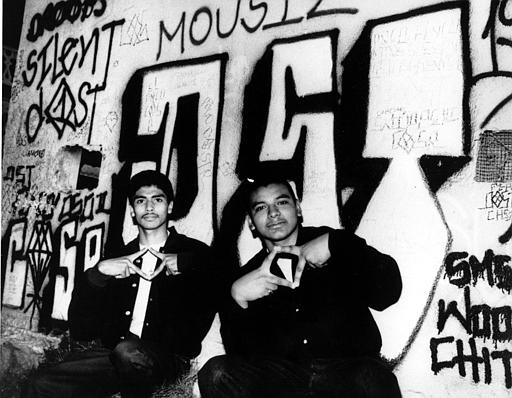

At the outset of the case, an Arizona trial court had sentenced the defendant to fifteen years in prison after it convicted him of advising members of a street gang on how to organize themselves.

His instructions had included advice on beating members of rival gangs. But a district court and federal appellate court overturned his conviction, citing First Amendment free speech rights.

Supreme Court sought to clarify law on incitement to violence

The Supreme Court’s decision is significant because Justice John Paul Stevens filed a statement that sought to clarify the state of law on the incitement to violence since the Court had ruled in Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969) that individuals could be convicted for such incitement only if their speech brought about an imminent threat of lawless action.

Agreeing that McCoy’s penalty had been very harsh, Stevens observed that the appellate court’s conclusion that the “speech ‘was mere abstract advocacy’ that was not constitutionally proscribable because it did not incite ‘imminent’ lawless action” was “surely debatable.”

Referring to Brandenburg, Stevens said, “While the requirement that the consequence be ‘imminent’ is justified with respect to mere advocacy, the same justification does not necessarily adhere to some speech that performs a teaching function.”

Stevens observed that long-range planning of criminal activity could create significant public danger

He further observed: “Long range planning of criminal enterprises — which may include oral advice, training exercises, and perhaps the preparation of written materials — involves speech that should not be glibly characterized as mere ‘advocacy’ and certainly may create significant public danger.”

He found that Brandenburg had “not yet considered whether, and if so to what extent, the First Amendment protects such instructional speech,” and wanted to make it clear that he did not consider the denial of certiorari in the case to “be taken as an endorsement of the reasoning of the Court of Appeals.”

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.