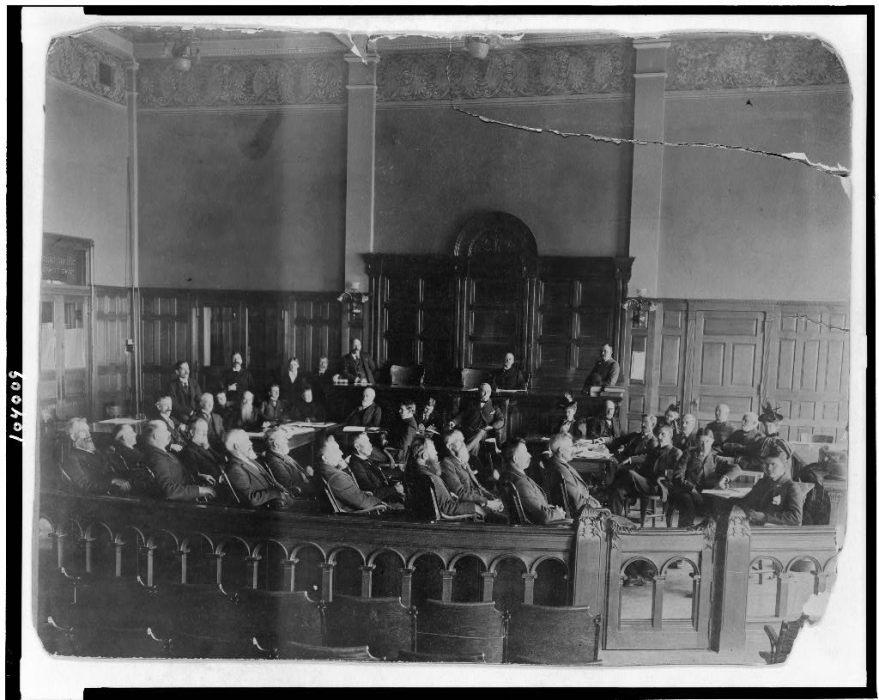

In State v. Willson, 13 S.C.L. (2 McCord) 393 (S.C. App. 1823), an apparent test case, the Constitutional Court of Appeals of South Carolina ruled that the state did not have to exempt the members of a religious group known as the Covenanters from grand jury service.

Religious group opposed participation in government that did not acknowledge God

This group, whose members favored adoption of a Christian amendment — that is, inserting Christian ideas and language into the U.S. Constitution — opposed participation in governments with constitutions that did not specifically acknowledge God. Although at the time the Bill of Rights did not yet apply to the states (the case relied on state law), the case does offer some insights into contemporary understandings of church and state.

Writing on behalf of a unanimous court, Justice Richardson denied that the state was required to extend such an exemption to the Covenanters. He observed that when the legislature made a rule with certain stated exceptions, courts should be wary of further extending such exceptions lest the rule itself be lost amidst them.

Richardson expressed further concern about the court’s inability to separate the sincere from the insincere, citing the example of Judas betraying Jesus. Although Willson had apparently cited some examples of jurors who had in the past been excused for religious beliefs, Richardson observed that such exercises of “generosity” should not provide a pretext for the right of exemption claimed (emphasis in original).

South Carolina judge denied group exemption from jury service

More broadly, Richardson hoped his decision would help reconcile the Covenanters to obeying the law, because all religions agreed “that man is bound to do his duty in whatever situation he may be placed by the God, whom he adores” (emphasis in original), a principle that, Richardson observed, “reconciles even the slave to his master.”

State v. Willson is one of the precedents that provides some basis for ascertaining the degree to which early courts found that the free exercise clause exempted religious individuals from rules of general applicability.

This issue assumed renewed prominence with the Supreme Court decision in Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith (1990), which stated that the free exercise clause required no such exemptions.

This article was originally published in 2009. John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment.