The First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is generally considered the main legal provision protecting expressive freedom.

However, most states had adopted constitutions before the United States did, and most included bills or declarations of rights. Today all of the states have provisions in their constitutions that protect these or similar rights, and in some cases offer greater protection for speech, press, and assembly rights than those based on the U.S. Constitution.

State bills of rights inspired federal constitutional rights

The history and relationship between rights protected under federal and various state constitutions provide important insights into federalism.

The 1776 Virginia Declaration of Rights is often credited with being the source or inspiration for the amendments James Madison offered to the Constitution in 1791. Those (ten) that originally passed came to be known as the Bill of Rights.

Although state bills of rights had inspired the construction of federal constitutional rights, recourse to state constitutions as an independent source of protection for expressive rights was not common until the later 1990s. Instead, because the supremacy clause of the U.S. Constitution takes precedence over state law and constitutions, and because the Warren Court used its powers to incorporate many provisions of the Bill of Rights to apply to the states, there was little incentive or opportunity for state courts to reference their constitutions to protect individual expressive rights.

Justice Brennan encouraged use of state constitutions to protect individual rights

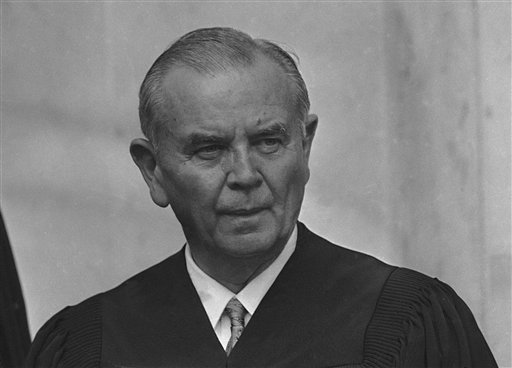

In 1977, sensing that the Supreme Court was retreating from its protection of individual rights, Justice William J. Brennan Jr., pictured here, encouraged state courts to use their state constitutions to protect individual rights independent of federal courts. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

This situation changed in 1977, when Justice William J. Brennan Jr., seeing that the Burger Court was, in his opinion, retrenching on the protection of individual rights, encouraged state courts and judges to use their own constitutions to protect individual rights independently of what the federal courts did vis-à-vis the federal Constitution.

According to the principles of federalism and rules of abstention, if a state court uses its own constitution as the basis of a decision, such as in a case addressing freedom of speech, the U.S. Supreme Court lacks the jurisdiction or authority either to hear or to overturn that decision as long as it meets the federal minimums. Thus, nothing prevents a state court from finding that its own constitution offers more protection for any rights, including expressive rights, in comparison to those found in the U.S. Constitution or Bill of Rights.

In many instances since the late 1970s and early 1980s state courts have used their own constitutions to offer protection to expressive freedoms independently of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment.

State courts differ from Supreme Court on free expression in shopping malls

In some cases, the state courts have also chosen to grant more protection under their constitutions than under the First Amendment. In State v. Henry (1987), the Oregon Supreme Court struck down a state obscenity law as inconsistent based on the broad protection for free expression under the state constitution.

In PruneYard Shopping Center v. Robins (1980), the U.S. Supreme Court held that California could interpret its state constitution to protect political protesters from being evicted from private property, held open to the public, without running afoul of the shopping center owner’s property rights under the Fifth Amendment or speech rights under the First Amendment. In this case, California had gone beyond the federal rule and held that, under the California constitution, a shopping mall owner could not exclude a group of high school students who were engaged in political advocacy.

In New Jersey Coalition Against War in the Middle East v. J.M.B. Realty Corp. (1994), Lloyd Corporation, Ltd. v. Whiffen (1993), and Batchelder v. Allied Stores International, Inc. (1983), however, state courts in New Jersey, Oregon, and Massachusetts reached different conclusions, often granting individuals various rights to gather petition signatures in shopping malls that exceeded those in PruneYard.

On the other hand, in Minnesota v. Wicklund (1999), the Minnesota Supreme Court refused to grant more rights to freedom of expression in shopping malls — in this case, the Mall of America — than found in the PruneYard decision.

New Jesey, Connecticut offer more free expression guarantees than federal constitution

In recent years, the New Jersey Supreme Court has interpreted its state constitutional free-expression guarantee to provide that private homeowner association rules are subject to challenge. The state high court invalidated a homeowner association rule banning all political signs in windows in Mazdabrook Commons Homeowners’ Association v. Khan (N.J. 2012).

In recent years, the New Jersey Supreme Court has interpreted its state constitutional free-expression guarantee to provide that private homeowner association rules are subject to challenge. In this photo, attorney Frank Askin, left, looks on, as attorney Barry S. Goodman addresses the New Jersey Supreme Court in 2007 in Trenton, New Jersey. Askin represented residents who sued an HOA, objecting to a ban on putting political yard signs wherever they want. The state high court invalidated the HOA rule banning all political signs in windows. (AP Photo/Mel Evans, used with permission from the Associated Press)

The Connecticut Supreme Court has interpreted its state freedom of expression guarantee to provide greater free-speech protections to employees than the U.S. Supreme Court provided in Garcetti v. Ceballos (2006).

The state high court reasoned in Trusz v. UBS Realty Investors (2015) that “[t]here is no evidence that the constitutional framers [of the Connecticut Constitution] intended to impose such severe limits on the speech rights of the state’s citizenry.”

New Jersey and Connecticut are more exceptions than the rule.

Most states interpret state constitution protections similar to First Amendment interpretations

Most state high courts continued to interpret their state freedom of expression guarantees similarly, if not identically, to the way the U.S. Supreme Court has interpreted the First Amendment.

Overall, although often ignored, state constitutions provide a rich, independent, and sometimes more expansive protection for expressive freedoms than is found in the First Amendment. Citizens and lawyers generally overlook state constitutional protections, but they too are important clauses defending speech, press, and assembly rights.

This article was originally published in 2009. David Schultz is a professor in the Hamline University Departments of Political Science and Legal Studies, and a visiting professor of law at the University of Minnesota. He is a three-time Fulbright scholar and author/editor of more than 35 books and 200 articles, including several encyclopedias on the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court, and money, politics, and the First Amendment.