Many vice presidents of the United States stay in the background and out of the limelight, but not unlike what he had done for President Dwight Eisenhower, President Richard M. Nixon’s vice president, Spiro T. Agnew, often played the role of an attack dog, mobilizing support for the president with his rhetoric.

Agnew, the son of a Greek immigrant, was an attorney who graduated from Johns Hopkins University and the University of Baltimore who served from 1962 to 1966 as the executive of Baltimore County and then as governor of Maryland from 1967 to 1969.

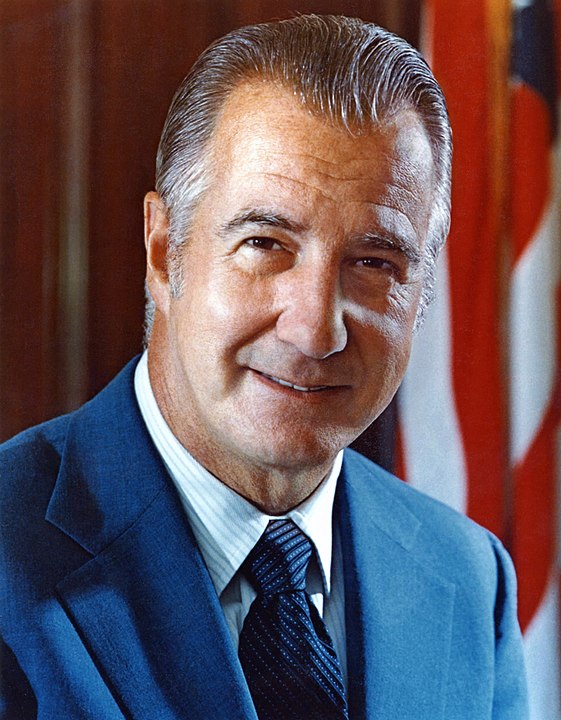

Agnew known for his expressive rhetoric

Nixon and Agnew were elected during a time of great national division over civil rights, the Vietnam War, changing social norms, and student protests. After Nixon chose him as vice president, Agnew quickly earned a reputation for colorful language stressing law and order and disparaging groups that were opposed to the administration.

He referred, for example, to “the nattering nabobs of negativism” who had formed “their own 4-H Club – the ‘hopeless, hysterical hypochondriacs of history.’” He characterized college professors as “an effete corps of impudent snobs who characterize themselves as intellectuals,” and he ridiculed numerous other groups that he associated with the far left.

Agnew’s televised address attacked TV news coverage

Speaking to the Midwest Regional Republican Committee Meeting on Nov. 13, 1969, Agnew became the first sitting vice-president to give a nationally televised address, and he used the occasion to strike out at the media (particularly television), which he thought was biased against administration policies.

In his 1969 speech, which appears to have been largely written by speechwriter and White House assistant Pat Buchanan, Agnew was particularly critical of the way that television commentators had immediately criticized a speech by President Nixon before allowing the American people to come to their own conclusions.

Agnew was speaking at a time when most people got their news from one of three major networks rather than from traditional printed media or from more modern social media. In populist style, Agnew characterized these critics as a “little group of men,” concentrated in Washington, D.C. and New York, who did not represent what Nixon had described as the large silent majority.

Indicating that “I’m not asking for Government censorship or any other kind of censorship,” Agnew suggested that the media was already engaging in censorship of its own. He admonished that “a virtual monopoly of a whole medium of communication is not something that democratic people should blindly ignore.”

He accused the media of portraying the majority of Americans as “embittered radicals” who “feel no regard for their country” and of falsely suggesting that “violence and lawlessness are the rule rather than the exception on the American campus.” In one of his most quoted lines, Agnew indicated that the airways do not “belong to the networks . . . but to the people.”

Agnew also approvingly quoted Justice Byron White’s decision upholding the Federal Communication Commission’s so-called “Fairness Doctrine” mandating equal time for rival political views on electronic media (since overturned) in Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC (1969). There, White had indicated that “It is the right of the viewers and listeners, not the right of the broadcasters, which is paramount.” Agnew added that although he had “raised questions,” he did not have the answers.

Although media leaders were very critical, Agnew received strong public support for his stance.

Others after Agnew have exploited similar press criticisms

The guarantee of freedom of the press in the First Amendment does not, of course, exempt the press from criticism, but Agnew’s speech appears to have created a template for other politicians like George Wallace and Donald J. Trump who regularly attacked the media and cast doubt on the news it conveys.

Moreover, although Agnew’s criticisms stand out, they were actually built in part on earlier liberal and progressive critiques that expressed “concerns about increasing commercialism and concentration in ownership” in the press (Cimaglio 2016, 3) and accused them of being out of touch with the people.

In 1973 Agnew resigned from office (only the second vice president after John C. Calhoun to do so) after pleading no contest to a charge of federal income tax evasion in exchange for the government’s agreement to drop other charges that he had engaged in political corruption while governor of Maryland.

Under the terms of the 25th Amendment, Agnew was replaced by Gerald R. Ford who, in turn, became president after Nixon’s resignation over his ties to the Watergate scandal.

During the presidency of George H. W. Bush, Vice President Dan Quayle attacked the television sitcom Murphy Brown for undermining family values by favorably portraying an unmarried news anchor played by Candice Bergen who was about to give birth and being unsure who the father was. But Quayle's attack on the media was not as far-reaching as that of Donald Trump and others who would follow.

John R. Vile is the dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University and a professor of history. This article was first published Jan. 31, 2024.