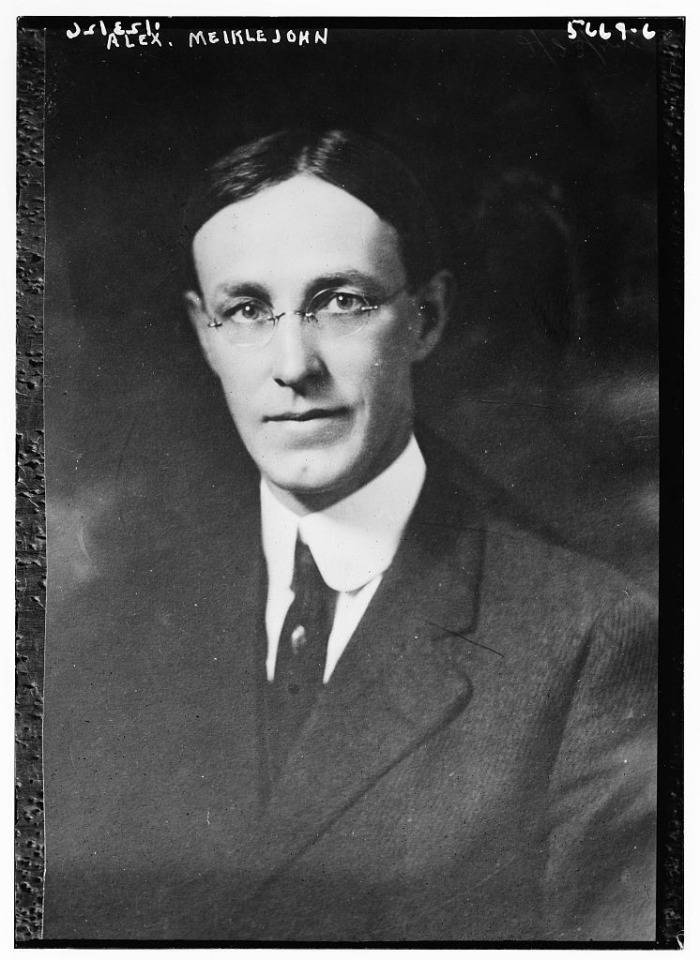

The self-government rationale remains one of the important justifications for freedom of speech. It is often associated with the writings of university administrator and free speech advocate Alexander Meiklejohn, who argued that self-government depends for its survival on a free and robust democratic dialogue.

Self-government rationale ties free speech protections to political speech

Meiklejohn took a Madisonian view of the First Amendment: its protections exist primarily to serve the democratic process.

He called for interpreting the First Amendment’s free speech clause in relation to the larger constitutional focus — the provision and protection of self-government. Because the U.S. constitutional system is one of deliberative democracy, and because the right of free expression plays an indispensable role in the system of public deliberation, he regarded the First Amendment as fostering the kind of deliberative debate required by self-government.

Some scholars say political speech should have preferential treatment over commercial speech

In distinguishing public speech from private speech, Meiklejohn’s theory also gave preferential First Amendment protection to speech that is part of the public arena, and not to speech pursued for private purposes, such as pornography and commercial speech.

Meiklejohn’s instrumentalist view of the First Amendment’s focus on political speech has been adopted by scholars such as Cass R. Sunstein, who advocates a two-tier First Amendment, in which courts would subject restrictions on political speech to the strictest scrutiny, while applying a lower level of scrutiny to nonpolitical speech (Sunstein 1992).

According to Sunstein, as long as there is freedom of political speech, controls on other kinds of speech can always be protested, whereas controls on nonpolitical speech do not possess this uniquely damaging feature.

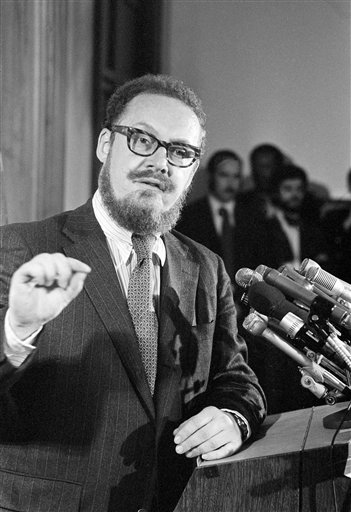

Robert Bork argued for First Amendment focus on political expression over other speech forms

Conservative legal scholar Robert Bork adopted the self-government theory of the First Amendment and argued that the Courts should focus on political expression protection rather than what he thought were less constitutionally grounded categories of expression, like commercial speech. In this 1973 photo, as acting U.S. Attorney General, Bork speaks in a Washington press conference on the Watergate investigation. (AP Photo/Henry Burroughs, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Judge and conservative legal scholar Robert H. Bork also adopted Meiklejohn’s self-government theory. He argued that courts must focus the First Amendment on political expression to avoid the judicial activism that protecting any less constitutionally grounded categories of expression would entail.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized the importance of political speech and the self-government rationale.

- In Buckley v. Valeo (1976), the Court stated that the First Amendment extends the broadest protection to such political expression.

- In Burson v. Freeman (1992), the Court pointed to the “practically universal agreement that a major purpose of [the First] Amendment [is] to protect the free discussion of governmental affairs.”

- In Federal Communications Commission v. League of Women Voters of California (1984), the Court recognized that “expression on public issues has always rested on the highest rung of the hierarchy of First Amendment values.”

New York Times v. Sullivan created higher protection for political speech

Despite these statements, the Court has never specifically ruled that to qualify for the highest levels of constitutional protection the speech at issue must relate to self-government. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Court did, in an attempt to protect political speech, create a higher bar — the actual malice standard — for public officials seeking to collect libel judgments than for ordinary citizens.

This article was originally published in 2009. Patrick Garry, JD, PhD, is a professor of law at the University of South Dakota School of Law. Professor Garry’s books on the First Amendment include Scrambling For Protection: The New Media and the First Amendment, An American Paradox: Censorship in a Nation of Free Speech, and Limited Government and the Bill of Rights.