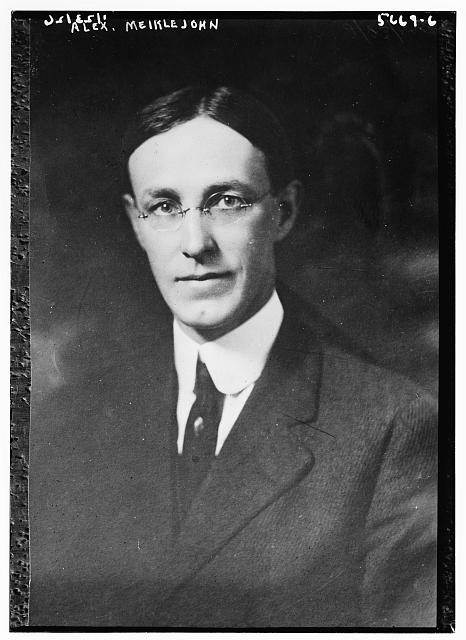

The philosopher Alexander Meiklejohn (1872–1964), a passionate advocate for free speech, wrote extensively on both educational theory and the First Amendment.

Meiklejohn said First Amendment’s allowed debate in order to make informed choices

He argued that the First Amendment’s primary purpose is to ensure that voters are free to engage in uninhibited debate and discussion in order to make informed choices about their self-government. His theories were influential in his time and are still widely discussed today.

Born in England, Meiklejohn moved with his family to Rhode Island when he was a child. After earning two degrees from Brown University, he received a Ph.D. in philosophy from Cornell in 1897. He was hired as a philosophy teacher at Brown and in 1901 was named dean of the university. He served as president of Amherst College from 1913 to 1924. He then founded an experimental college at the University of Wisconsin, where he was a professor, and in 1938 moved to the San Francisco School of Social Studies.

Meiklejohn also served for many years on the national committee of the American Civil Liberties Union. In 1963 he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

Meiklejohn said self-governance is the justification for free speech

The core of Meiklejohn’s understanding of the First Amendment is that a commitment to self-governance is the bedrock principle that justifies freedom of speech.

As he wrote in “The First Amendment Is an Absolute” (Supreme Court Review [1961]), Meiklejohn believed that the “revolutionary intent of the First Amendment” was to “deny to all subordinate agencies,” such as Congress or the president, any “authority to abridge the freedom of the electoral power of the people.”

In “What Does the First Amendment Mean” (University of Chicago Law Review 20 [Spring 1953]), he explained further that the First Amendment guarantees the political freedom of the people of the United States by ensuring that they are presented with open discussions of all issues, even from unpopular viewpoints. The value in free speech, therefore, is that it produces informed voters.

Critics say focus on promoting democracy undervalued non-political expression

Critics believe that Meiklejohn’s focus on the role of the First Amendment in promoting democracy undervalues speech and expression that is unrelated to politics.

Meiklejohn argued that speech that was related to self-government was protected by the First Amendment, while private expressions that did not deal with matters of public concern were protected only by the Fifth Amendment’s due process clause.

Critics argue that such a division is unjustified by the text of the Constitution and that such an understanding fails to protect art or other forms of self-expression. Meiklejohn attempted to counter such criticism by arguing that voters are informed by an extremely wide range of expressions, including literature and the arts.

This article was originally published in 2009. Professor Dara E. Purvis is a scholar of family law, contracts, feminist legal theory, and sexuality and the law. She is particularly interested in the intersection between gender stereotypes and the law. Her work examines gendered impacts of the law and proposes neutralizing reforms, most recently in the context of how the law defines parenthood.