The Northwest Ordinance (formally the Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North West of the River Ohio) primarily created the Northwest Territory. The ordinance was passed by the unicameral Congress of the Articles of Confederation on July 13, 1787, and affirmed, with slight modifications, by the U.S. bicameral Congress on August 7, 1789. Provisions of the Northwest Ordinance presaged several provisions of the Constitution and the First Amendment and announced a prohibition of slavery in the states to be formed out of the territories, albeit with an accompanying fugitive slave clause.

Northwest Ordinance organized territory to become states

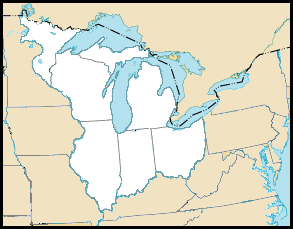

When the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolutionary War in 1783, the United States laid claim to lands stretching from the Ohio River west to the Mississippi and north to the Great Lakes. This land, which came to be known as the Northwest Territory and which had long been inhabited by Native Americans, had been claimed by several states. The states gave up their claims when they ratified the Articles of Confederation.

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson proposed a plan for developing the new territory into states. The main features of that plan were adopted by the Continental Congress in 1787 while the Constitutional Convention was meeting in Philadelphia and were incorporated into Article IV, Section 3 of the new Constitution. This plan for accepting new states into the Union applied not only to the Northwest Territory but also to the Louisiana Territory that the U.S. acquired from France in 1803 and other territories. Whereas all slaves were prohibited in the Northwest Territory, the United States later allowed slavery in Missouri and in the territories south of 36°30.’

The primary purpose of the ordinance was to terminate the claims of individual states and to organize the territory into entities that could become new states so that they would not remain in an unequal relationship like the 13 colonies had once been in Great Britain. These purposes are accomplished by Sections 1 through 13 of the document. Section 14 announced a perpetual compact between the people of the original states and the people of the new territories that could be altered only by mutual consent.

Ordinance promised religious toleration and other rights

In setting the stage for the Constitution, the first article of the compact, which resembles the free exercise clause of the First Amendment, promised religious toleration for any person “demeaning himself in a peaceable and orderly manner” regardless of that person’s mode of worship or religious sentiment.

The second article announced a series of rights related to criminal procedure, political equality and the protection of private property, which reflected protections in state bills of right and, in turn, overlapped with similar provisions that were later incorporated in the Bill of Rights. In similar fashion, when the U.S. later acquired foreign territories, it specified that certain rights would apply there.

The third article announced that schools and means of education were to be encouraged, because “religion, morality, and knowledge” were necessary to “good government and the happiness of mankind.”

After the Civil War in the 1860s, the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, Northwest Ordinance, and Constitution, taken together, came to be called the “Organic Laws of the United States of America.” The title conveys the conviction, enunciated by President Abraham Lincoln, that the founding of the United States was “dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.”

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in January 2024 by John R. Vile. Paul J. Cornish is an associate professor of political science at Grand Valley State University. He has published articles on the political thought of John Adams, and on the concepts of natural rights, toleration, and constitutional government in the Catholic natural law tradition