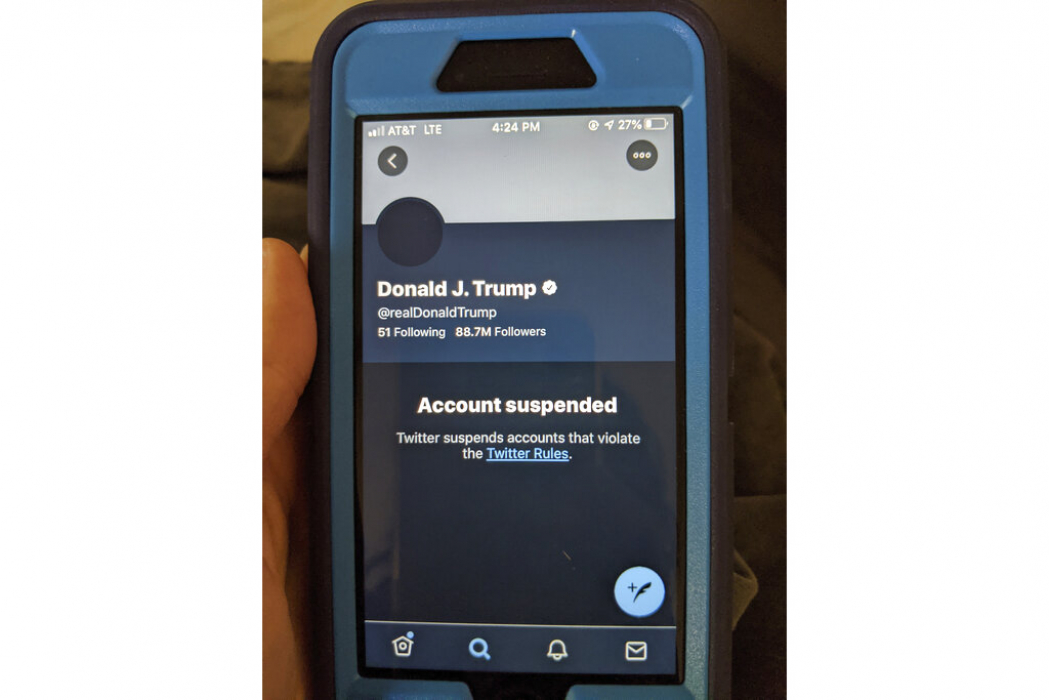

In 2021, the state of Florida enacted the “Stop Social Media Censorship Act” barring social media companies from removing political candidates from their service, prioritizing or deprioritizing posts by or about candidates and removing anything posted by a “journalistic enterprise” based on content.

The law faced an immediate legal challenge by social media companies that said the law violated the First Amendment by limiting their content-moderation activities and forcing disclosures of how they make such decisions.

A district court issued an injunction, stopping the law from going into effect. The 11th U.S. Court of Appeals in May 2022 in NetChoice v. Attorney General of Florida upheld most of that injunction, concluding that much of the law likely violated the free speech rights of private companies.

“The question at the core of this appeal is whether the Facebooks and Twitters of the world —indisputably ‘private actors’ with First Amendment rights — are engaged in constitutionally protected expressive activity when they moderate and curate the content that they disseminate on their platforms. The State of Florida insists that they aren’t, and it has enacted a first-of-its-kind law to combat what some of its proponents perceive to be a concerted effort by ‘the ‘big tech’ oligarchs in Silicon Valley’ to ‘silenc[e]’ ‘conservative’ speech in favor of a ‘radical leftist’ agenda,” the 11th Circuit Court said in its ruling.

“We hold that it is substantially likely that social-media companies — even the biggest ones —are ‘private actors’ whose rights the First Amendment protects… that their so-called ‘content-moderation’ decisions constitute protected exercises of editorial judgment, and that the provisions of the new Florida law that restrict large platforms’ ability to engage in content moderation unconstitutionally burden that prerogative.”

Quoting a 2019 Supreme Court opinion in Manhattan Community Access Corp. V. Halleck, the 11th Circuit said “‘Whatever the challenges of applying the Constitution to ever-advancing technology, the basic principles of freedom of speech and the press, like the First Amendment’s command, do not vary when a new and different medium for communication appears.

“One of those ‘basic principles’—indeed, the most basic of the basic—is that ‘[t]he Free Speech Clause of the First Amendment constrains governmental actors and protects private actors.’ Put simply, with minor exceptions, the government can’t tell a private person or entity what to say or how to say it.”

A few months after the 11th Circuit’s ruling, the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals adopted an opposite logic regarding a similar Texas law that barred social media companies from censoring content based on the user’s viewpoint. The 5th Circuit found ample legal room to regulate private companies to prevent discrimination based on viewpoint and overturned an injunction that had prevented the law from going into effect.

Both decisions have been appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court, which has not yet accepted or denied review.

11th Circuit: Social media companies have First Amendment rights to curate content

The 11th Circuit held that social media companies are private enterprises with First Amendment rights when they moderate and curate the content disseminated on their platforms.

This happens when the companies remove posts that violate terms of service and choose how to prioritize and display posts, selecting which users’ speech viewers will see and in what order.

“(W)hile the Constitution protects citizens from governmental efforts to restrict their access to social media, no one has a vested right to force a platform to allow her to contribute to or consume social-media content.”

The 11th Circuit cited the U.S. Supreme Court opinion in Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974) in which the Court held that a newspaper’s decisions about what content to publish and its “treatment of public issues and public officials — whether fair or unfair — constitute the exercise of editorial control and judgment” that the First Amendment was designed to safeguard.

In that case, Florida had passed a law requiring any newspaper that ran an article critical of a political candidate to give the candidate equal space in its pages to reply.

The Court concluded in Miami Herald that the state’s attempt to compel the newspaper to “publish that which reason tells them should not be published is unconstitutional” and an “intrusion into the function of editors.”

Later, the U.S. Supreme Court extended the rationale beyond the protection of the editorial judgment of newspapers, applying it to a utility company that was being forced by a state agency to include in its billing envelopes speech of a third party with which the company disagreed.

And in Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian & Bisexual Group of Boston, the Supreme Court used the same reasoning in concluding that because a parade constitutes protected expressive conduct, the parade sponsors cannot be forced under a nondiscrimination statute to allow a gay-pride group to march.

“Social-media platforms exercise editorial judgment that is inherently expressive (conduct),” the 11th Circuit said. “When platforms choose to remove users or posts, deprioritize content in viewers’ feeds or search results, or sanction breaches of their community standards, they engage in First-Amendment-protected activity.”

The 11th Circuit rejected the state’s arguments that because the vast majority of content that makes it onto a social media platform never gets reviewed, the companies are engaged in conduct that is insufficiently expressive to warrant First Amendment protection.

Florida pointed to other Supreme Court rulings that required private entities to “host” other speech, including a shopping center that did not want to allow members of the public to distribute petitions on its property and a law school that did not want to allow military recruiters. The 11th Circuit rejected both arguments as not relevant to the social media companies which it distinguished as being in the business of disseminating curated collections of speech.

11th Circuit: Social media companies not common carriers

The 11th Circuit also rejected “the crux of the State’s position” expressed during oral arguments that “there are certain services that society determines people shouldn’t be required to do without,” and that this is “true of social media in the 21st century.”

Under this argument, Florida would treat social media companies as “common carriers,” which, like phone companies and railroads, can be regulated and required to refrain from discriminatory practices in determining who can use their services.

The 11th Circuit viewed social-media companies more like cable operators, which retain their First Amendment right to exercise editorial discretion on what channels they carry, rather than traditional common carriers.

The court also observed that Congress distinguished internet companies from common carriers in the Telecommunications Act of 1996, which states that “(n)othing in this section shall be construed to treat interactive computer services as common carriers or telecommunications carriers.”

Further, the court said that the state cannot strip a private company of its First Amendment rights simply by labeling it as a common carrier.

Court says it’s not government’s job to prevent ‘unfair’ speech

Even if the Florida law did not trigger the “strict scrutiny” standard of review, the 11th Circuit said it likely would not hold up under “intermediate scrutiny” because it is not narrowly tailored to achieve a specific government interest.

“Put simply, there’s no legitimate — let alone substantial — government interest in leveling the expressive playing field,” the court said. “At the end of the day, preventing ‘unfairness’ to certain users or points of view isn’t a substantial government interest; rather, private actors have a First Amendment right to be ‘unfair’ — which is to say, a right to have and express their own points of view.”

Court: Disclosure to provide rationale of every content decision is overly burdensome

The 11th Circuit also examined the disclosure requirements of the law, including a requirement that the platforms provide notice and a detailed justification for every content-moderation action.

The court said that this provision is substantially likely to be unconstitutional under the First Amendment because “it is unduly burdensome and likely to chill platforms’ protected speech.”

It noted that YouTube alone removed more than a billion comments in a single quarter of 2021 and a law requiring written notice and a “thorough rationale” for each of those decisions poses significant implementation costs and exposes the social media platforms to massive liability — up to $100,000 in statutory damages per claim.

However, the court ruled that other disclosure requirements in the law, including those that require the platforms to publish their standards, inform users about rule changes, provide users with view counts for their posts and inform candidates about free advertising, were purely factual and uncontroversial and did not have the same problems.

This article was published in April 2023. Fisher is director of the Seigenthaler Chair of Excellence in First Amendment Studies, director of Tennessee Coalition for Open Government and a former journalist.