In the landmark decision in Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697 (1931), the Supreme Court fashioned the First Amendment doctrine opposing prior restraint and reaffirmed the emerging view that the Fourteenth Amendment incorporated the First Amendment to the states.

The decision is considered one of the pillars of American press freedom.

Jay Near was the muckraking editor of The Saturday Press. In fall 1927, Near published a series of articles attacking several Minneapolis city officials for dereliction of duty.

The Near Court summarized The Saturday Press accusations as charging, “… in substance, that a Jewish gangster was in control of gambling, bootlegging, and racketeering in Minneapolis, and that law enforcing officers and agencies were not energetically performing their duties.”

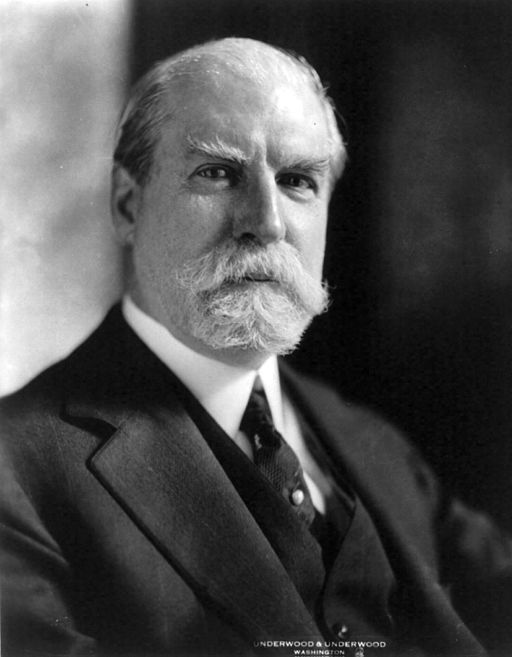

Floyd B. Olson, then the county attorney for Hennepin County, filed a restraining order against the muckracking tabloid, The Saturday Press, in Minneapolis, using a public nuisance law that said the state could shut down “a malicious, scandalous, and defamatory newspaper, magazine, or other periodical.” The Supreme Court overturned the action as unconsitutional prior restraint. Olson later became Minnesota’s governor. (Portrait of Olson as governor, public domain)

One of the targeted law enforcement officers was Floyd B. Olson, the Hennepin county attorney at the time and future Minnesota governor. He filed an action to enjoin publication of The Saturday Press permanently as “malicious, scandalous and defamatory.” A state court enjoined further publication of The Saturday Press under the Minnesota Public Nuisance Law.

Government cannot restrain the press from publishing, Supreme Court says

The Supreme Court reversed, 5-4.

Writing for the majority, Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes began by affirming: “It is no longer open to doubt that the liberty of the press and of speech is within the liberty safeguarded by the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment from invasion by state action.”

Hughes then recast William Blackstone’s famous definition of press freedom in First Amendment terms. In his Commentaries on the Laws of England (1765–1769), Blackstone had defined “liberty of the press” as consisting of “laying no prior restraints upon publications.” Referring to the Minnesota Public Nuisance Law, Chief Justice Hughes observed that the law was “the essence of censorship.”

Justice Charles Evans Hughes wrote that imposing prior restraints upon publications relating to public officers is counter to a “deep-seated conviction that such restraints would violate constitutional right.”

Understood in these terms, the permanent injunction of The Saturday Press runs counter to the conception of liberty deeply embedded in Anglo-American jurisprudence:

“The fact that for approximately 150 years there has been almost an entire absence of attempts to impose previous restraints upon publications relating to the malfeasance of public officers is significant of the deep-seated conviction that such restraints would violate constitutional right.”

Although individuals could sue Near for libelous remarks, the government did not have the power to bar publication of his writings in advance. This would constitute an impermissible prior restraint on expression.

Split decision includes four justices who dissented about meaning of press liberty

Justice Pierce Butler and three other dissenters rejected both the Near majority’s view of the First Amendment’s applicability to the states and its interpretation of the First Amendment.

“The decision of the Court,” Butler argued, “declares Minnesota and every other state powerless to restrain by injunction the business of publishing and circulating among the people malicious, scandalous, and defamatory periodicals that … [have] been adjudged … a public nuisance. It gives to freedom of the press a meaning and a scope not heretofore recognized and construes ‘liberty’ in the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to put upon the states a federal restriction that is without precedent.

This article was originally published in 2009. James C. Foster is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Oregon State University-Cascades.