In Mills v. Alabama, 384 U.S. 214 (1966), the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the Alabama Supreme Court to conclude that a state law placing criminal liability on an election day newspaper editorial violated the First Amendment.

Editor arrested for running an election editorial on election day

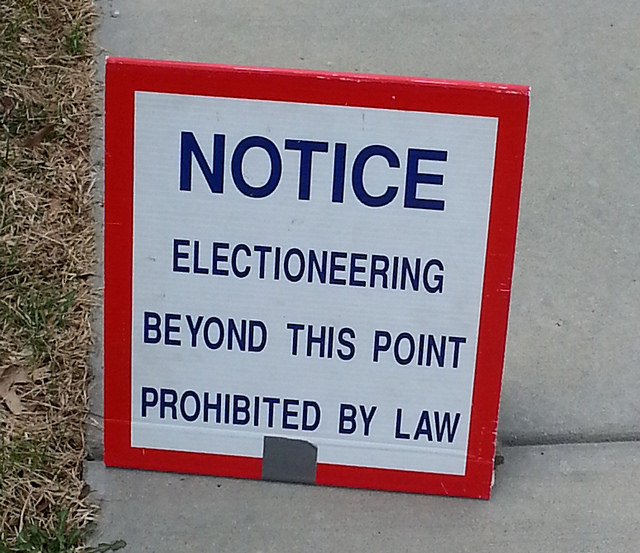

In November 1962, the Birmingham Post-Herald ran an editorial on election day castigating the city government and urging readers to vote for a city initiative to establish “mayor-council” government in Birmingham. The newspaper’s editor, James E. Mills, was arrested and charged with violating Alabama’s Corrupt Practices Act. That law made it a crime “to do any electioneering or to solicit any votes … in support of or in opposition to any proposition that is being voted on on the day on which the election … is being held. ”

The trial court held that the law was unconstitutional, but the Alabama Supreme Court reversed and remanded the case for a trial, stating that the act as applied to this case was “clear, unambiguous and not an unreasonable limitation upon free speech, which includes free press.”

State thought that the case was not appealable

When Mills appealed his case to the U.S. Supreme Court, the state moved to dismiss the appeal on the grounds the Alabama Supreme Court’s judgment was not a “final” one, and therefore was not appealable under federal law.

Justice Hugo L. Black, writing for the Supreme Court, found that the case presented a “final judgment” as required by 28 U.S.C. section 1257, even though the Alabama Supreme Court had remanded the matter for further proceedings. The Alabama court had clearly directed the trial court to find the defendant guilty. Waiting for a trial, noted Black, would not only impose “an inexcusable delay of the benefits Congress intended to grant by providing for appeal to this Court,” but also result in an “unnecessary waste of time and energy in judicial systems already troubled by delays.”

Justice John Marshall Harlan II, writing separately, believed the case was not a final state judgment and that the Court lacked jurisdiction.

Court held that the prohibition against election day editorials violated the First Amendment

On the merits, the Court held that the prohibition against election day editorials or other forms of “electioneering” violated the First Amendment. Although states have the power to regulate conduct in and around polling places to maintain order, the Alabama law unconstitutionally impinged on the free discussion of political affairs. Black’s opinion noted this restriction was especially egregious when imposed upon the press because of its “important role in the discussion of public affairs.” He noted: “Suppression of the right of the press to praise or criticize governmental agents … muzzles one of the very agencies the Framers of our Constitution thoughtfully and deliberately selected to improve our society and keep it free.”

Justice William O. Douglas, joined by Justice William J. Brennan Jr., concurred, concluding that jurisdiction was proper and that the law violated the Constitution, albeit without the same emphasis on the special role of the “press” reflected in the majority opinion.

Court cited Mills to show special press role

Several decades later, the Court’s evocation of a special “press” role reemerged in Austin v. Michigan Chamber of Commerce (1990). There, Justice Thurgood Marshall, writing for the majority, cited Mills in upholding state limits on corporate political activity. In Austin, the state law under scrutiny contained a “press exemption” and survived scrutiny. Yet in cases such as Dun and Bradstreet, Inc. v. Green Moss Builders, Inc. (1985), the Court has held that the press does not enjoy any preferred constitutional status.

Allison Hayward is an elections and ethics attorney in California. She serves on the board of the Office of Congressional Ethics and on the California Fair Political Practices Commission. This article was originally published in 2009.