Article I, Section 2, Clause 3, of the U.S. Constitution provides that states shall be represented in the U.S. House of Representatives according to population, which shall be determined by a census held every 10 years. Although the Constitution does not mandate that states be divided into separate districts to elect members of the House, this has been the practice through most of U.S. history.

Section 2 of the 14th Amendment emphasizes that state apportionment in the House of Representatives shall be based on population and (in an unenforced provision) even provides for reduced representation for states that deny the vote to its citizens.

Legislative apportionment and gerrymandering

As a republican, or representative, democracy, fair representation is equally important at the state level. Although the U.S. Supreme Court once considered such issues to be political questions for the elected branches to resolve, it decided that such issues were justiciable in Baker v. Carr (1962). It subsequently used the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment to apply the “one-person, one-vote” standard to congressional districts in Wesberry v. Sanders (1964) and to both houses of bicameral state legislatures in Reynolds v. Sims (1964) and other cases. These cases required that districts must be relatively equal in population.

Early Americans were familiar with the practice of gerrymandering (named after Elbridge Gerry, an American Founding Father) whereby legislators would draw boundaries to favor their parties or other interests. They can do this either by packing voters of one party together in a district or districts where excess party votes are “wasted” or by cracking such concentrations of party members and dividing them into districts where they are outnumbered by members of the other party. From time to time, the Supreme Court has intervened, as in Gomillion v. Lightfoot (1960), to prohibit racial gerrymandering to exclude Black voters, but in Rucho v. Common Cause (2019), the Court refused to intervene in cases of partisan gerrymandering, which often overlaps with racial gerrymandering.

Redistricting argument based on First Amendment

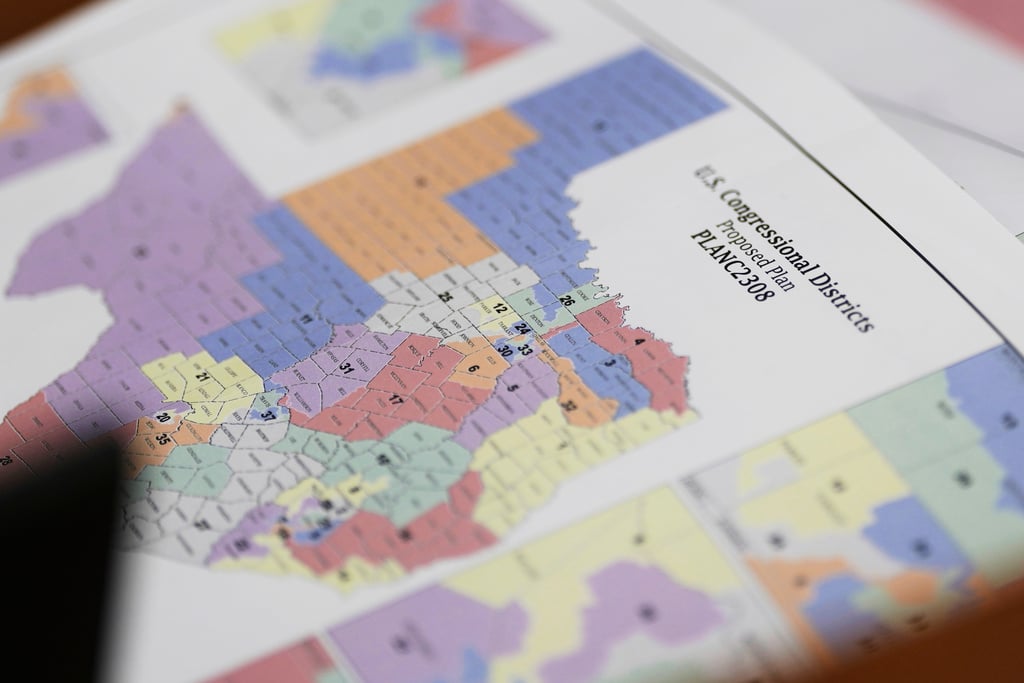

Particularly as computer programs make gerrymandering easier for those who seek party advantage, partisanship has increased, and the balance between Democrats and Republicans within the U.S. House of Representatives is nearly even, political parties have pressured states to increase their partisan representation through gerrymandering congressional districts. In 2025, Governor Greg Abbott of Texas called the state legislature to session for a mid-10-year census and redistricting, which might be the basis for giving Republicans as many as five new seats in Congress. Some Democrat governors threatened to respond in kind by gerrymandering their own states.

Most challenges to malapportionment are based almost exclusively on the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment and judicial precedents emphasizing its importance. However, a brief filed by professors of election and constitutional law on behalf of plaintiffs in Gill v. Whitford (2017), which questioned partisan apportionment in Wisconsin but was eventually rejected on the basis that the plaintiffs lacked standing, relied heavily on First Amendment rights of association in making their case.

The professors argued that “the right to freedom of association, which is associated with the First Amendment right of peaceable assembly, does more than just safeguard the right to join a political party or other group of like-minded people. It also prohibits state regulations that discriminatorily burden a political group’s ability to influence the electoral process.”

The professors classified such partisan gerrymandering as a form of content and viewpoint discrimination, which they argued was particularly suspect when it involved, as participation in parties does, political speech. The professors further suggested that the courts should focus on an “efficiency gap,” representing the difference between the percentage of state-wide party affiliation and party representation within a state legislature. They believed that an efficiency gap, like that in Wisconsin, in which representation of one party by 10% or more in the legislature than state partisan identification, should be subject to strict scrutiny that a state could only justify with a compelling interest, which they did not think was present in this case.

Future prospects

The current Supreme Court does not seem inclined to intervene in state apportionment matters. Should it change direction in the future, the argument connecting fair apportionment to First Amendment associational rights could well supplement arguments from the equal protection clause.

John R. Vile is a political science professor and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University.