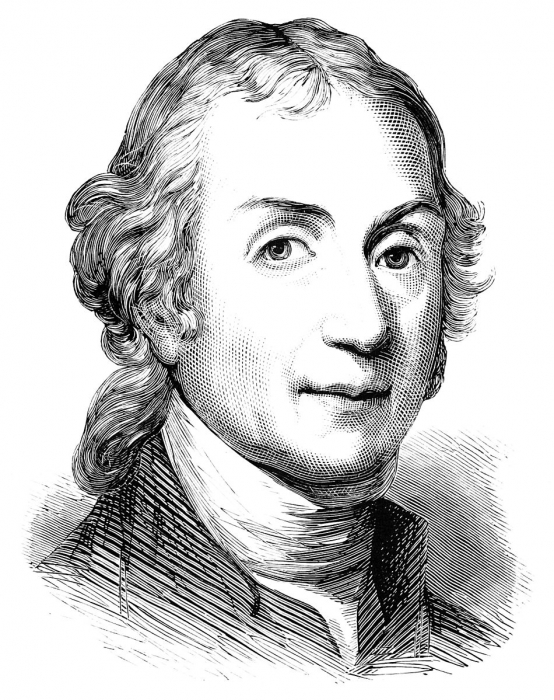

Joseph Priestley (1733–1804), a nonconformist English minister, scientist, and political theorist, wrote prolifically and was a notable figure of the eighteenth-century Enlightenment. In the second half of the eighteenth century, a group of British scholars and writers began to challenge the governmental and religious settlement that had arisen out of England’s “Glorious Revolution” of 1689. These reformers protested the limited nature of representation and the principle of religious uniformity within the British system. Priestley became a leading figure among these thinkers, who came to be called the friends of America, and his writings had a major influence on the First Amendment principles of religious liberty in the U.S. Constitution.

Priestley was a scientist and writer on representative government

Born in West Yorkshire, England, Priestley was educated at the Daventry Academy. At various times he was employed as a minister and schoolmaster, while at the same time conducting laboratory experiments. The discoverer of oxygen, he published more than 150 books during his lifetime. His most important political writings included Essay on the First Principles of Government (1768) and Letters to Burke: A Political Dialogue on the General Principles of Government (1791), which was a vindication of the French Revolution against the arguments of Edmund Burke.

In his Essay on First Principles Priestley carefully distinguished between political liberty and civil liberty. Political liberty involves one’s power to hold public office, or at least to vote in the nomination of those who will hold office. Civil liberty is one’s power over one’s own actions in those areas in which the government must not infringe.The great value of political liberty for Priestley was that it was the only sure guarantee of civil liberty for the members of the state. From this idea he developed a theory of representative government that went far beyond the narrow representative system that existed in the parliamentary government of the eighteenth century.

Priestly wrote in support of relgious toleration

Priestley wrote extensively on religion and in support of religious toleration. He defended the rights of Protestant dissenters and Roman Catholics against the Church of England and the Thirty-Nine Articles of Religion that individuals were required to subscribe to in order to hold various public offices in England. Priestley’s approach to religious toleration went far beyond the framework set by John Locke, in the previous century, in that it derived an unconditional toleration of religious opinion from the natural right to freedom of conscience. As a consequence, even atheists were entitled to toleration. Priestley also sought the end of religious establishment, arguing that the only connection between the church and the state should be in their advocacy for common principles and policies within their own proper spheres of activity.

Priestley moved to America and had an impact on the development of the First Amendment

In the early stages of the French Revolution, Priestley was subject to increasingly hostile verbal attacks because of his support for the republican cause. Finally, in 1791, a riot broke out that resulted in the destruction of his laboratory. Priestley and his family immigrated to the United States in 1794, where he was treated with great respect as a man of learning and supporter of the American cause. Priestley and others, such as Richard Price, James Burgh, and John Cartwright, had a profound impact on the development of the First Amendment and the principles of religious freedom that developed in the United States. Their views are a frequent topic in the letters exchanged by Thomas Jefferson and John Adams in the early nineteenth century and more closely approximate the principles of the First Amendment than do those of more famous figures such as Locke.

This article was originally published in 2009. Paul J. Cornish is Associate Professor of Political Science at Grand Valley State University. He has published articles on the political thought of John Adams, and on the concepts of natural rights, toleration, and constitutional government in the Catholic natural law tradition