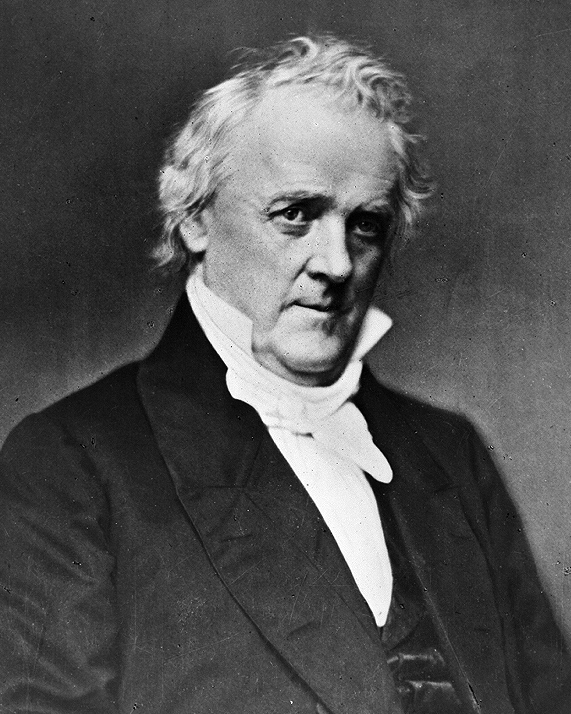

James Buchanan (1791-1868), who was born in Pennsylvania and earned his bachelor’s degree at Dickinson College, had a distinguished career as a lawyer, politician and diplomat before succeeding Franklin Pierce to become the 15th U.S. president, serving from 1857 to 1861.

Abraham Lincoln followed Buchanan as president. Prior to his presidency, Buchanan had served in the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, in the U.S. House of Representatives, as a minister to France, as a U.S. senator from Pennsylvania, as Secretary of State under James K. Polk, and as the minister to the United Kingdom under President Pierce.

Buchanan, a Democrat, accepted the notion that each incoming state should be able to decide whether it would be slave or free (the idea of popular sovereignty, which Lincoln and the Republican Party opposed). He supported the landmark U.S. Supreme Court Dred Scott Decision of 1857 that overturned the Missouri Compromise, which had drawn a line between free and slave territories, and declared that people of black African descent were not and could not be citizens of the United States.

In his inaugural address, Buchanan praised immigrants who had come to American “to enjoy the blessings of civil and religious liberty” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 115). Referring to American territorial acquisitions, he also observed that the people thus absorbed into the United States “under the protection of the American flag, have enjoyed civil and religious liberty, as well as equal and just laws, and have been contented, prosperous, and happy” (Inaugural Addresses 1969, 116).

Courts deal with religious freedom during Buchanan’s presidency

Buchanan was president at a time when the Supreme Court continued to follow the view announced in Barron v. Baltimore (1833) that the provisions of the Bill of Rights in the U.S. Constitution applied only to the national government and not to the states. But during Buchanan's presidency, state courts made a number of important decisions involving rights outlined in the First Amendment, relying instead on state constitutions that contained the same or similar rights.

For example, in a fairly unusual decision for the time in Ex Parte Newman (1858), the California Supreme Court overturned a law aimed at preserving the Sabbath by forbidding businesses from operating on Sunday. The California court ruled the law violated the state constitution against religious discrimination by favoring one form of religion over another and overturned the conviction of a Jewish merchant who had violated it by selling clothing on Sunday.

In Commonwealth v. Cooke (1859), a Massachusetts court upheld the right of a teacher to administer corporal punishment to a student who refused to read from the Bible at his public school, also relying on the state constitutional provisions regarding religious liberty.

In Lander v. Seaver (1859), the Vermont Supreme Court decided that a teacher could punish a student for derogatory statements he had made about the teacher while off campus. The case did not cite freedom of speech, but dealt with a student's speech that occurred outside the school setting.

At the national level, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Richardson v. Goddard (1859) that presidential proclamations of thanksgiving did not exempt individuals from fulfilling contractual obligations on such days.

Tension erupts between Utah Mormons and federal government

At a time when many individuals equated polygamy with slavery, there was increasing tension between the national government and Mormon leaders in Utah. After Buchanan removed Brigham Young, who had been appointed by President Pierce, as governor of the territory, some of his followers in 1857 attacked and killed members of an unarmed wagon train passing through the Utah Territory.

In a proclamation issued on April 6, 1858, Buchanan said that this incident and resistance to federal authority was treasonous, ordered public officials to uphold the U.S. Constitution and offered pardons to those who “shall submit to the laws.”

Buchanan made a point of indicating that he was not waging “a crusade against your religion.” He observed that “The Constitution and laws of this country can take no notice of your creed, whether it be true or false. That is a question between your God and yourselves, in which I disclaim all right to interfere. If you obey the laws, keep the peace, and respect the just rights of others, you will be perfectly secure, and may live on in your present faith or change it for another at your pleasure. Every intelligent man among you knows very well that this Government has never, directly or indirectly, sought to molest you in your worship, to control you in your ecclesiastical affairs, or even to influence you in your religious opinion.”

The offer of amnesty worked and a war against the Mormons was averted. Buchanan’s proclamation arguably set the groundwork for the Supreme Court’s later decision in Reynolds v. United States (1879), where it distinguished between freedom of religious belief and the government’s power to regulate some religiously motivated actions such as polygamy, which the Mormon Church eventually repudiated.

Raid on Harper's Ferry was an effort to start slave revolt in South

During Buchanan’s presidency, Kansas became the battleground between those who wanted the territory to be admitted as a state that guaranteed the right to own slaves and those who wanted it to enter as a free one. John Brown and his sons were among those who resorted to violence during this conflict.

On Oct. 16, 1859, Brown and his men led a raid on a U.S. arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, to seize the arsenal and its weapons and start a slave revolt in the South. Buchanan ordered the Marines to assist in retaking the arsenal, which they did. Brown's eventual hanging for the raid elevated his status among abolitionists as a martyr.

In preparing for this event, Brown had drawn up a provisional constitution that reflected his own morality. Robert Tsai, a scholar who has studied Brown's constitution, observes that it “eschews a general commitment to freedom of speech, much less an absolutist one. Instead ‘[p]rofane searing, filthy conversation, indecent behavior, or indecent exposure of the person, or ... quarreling’ are all prohibited” (Tsai 2010, 161). The proposed constitution did both prohibit an establishment of religion and guarantee its exercise (Tsai 2010, 159), but Article XLII of Brown’s proposed constitution required that “the first day of the week [shall be] regarded as a day of rest and appropriated to moral and religious instruction and improvement” (Tsai 2010, 198).

Buchanan blamed abolitionist rhetoric for divisions over slavery

Ultimately, neither the Mormon crisis nor a slave revolt split the Union, leading to the Civil War. That was accomplished as states, beginning with South Carolina, began seceding from the Union and created their own confederate government, which was headed by Jefferson Davis.

In his Fourth Annual Message to Congress, Buchanan had attempted to avoid this breach, but he did so while blaming the pending split on the rhetoric of abolitionism and the fears that it had raised among Southern whites of slave revolts. He further observed that “The time of Congress has been occupied in violent speeches on this never-ending subject, and appeals, in pamphlet and other forms, indorsed (sic) by distinguished names have been sent forth from this central point and spread broadcast over the Union.”

Buchanan did not believe that Lincoln’s election provided sufficient cause for secession, but his expansive view of states’ rights and his restrictive interpretation of presidential powers suggested that he was powerless to act. He did note that Congress had proposed the First Amendment and other provisions of the bill of rights, “which secures the people against any abuse of power by the Federal Government” and that state resistance to the Alien and Sedition Acts had resulted in their repeal.

Although he did not think he had sufficient executive power to avert the dissolution of the Union, he suggested that Congress should propose another constitutional amendment recognizing the explicit constitutional recognition of the institution of slavery, the right to carry slaves into the territories, and the obligation of states to return fugitive slaves.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Nov. 14, 2023.