On January 27 2017, President Donald J. Trump signed an executive order designed to protect the nation from terrorism by suspending immigrant and nonimmigrant entry of foreign aliens from seven predominately Muslin nations for 90 days.It further reduced the total number of refugees to be admitted in 2017 from 110,000 to 50,000 and indefinitely banned Syrian refugees.

Trump released revised executive order regarding entry of foreign aliens

After a U.S. District Judge in the Western District of Washington issued a nationwide restraining order, which the Ninth Circuit Court declined to stay, President Trump issued a new order rather than appealing to the Supreme Court. The new order restated the 90-day suspension, this time to individuals from six countries, each of which were thought to be particular terrorist threats. The new order did not, however, bar entry of lawful permanent residents or dual citizens and permitted waivers in individual cases.

Court of Appeals ruled order violated First Amendment

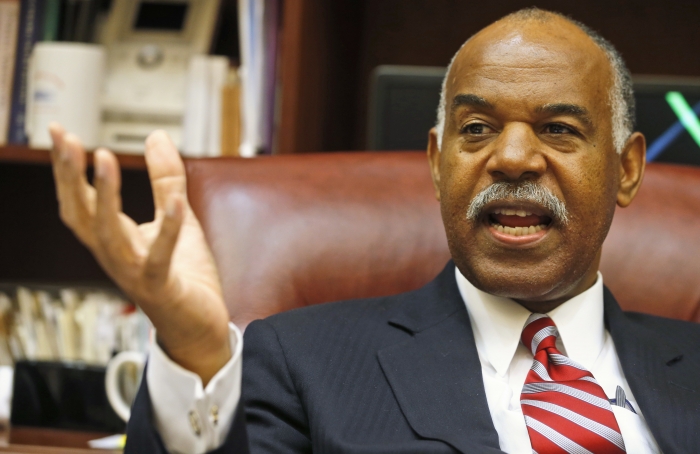

The new order was challenged and Chief Judge Roger Gregory of the Fourth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in International Refugee Assistance Project v. Trump (No. 17-1351.) that it violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment. Three others concurred in the judgement, and three dissented. Gregory observed that Trump issued both executive orders against a background of numerous statements, most made during his campaign, in which he had called for a total ban on Muslins and in which he said he would give preferences to Christians.

Gregory decided that a number of groups aiding refugees as well as a number of family members of refugees, had standing. They had challenged the order as a violation of the establishment clause of the First Amendment, equal protection of the laws, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and the Administrative Procedures Act. Because Gregory found that they had standing under the establishment clause, he did not address their other claims.

Gregory found that the harm that the plaintiffs suffered consisted both of separation from family members and from feelings of “marginalization and exclusion” because of the way the order targeted members of their religion. Gregory further denied the government’s claim that “consular nonreviewability bars any review of Plaintiff’s claim.”

Decision based on Lemon Test and discrimination

Gregory based most of his decision on the first prong on the Lemon Test (first articulated in Lemon v. Kurtzman (1973)), which requires the government to show in establishment clause challenges that its laws have a clear secular legislative purpose. Although the decision in Kleindienst v. Mandel (1972) suggested that courts would typically defer to judgments by the political branches with respect to immigration matters, such judgments must both be “facially legitimate” and must not be made in bad faith.

Based on Trump’s many statements of the subject, many during the course of the presidential campaign, Gregory thought it was clear that Trump’s orders stemmed from animus against Muslims. Moreover, evidence suggested that Trump issued his first order without even consulting “the relevant national security agencies.” Gregory did not think that the claim of national security can shield the government in cases where it is practicing discrimination.

In a concurring opinion, Judge Barbara Milano Keenan would also have based injunctive relief on the basis of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

In his concurrence, Judge James A. Wynn, Jr. said that “Invidious discrimination that is shrouded in layers of legality is no less an insult to our Constitution than naked invidious discrimination.” He believed that discrimination on the basis of religion was similar to that based on race or national origin and rested on improper stereotypes. He did not think that the statute that authorized the president to set immigration regulations, which was adopted at the time that Congress was eliminating racial considerations for immigrants, allowed for such invidious discrimination.

Judge Stephanie D. Thacker concurred in the ruling but thought that it was improper to rely on statements that Trump had made prior to becoming president.

Dissenters said national security was compelling interest

Judge Paul V. Niemeyer authored a dissenting opinion in which he accused the majority of failing to apply Kleindienst v. Mandel properly, questioned the court’s use of campaign statements, and objected to radically extending establishment clause precedents. He believed that “Congress has accorded the President broad discretion over the admission of aliens” that courts should honor. He further noted that Trump based the order at issue on the facially neutral desire to protect the nation from foreign terrorism.

Moreover, Niemeyer argued that “None of the facts or conditions recited as reasons for the issuance of the Executive Order have been challenged as untrue or illegitimate.” He further believed that his colleagues had engaged in improper “judicial psychoanalysis” of the president’s motives. He observed that “The Supreme Court has never applied the Establishment Clause to matters of national security and foreign affairs.”

Judge Dennis W. Shedd based his dissent on the government’s compelling interest in national security, and on the need for judicial deference and restraint in this area.

Judge G. Steven Agee in turn based his dissent on what he considered to be the plaintiffs’ lack of standing.

Demonstrators display placards during a rally against President Trump’s travel ban on Sunday, Jan. 29, 2017, in Boston. Among other things, the order banned legal U.S. residents and visa-holders from seven Muslim-majority nations from entering the U.S. for 90 days. Challengers alleged the ban was unconstitutional for discriminating against Muslims. After several court cases and three iterations of the ban, the Supreme Court ruled that the ban did not violate the establishment clause of the First Amendment. (AP Photo/Steven Senne, used with permission from the Associated Press.)

Supreme Court upheld parts of order

On the last day of its 2016-2017 session, in Trump v. International Refugee Assistance Project, 582 U.S. ____ (2017), the U.S. Supreme Court issued a per curiam opinion in which it upheld those parts of the injunctions that specifically applied to foreign nationals with a bona fide relationship with a person or entity in the United States, while removing it with respect to other individuals with no such connections. The Court further directed the consolidated cases to be heard during its first October 2017 session. Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, and Neil Gorsuch would have stayed the injunctions entirely, indicating that they thought the challenges to the injunctions had a good chance of success.

On October 10, 2017, the Court ruled that the appeal was moot, as the order had already expired. Following more appeals against a third iteration of the ban, the Court ruled 5-4 in June 2018 that the ban did not violate the establishment clause.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2017.