One of the most publicized lower court First Amendment decisions in recent memory, Hosty v. Carter, 412 F.3d 731 (7th Cir. 2005), stands for the principle that the framework identified by the Supreme Court in a high school press censorship case also applies at the college and university level. The Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals decided that censorship of subsidized student newspapers at colleges as well as elementary and secondary schools does not violate students’ First Amendment rights.

College reporters said censorship of college newspaper violated First Amendment

The case arose after Governors State University officials, including Dean of Students Affairs Patricia Carter, had objected to articles in the student newspaper The Innovator that were critical of the university. Carter had asked the printer to stop printing any more issues of the newspaper until she had the opportunity to review it.

Three student reporters, including Margaret Hosty, sued in federal court, contending that censorship of The Innovator violated their First Amendment rights. A federal district court granted most of the university defendants summary judgment but denied Dean Carter qualified immunity, a defense in civil rights actions that protects defendants unless they violate clearly established principles of constitutional law. A three-judge panel of the Seventh Circuit affirmed and also ruled in favor of the students. Carter appealed to the full panel of the Seventh Circuit, which reversed by a vote of 7-4 and granted Carter qualified immunity.

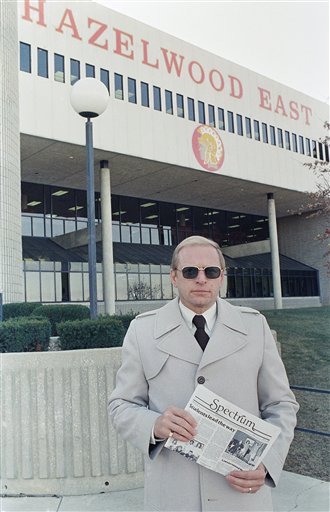

Court had previously ruled that that high school papers could be censored

Previously, in Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier (1988), the Supreme Court had ruled that high school officials could censor a school-sponsored student newspaper if they had a legitimate educational purpose for their actions. In footnote seven, the Supreme Court reserved the question as to whether Hazelwood would apply at the college level: “We need not now decide whether the same degree of deference is appropriate with respect to school-sponsored expressive activities at the college and university level.”

After the Hazelwood ruling, some lower federal courts assumed that the decision had little, if any, application at the university level. In Hosty, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals disagreed.

Circuit Court said subsidized university newspapers could be censored

Judge Frank Easterbrook, who wrote the majority opinion, determined that Hazelwood’s framework “applies to subsidized student newspapers at colleges as well as elementary and secondary schools.” This framework applies the public forum doctrine, asking whether the student newspaper operates as a public or nonpublic forum. The decision can be crucial and outcome determinative because there is greater protection for First Amendment rights in a public forum or even a limited public forum as opposed to a nonpublic forum.

Easterbrook reasoned that The Innovator may be a designated public forum or a nonpublic forum but that, in either event, Dean Carter was entitled to qualified immunity because the Supreme Court had not clearly established whether Hazelwood applied at the college level. “Public officials need not predict, at their financial peril, how constitutional uncertainties will be resolved,” he wrote.

In dissent, Judge Terence T. Evans wrote that the restrictions placed by the majority “have no place in the world of college and graduate school” and that Hazelwood “does not apply beyond high school contact.”

Student press advocates feared decision would cause more student speech censorship

Student press advocates, such as the Student Press Law Center, decried the Seventh Circuit’s failure to appreciate the legal significance of differences between students and journalists in high school as opposed to students at the college and university level. They feared that the decision would give university officials a green light to censor much school-sponsored student speech at the university level.

The students appealed the Seventh Circuit decision to the Supreme Court, but the high court declined to hear the case, thus leaving the court of appeals’ decision in place.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.