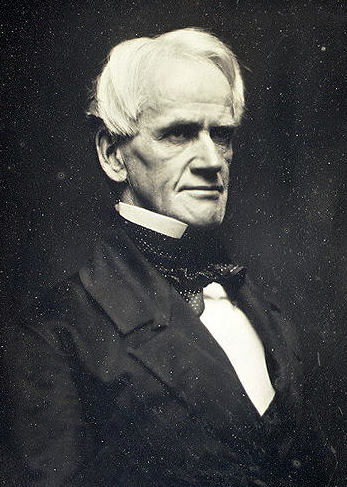

Known as the “father of American education,” Horace Mann (1796–1859), a major force behind establishing unified school systems, worked to establish a varied curriculum that excluded sectarian instruction. His vision of public education was a precursor to the Supreme Court’s eventual interpretation of the establishment clause and church-state separation principles in public schools.

Mann attended Brown University and the Litchfield Law School in Connecticut. After graduation, he built a successful legal career and was subsequently elected to the state house in 1827 and the state senate in 1833. In 1837 Mann played a key role in establishing the Massachusetts State Board of Education, and he went on to become the board’s first secretary of education.

Mann promoted universal education

As secretary, Mann advocated for “common schools,” institutions that would be available to everyone, regardless of their ability to pay tuition. Mann believed that universal education would allow the United States to avoid the rigid class systems of Europe. In his twelfth (and last) annual report for the Massachusetts school board, Mann wrote that education “is the great equalizer of the conditions of men—the balance-wheel of the social machinery.” He also argued that universal education would allow the United States to maintain a democracy; all Americans, he thought, “must, if citizens of a Republic, understand something of the true nature and functions of the government under which they live.”

Mann opposed sectarian instruction

In establishing public common schools, Mann opposed sectarian instruction and in its stead advocated instruction in universal Christian principles and values that would allow students to make their own moral judgments. Mann’s non-sectarian approach to public education was criticized at the time (and is still viewed by some today) as hostile to religion and detrimental to both individual and social morals. Some leaders of the Roman Catholic Church, for example, argued that the common schools, while professing to be nonsectarian, in fact embodied general Protestant principles, contrary to the First Amendment.

First Amendment Court holdings later upheld Mann’s nonsectarian vision

By the 1960s, in cases like Engel v. Vitale (1962) and Abington School District v. Schempp (1963), in which the Court invalidated school-sponsored prayer and Bible readings in public schools on establishment clause grounds, the Supreme Court had begun to use the establishment clause of the First Amendment to strike prayer and devotional Bible reading (usually from the King James Bible that many Protestants preferred) from the public schools.

In defense of nonsectarian schools in his last school board report, Mann argued that the common school “earnestly inculcates all Christian morals,” and “in receiving the Bible, it allows it to do what it is allowed to do in no other system,—to speak for itself. But here it stops…because [the common school] disclaims to act as an umpire between hostile religious opinions.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. David Carleton is the chair of the Department of Global Studies and Human Geography at Middle Tennessee State University.