In Gibson v. Florida Legislative Investigation Committee, 372 U.S. 539 (1963), the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment rights of free speech and association protected organizations from having to divulge their membership to a legislative investigative committee when there was an insufficient record to demonstrate an association with communist activity.

Gibson ordered to divulge NAACP membership records

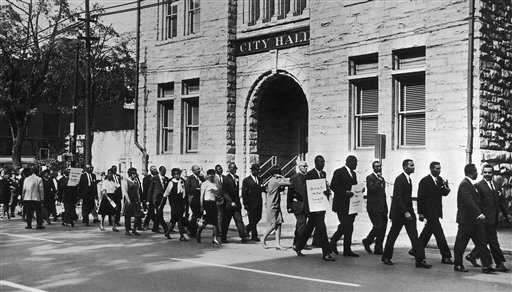

Theodore R. Gibson was the president of the Miami branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) when the Florida state legislature ordered him to appear before one of its committees investigating the alleged communist infiltration of organizations active in the field of race relations.

When the committee scheduled Gibson to appear, it also ordered him to bring the organization’s membership records. Gibson argued that having to bring the records and answer questions concerning who belonged to the organization violated the associational right of NAACP members and prospective members, so he refused the request. A Florida state court adjudged him in contempt of the legislature, and the Florida Supreme Court affirmed.

Legislature did not suggest NAACP was a subversive organization

The legislature did not suggest that the Miami branch was a subversive organization or had been communist dominated or influenced. Rather, the purpose of Gibson’s testimony was to determine whether 14 persons who had been identified as communists or members of communist-front or communist-affiliated organizations were members of the Miami NAACP. The primary evidence the committee relied upon to demonstrate a relationship between the NAACP and communist activities was tenuous hearsay testimony by two witnesses.

State must show compelling interest to intrude on First Amendment rights

Writing for the 5-4 U.S. Supreme Court, Justice Arthur J. Goldberg pointed out that Gibson involved a conflict between individual rights of free speech and association and the governmental interest in conducting legislative investigations. He distinguished this case from Barenblatt v. United States (1959) by pointing out that Barenblatt had focused on membership in the Communist Party, whereas in Gibson there was no evidence to believe that the NAACP was subversive or communist dominated or influenced.

Goldberg then declared that when the claim is made that a legislative investigation intrudes upon First and Fourteenth Amendment associational rights of individuals, the state must show convincingly a substantial relation between the information sought and the subject of investigation, which had to involve a compelling state interest. In this case, the state had failed to demonstrate a substantial relationship between the NAACP and communist infiltration of organizations trying to improve race relations.

Justice Hugo L. Black concurred but believed that even unpopular groups, such as communists, had the right to associate. Justices John Marshall Harlan II and Byron R. White dissented separately, both expressing concern that the decision would weaken the government’s ability to investigate communist activities.

This article was originally published in 2009. Tom McInnis earned a Ph.D. from the University of Missouri in Political Science in 1989. He taught and researched at the University of Central Arkansas for 30 years before retirement. He published two books and multiple articles in the area of civil liberties and the American legal system.