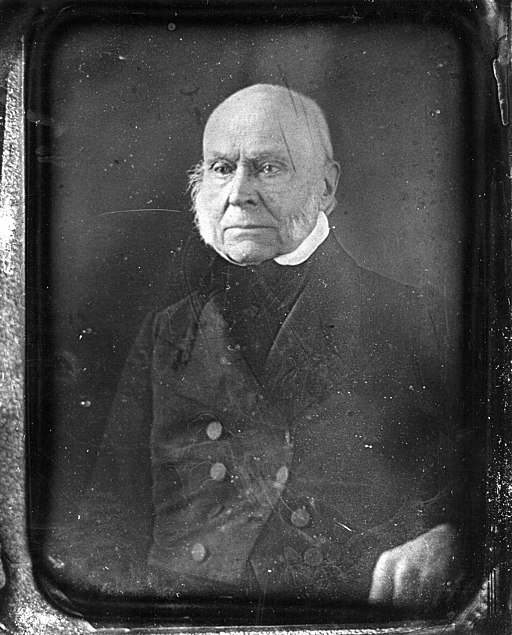

In the 1830s and 1840s in the U.S. House of Representatives, former president John Quincy Adams led an eight-year struggle against a southern-sponsored gag rule denying the presentation or discussion of antislavery petitions.

Elected to Congress in 1831, Adams, though never an abolitionist, opposed the extension of slavery to the territories and presented a petition from 22 slaves in 1837 for emancipation. Irate southerners threatened to have him barred from Congress.

U.S. House adopted gag rule to ignore anti-slavery petitions

Consistent with the provision in the First Amendment providing for the right of the people “to petition the Government for a redress of grievances,” the American Anti-Slavery Society, founded in 1833, submitted petitions to Congress in favor of abolishing slavery in the District of Columbia and the new territories and protesting the admission of Texas, a slave territory, into the Union.

In 1836 a resolution introduced by Henry Laurens Pinckney of South Carolina provided that such petitions be laid on the table and ignored. Northern Democrats, who regarded the petitions as inflammatory and threatening to the Union, supported Pinckney’s position and also argued that the petitions took too much of the lawmakers’ time.

Adams had initially avoided the antislavery battles, but then decided to move to strike the offending gag rule at the beginning of each session, when the House adopted its rules of procedure.

In 1844, after northern Democratic support for the gag rule had diminished, Adams’s motion to repeal the standing 21st rule of the House carried by a vote of 108-80.

Senate never passed gag rule, despite efforts by Southern lawmakers

The Senate never passed a similar rule limiting debate on anti-slavery petitions despite efforts by Southern lawmakers, most notably John C. Calhoun.

This article was originally published in 2009. Martin Gruberg was President of the Fox Valley Civil Liberties Union in Wisconsin.