In Federal Communications Commission v. Fox, 556 U.S. 502 (2009), the U.S. Supreme Court narrowly determined 5-4 that the FCC did not act arbitrarily and capriciously under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) by changing its policy with regard to fleeting expletives. The Court declined to address the underlying First Amendment free speech issues in its decision.

In FCC v. Pacifica Foundation (1978), the Court held that the FCC could fine a radio station for playing George Carlin’s “Filthy Words” monologue during daytime hours. The Court reasoned that the FCC had the power under 18 U.S.C. §1464 which prohibits the broadcasting of indecent and obscene expression.

FCC did not punish ‘fleeting expletives’ for many years

For many years, the FCC declined to sanction radio and television stations for broadcasting so-called fleeting expletives. However, the commission changed course many years later and attempted to impose liability on Fox after several celebrities uttered profanity on music award shows. For example, musician Sonny Bono stated on a Golden Globes broadcast: “This is really, really, f—king brilliant.”

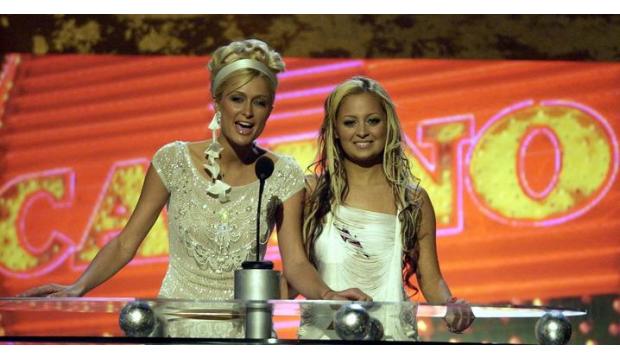

In the present case, the singer Cher exclaimed at the 2002 Billboard Music Awards about critics: “F— em.” At the 2003 Billboard Music Awards, reality TV star Nicole Richie said: “It’s not so f—ing simple.” The FCC declared that these utterances on live broadcast television constituted impermissible indecency.

Fox battled FCC after new sanctions for ‘fleeting expletives’

Fox battled the FCC over the order and new policy on “fleeting expletives.” The 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals determined that the FCC violated the APA by suddenly changing course with regard to fleeting expletives. The 2nd Circuit did not address the First Amendment arguments, including whether Pacifica was still good law.

Court said FCC’s new policy was not ‘capricious’

On further appeal, the U.S. Supreme Court determined that the FCC did not violate the APA. Writing for the majority, Justice Antonin Scalia reasoned that the FCC’s actions were neither arbitrary nor capricious. He wrote that “the agency’s reasons for expanding the scope of its enforcement activity were entirely rational” and noted the F-word’s “power to insult and offend derives from its sexual meaning.”

Court did not address First Amendment issue

Scalia and the Court did not address the underlying First Amendment arguments, because the 2nd Circuit had not addressed them. Thus, the Court remanded the case back to the 2nd Circuit to address these underlying free speech arguments.

Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurring opinion, agreeing with the majority’s rationale with regard to the APA. However, he noted the “questionable viability” of both Red Lion Broadcasting v. FCC (1969) and Pacifica. Justice Anthony Kennedy concurred, offering additional reasons why the FCC did not violate the APA.

Dissenting justices thought policy was questionable under First Amendment

Justices John Paul Stevens, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, and Stephen Breyer all wrote dissenting opinions. Stevens, who had authored the Pacifica opinion years earlier, said the FCC “has ventured far beyond Pacifica’s reading of §1464.”

Ginsburg wrote that “there is no way to hide the long shadow the First Amendment casts over what the Commission had done.” She, like Justice Thomas, questioned the viability of Pacifica.

For his part, Breyer wrote that the FCC failed to adequately explain its policy change with regard to fleeting expletives. He considered the FCC’s change to be “arbitrary, capricious, [and] an abuse of discretion.”

Policy was eventually ruled to be unconstitutionally vague

Eventually, the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court again, and in FCC v. Fox (2012), the Court invalidated the FCC’s policy as unconstitutionally vague.

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.