In Ex parte Jackson, 96 U.S. 727 (1878), the Supreme Court ruled that Congress did not violate the free speech clause of the First Amendment by closing the postal system to literature concerning lotteries, although it lacked the constitutional authority to prevent such materials from circulating by other means.

Federal government started mail ban on lottery literature in 1876

Government control of lotteries, moderate during the first half of the 19th century, had stiffened during the second half, and most states banned lotteries outright. The federal government started the mail ban in 1876.

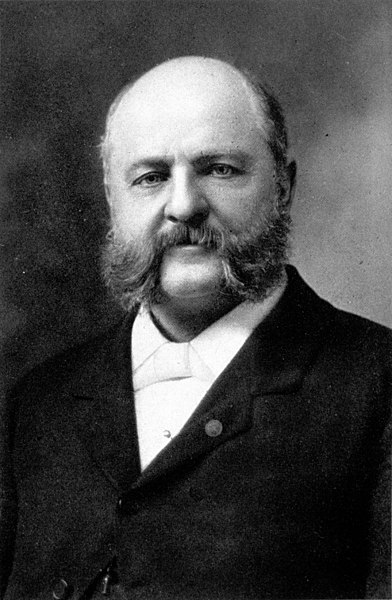

A zealous “special agent of the post office,” Anthony Comstock, arrested dozens of lottery dealers, including A. Orlando Jackson, and charged them with violating the new federal law. Jackson protested his arrest as a violation of his freedom of expression. He insisted that Congress had no power “to prohibit the transmission of intelligence,” through the mails or otherwise. He also warned of a slippery-slope threat to commerce.

Court said mail ban did not violate First Amendment freedoms

Neither argument impressed Justice Stephen F. Field, who wrote the decision for the court. Field admitted that free circulation was vital to a free press, but he denied that the postal ban prevented free circulation. Items barred from the mails remained free to circulate in other ways, he maintained. Congress did not abridge press freedom, he asserted, but merely refused to abet the distribution of matter that it deemed immoral.

Anti-lottery laws strengthened in the wake of Jackson. All states but Louisiana prohibited lotteries entirely.

Congress made it a crime to transport lottery tickets across state lines

In 1895, Congress, in a path-breaking attempt to use its interstate commerce power as a way to exert a federal police power over public morals (a power generally reserved to the states), made it a federal crime to transport lottery tickets or advertisements across state lines, through the mails or otherwise.

The Supreme Court upheld this statute in Champion v. Ames (1903), thus sanctioning the exercise of a federal police power.

This article was originally published in 2009. John Wertheimer is the William R. Kenan, Jr. Professor of History at Davidson College, in North Carolina.