In Employment Division, Department of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith, 494 U.S. 872 (1990), the Supreme Court changed religious free exercise law dramatically by ruling that generally applicable laws not targeting specific religious practices do not violate the free exercise clause of the First Amendment. The Court abandoned the compelling interest test that it had used in free exercise cases since 1963 in Sherbert v. Verner.

Smith and Black denied unemployment benefits for smoking peyote in a religious service

The case began when Alfred Smith and Galen Black were fired from their jobs as private drug rehabilitation counselors for ingesting peyote as part of a sacrament of the Native American Church. When Smith and Black applied for unemployment benefits, the Employment Division denied their request because they had violated a state criminal statute. Smith then brought suit against the Employment Division and won his case in the lower courts. The Supreme Court reversed the decision, holding that Smith’s and Black’s free exercise rights were not violated.

Court said denial of benefits did not violate the First Amendment

In writing the opinion of the Court, Justice Antonin Scalia held that the denial of unemployment benefits to a member of the Native American Church for using the illegal drug peyote in the practice of his religion was not a violation of the free exercise clause of the First Amendment.

Court said Oregon had legitimate interest in combatting drugs

Scalia wrote that there have been two types of free exercise cases, hybrid and pure. In hybrid cases, the Supreme Court used the strict scrutiny standard, in which the state must show that it has a compelling governmental interest and uses the least restrictive means of fulfilling that interest. Hybrid cases involve a constitutional right coupled with another fundamental right; for example, parental rights plus a First Amendment right, as in Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972).

In purely religious cases, the Court used the valid secular policy test, in which the state has a lighter burden in demonstrating that the law has a legitimate governmental interest and is neutrally applied. The Court held that Smith was a purely religious case, because it only involved violating a criminal statute. Using the valid secular policy test, the Court held that combating a national drug problem was a legitimate governmental interest and that the law was neutrally applied to all citizens of Oregon. Scalia concluded the Court’s opinion by musing that precluding Smith from practicing his religion was the inevitable ramification of living in a democratic regime.

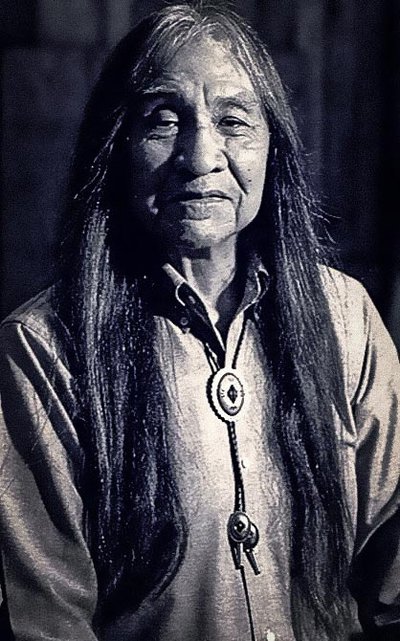

Emerson Jackson, a Native American Church holyman, performs a cedar ceremony outside the Supreme Court in 1989 after the Court heard arguments which may decide whether the American Church participants have a constitutional right to use peyote, a small cactus with hallucinogenic properties, in their religious practices. The Court decided that they do not. (AP Photo/Rick Bowmer, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Other justices said strict scrutiny standard should be used

In concurrence, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor argued that the strict scrutiny standard should be used in all free exercise clause cases. O’Connor claimed that the state’s interest in safety, health, and order would pass the strict scrutiny standard.

In dissent, Justice Harry A. Blackmun, like O’Connor, asserted that the Court should continue to apply the prevailing standard of strict scrutiny. He notes, however, that the state would not pass this standard, because peyote has nothing to do with the national drug problem in the United States.

Later laws looked at strict scrutiny tests in First Amendment cases

The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993, which mandated the Court’s use of strict scrutiny in free exercise clause cases, would later reverse the Court’s decision in Smith and restore the compelling interest test from Sherbert v. Verner (1963).

Four years later, however, in City of Boerne v. Flores (1997), the Court ruled that RFRA was unconstitutional because it represented an attempt by Congress to overrule a Supreme Court decision in violation of the concept of separation of powers.

In Cutter v. Wilkinson (2005), however, the Court upheld provisions of the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act of 2000 (RLUIPA), which applied this standard to religious land uses and to persons incarcerated in prisons and in mental institutions.

This article was originally published in 2009. John Hermann has been a professor at Trinity University for the 25 years where he teaches on Civil Rights and Liberties. He is an expert in minority rights and the Supreme Court of the United States.