In Doe v. Gonzales, 546 U.S. 1301 (2005), Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, acting in her capacity overseeing the 2nd U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, denied an application by a member of the American Library Association (designated John Doe) and others to overturn an order by the 2nd Circuit that had stayed a U.S. district court injunction against a provision of the USA Patriot Act prohibiting librarians from disclosing that the FBI had requested information about a patron in a national security letter.

Library prohibited from disclosing FBI had requested information on a patron

In this instance, the bureau had demanded details about a visitor’s electronic communications. The 2nd Circuit had issued the order while granting expedited review of the district court’s ruling that the provision was unconstitutional.

Doe had challenged the provision as an unlawful prior restraint that restricted his ability to provide firsthand information about the debate surrounding this provision of the law.

Court upheld secrecy of FBI letter, denied First Amendment challenges

Ginsburg noted that the government had advanced a “mosaic theory,” by which while agreeing that the identity of Doe’s patron might prove innocuous by itself, it “could still be significant to a terrorist organization when combined with other information available to it.”

Although acknowledging the cogency of some of the applicants’ arguments, Ginsburg observed that she could not justify interfering with an interim order simply because she “disagrees about the harm a party may suffer.”

She further stated, “Respect for the assessment of the Court of Appeals is especially warranted when that court is proceeding to adjudication on the merits with due expedition.” She argued that she owed special deference to the appeals court because it was reviewing a decision by a district court holding a congressional law to be unconstitutional.

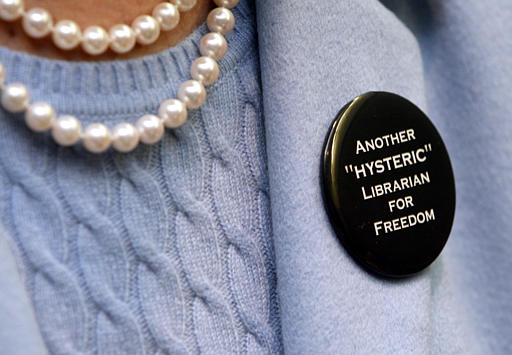

In somewhat minimizing the issue of prior restraint, Ginsburg further observed that the American Library Association was free to note that one of its members had been served with a national security letter.

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.