The Supreme Court ruled in Dawson v. Delaware, 503 U.S. 159 (1992), that the First Amendment imposes limitations on the introduction of a criminal defendant’s group associations during sentencing.

Dawson contended that introducing evidence of gang association in a trial violated his First Amendment rights

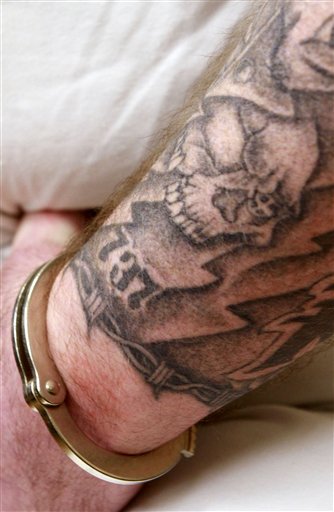

David Dawson, a prison escapee, was convicted of crimes including murdering a woman while committing a burglary. During the penalty phase of the trial, prosecutors introduced evidence that Dawson was a member of — and had tattooed on his right hand the name of — the Aryan Brotherhood, a prison gang with racist beliefs.

Prosecutors submitted a stipulation to the court that read: “The Aryan Brotherhood refers to a white racist prison gang that began in the 1960’s in California in response to other gangs of racial minorities. Separate gangs calling themselves the Aryan Brotherhood now exist in many state prisons including Delaware.”

Although Dawson agreed to the stipulation to prevent the state from introducing further evidence about the gang, he contended that the introduction of this evidence violated his First Amendment free association rights. The trial court imposed the death penalty, which the Delaware Supreme Court affirmed.

Court said defendant’s association was not relevant to his crime

On appeal the U.S. Supreme Court agreed 8-1 that introducing Dawson’s association with the Aryan Brotherhood infringed on his First Amendment rights. Writing for the Court, Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist declared that “the receipt into evidence of the stipulation regarding his membership into the Aryan Brotherhood was constitutional error.”

Rehnquist determined that the First Amendment “does not erect a per se barrier to the admission” of evidence of beliefs and association. In this case, however, Rehnquist explained that Dawson’s alleged association was not relevant to the crime he committed.

Both Dawson and his victim were white; “elements of racial hatred were therefore not involved in the killing.”

To Rehnquist these circumstances distinguished Dawson from Barclay v. Florida (1983), in which the Court ruled that a judge could consider defendant Elwood Barclay’s membership in the Black Liberation Army in sentencing him for the death of a white woman.

Rehnquist noted that “on the present record one is left with the feeling that the Aryan Brotherhood evidence was employed simply because the jury would find these beliefs morally reprehensible.”

Justice Clarence Thomas dissented, finding evidence of Dawson’s gang membership relevant to his character. He added that “the Due Process Clause, not the First Amendment, traditionally has regulated questions about the improper admission of evidence.”

David L. Hudson, Jr. is a law professor at Belmont who publishes widely on First Amendment topics. He is the author of a 12-lecture audio course on the First Amendment entitled Freedom of Speech: Understanding the First Amendment (Now You Know Media, 2018). He also is the author of many First Amendment books, including The First Amendment: Freedom of Speech (Thomson Reuters, 2012) and Freedom of Speech: Documents Decoded (ABC-CLIO, 2017). This article was originally published in 2009.