In Clark v. Community for Creative Non-Violence, 468 U.S. 288 (1984), the Supreme Court ruled 7-2 that a National Park Service regulation prohibiting camping in national parks in places other than designated campgrounds did not violate the First Amendment even when camping was a form of symbolic speech.

Demonstrators planned to sleep in tents across from White House

The case began when the Community for Creative Non-Violence (CCNV) sought an injunction against the park service’s regulation prohibiting camping so it could hold a demonstration in Lafayette Park, across from the White House, and on the National Mall to highlight the plight of the homeless. The demonstrators planned to sleep in tents to demonstrate how the homeless live.

The district court found in favor of the park service, but the federal appeals court overturned the ruling, finding that the regulation infringed the demonstrator’s free expression. The Supreme Court reversed.

Court finds First Amendment symbolic expression subject to time, place, manner restrictions

Agreeing that sleeping in tents to show support for the plight of the homeless was a form of symbolic speech, Justice Byron R. White, writing for the Court, also found that it fell within the definition of camping forbidden by park service regulations.

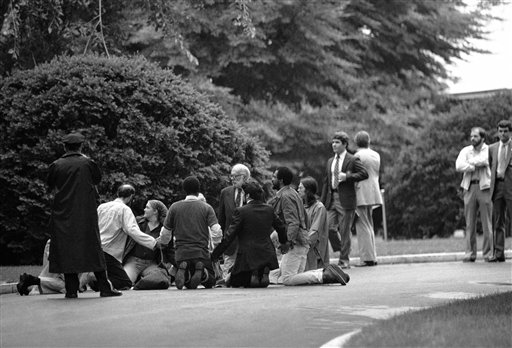

Efforts to camp overnight at the National Mall as part of protests was not new when the Community for Creative Non-Violence sought an injunction against rules prohibiting it. In this April 21, 1971 photo, Vietnam War protesters are shown camping out at the National Mall. At the time, Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren E. Burger issued an order barring the group from camping out on the Mall, but they remained for a period with no effort made to remove them. (AP Photo/Henry Burroughs, used with permission from The Associated Press.)

He noted that symbolic expression is subject to reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions. For guidance in determining whether these regulations were acceptable, the Court turned to United States v. O’Brien (1968).

In applying the O’Brien test, the regulation first had to be within the power of the government. The Court found that the government had an adequate foundation of power to enact the regulation. In this particular case, the regulation against camping had not been made for the purpose of limiting the expression of any form of ideas. Rather, the regulation had been narrowly crafted to further the substantial governmental interest of protecting national parks so that they can be enjoyed by millions of people.

The need to protect the national parks extended to Lafayette Park and the National Mall, which would be substantially changed if camping were allowed there. White also found that the regulation left ample opportunities for demonstrators to express their views, specifically pointing out that the park service had granted a permit in response to a CCNV request to set up 20 tents in Lafayette Park and 40 tents on the National Mall.

Justice Thurgood Marshall, joined by William J. Brennan Jr., dissented, believing the demonstrators’ sleeping to be a form of protected symbolic speech.

This article was originally published in 2009. Tom McInnis earned a Ph.D. from the University of Missouri in Political Science in 1989. He taught and researched at the University of Central Arkansas for 30 years before retirement. He published two books and multiple articles in the area of civil liberties and the American legal system.