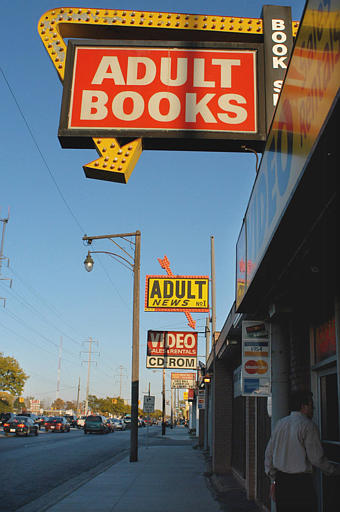

In City of Littleton v. Z.J. Gifts D-4, L.L.C., 541 U.S. 774 (2004), the Supreme Court upheld a Littleton, Colorado, adult business licensing ordinance against an adult bookstore. The store had launched a facial challenge to the law rather than applying for a license that would have permitted such a store in a location not zoned for such adult businesses.

Case dealt with ‘prompt judicial review’ v. ‘prompt judicial determination’

The decision lowered a city’s burden with respect to providing “prompt judicial review,” as articulated in Freedman v. Maryland (1965), in adult business licensing decisions.

Littleton had claimed that it was sufficient to guarantee “prompt access” to judicial review of a license denial rather than a “ ‘prompt judicial determination’ of the applicant’s legal claim.” Justice Stephen G. Breyer, writing for the Court, rejected this notion, but accepted the city’s claim that its law satisfied “any ‘prompt judicial determination’ requirement.”

Court said law satisfied ‘prompt judicial determination’ requirement

In rejecting the city’s first claim, Breyer refused to accept the distinction that the city had tried to make between the decisions in Freedman v. Maryland (1965) and FW/PBS, Inc. v. City of Dallas (1990), respectively, striking down prior restraint of movies and a scheme for licensing sexually oriented businesses.

Breyer saw no evidence, however, that the courts would not provide prompt decisions. He observed first that “ordinary court procedural rules and practices, in Colorado as elsewhere, provide reviewing courts with judicial tools sufficient to avoid delay-related First Amendment harm.” Breyer saw no reason “to doubt the willingness of Colorado’s judges to exercise these powers wisely so as to avoid serious threats of delay-induced First Amendment harm.”

Court upheld ordinance

He also observed that the licensing scheme at issue involved “reasonably objective, nondiscretionary criteria unrelated to the content of the expressive materials that an adult business may sell or display” and that the city was not required specifically “to place judicial review safeguards all in the city ordinance that sets forth a licensing scheme.”

In a concurring opinion, Justice Antonin Scalia suggested that “the notion that media corporations have constitutional entitlement to accelerated judicial review of the denial of zoning variances is absurd.”

He further linked the business at issue to pandering, which on the authority of Ginzburg v. United States (1966) he did not believe had constitutional protection. Justice John Paul Stevens wrote a separate concurring opinion adding that the First Amendment was relevant to this licensing scheme and that the law needed to ensure more than the more “possibility of a prompt decision.”

Justice David H. Souter, joined by Anthony M. Kennedy, wrote another concurring opinion, asserting that because the law did not involve “full-blown censorship,” it “does not need a strict timetable of the kind required by Freedman v. Maryland . . .to survive a facial challenge.”

John Vile is professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. He is co-editor of the Encyclopedia of the First Amendment. This article was originally published in 2009.