In City of Ladue v. Gilleo, 512 U.S. 43 (1994), the Supreme Court ruled that city officials could not flatly prohibit homeowners from displaying political signs on their own property.

Gilleo was not allowed to display a political sign in her yard

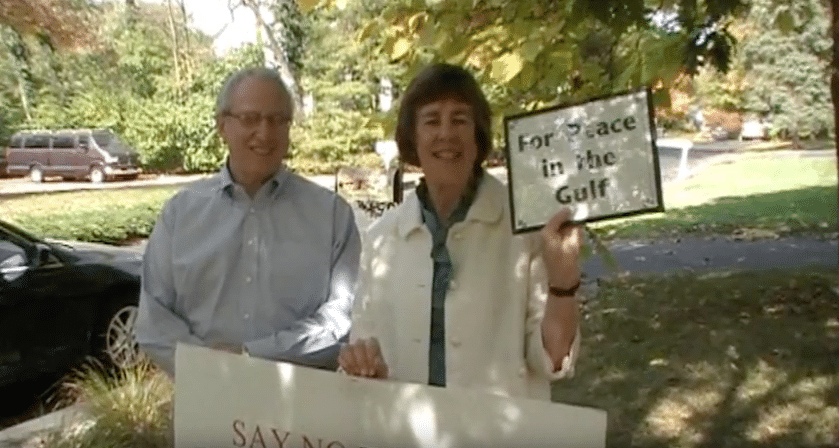

In December 1990, Margaret Gilleo hammered a 2-foot-by-3-foot sign into her lawn in Ladue, an upperclass suburb of St. Louis. The sign read “Say No to War in the Persian Gulf. Call Congress Now.”

When Gilleo learned that the sign violated a city ordinance, she approached the city council for an exemption and was denied. Gilleo then sued the city, claiming that the ordinance violated her First Amendment right of free speech. As the case moved through the legal system, Gilleo removed the sign from her lawn and placed one in a bedroom window that read “For Peace in the Gulf.” The sign in the window also violated the city ordinance.

Court said ordinance against political signs stopped important form of expression

Writing for a unanimous Court, Justice John Paul Stevens explained that Ladue’s anti-sign law was unconstitutional because it closed off a traditional form of expression.

The ordinance, he wrote, has “almost completely foreclosed a venerable means of communication that is both unique and important. It has totally foreclosed that medium to political, religious, or personal messages.” The Court’s decision upheld a ruling by the Eighth Circuit Court of Appeals, but used different analyses. Noting that the ordinance forbade most signs but allowed others, such as “For Sale” signs, the circuit court ruled the law unconstitutional because it failed to be content neutral; it favored commercial speech over noncommercial speech.

The Supreme Court bypassed the question of content neutrality, choosing instead to accept the council’s contention that it did not intend for the law to discriminate based on signs’ messages.

Court said entire avenues of expression could not be banned

The Supreme Court relied on previous decisions taking issue with banning entire avenues of expression.

These decisions included:

- Lovell v. City of Griffin (1938), dealing with the distribution of pamphlets, and

- Jamison v. State of Texas (1943), concerning handbills on public streets.

The Court found that the Ladue ordinance eliminated a “cheap and convenient form of communication.”

“Even for the affluent,” Stevens wrote, “the added costs in money or time of taking out a newspaper advertisement, handing out leaflets on the street, or standing in front of one’s house with a hand-held sign may make the difference between participating and not participating in some public debate.”

Court does not prohibit city sign regulation

Despite the ruling, Stevens noted that sign regulation is within a municipality’s police powers: “The decision reached here does not leave Ladue powerless to address the ills that may be associated with residential signs. In addition, residents’ self-interest in maintaining their own property values and preventing ‘visual clutter’ in their yards and neighborhoods diminishes the danger of an ‘unlimited’ proliferation of signs.”

This article was originally published in 2009. Dr. Neil Ralston worked as a reporter and editor for 10 years before beginning a career as a journalism teacher at the college level in 1989. His Ph.D. dissertation focused on the First Amendment attitudes and knowledge of high school students. From 2007 to 2013, he served as a vice president on the board of directors of the Society of Professional Journalists where he worked with students and advisers at college media outlets who faced censorship attempts. He now teaches at Lindenwood University in St. Charles, Missouri.