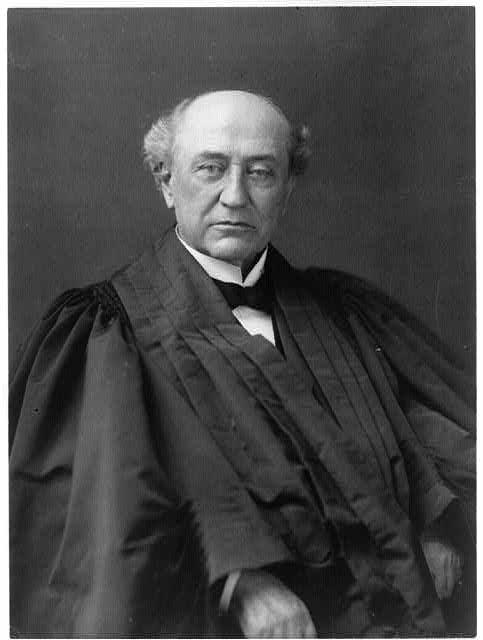

Church of the Holy Trinity v. United States, 143 U.S.457 (1892), involving the application of a federal law forbidding the importation of foreign contract laborers, is notable for Justice David J. Brewer declaring that the United States is a “Christian nation.”

Court ruled in favor of church that illegally hired clergyman

When the Church of the Holy Trinity hired a clergyman from England to serve as its pastor, it was charged with violating the law in question.

A lower court ruled against the church, but the Supreme Court reversed. Although agreeing that the action of the church technically violated the statute, Brewer used legislative intent to conclude that the church’s action was unrelated to Congress’s purpose in passing the law — stopping the flow of cheap unskilled foreign labor.

Brewer’s opinion said America was ‘a Christian nation’

Brewer added that a legislature representing a religious people would certainly not take action against religion. He provided an overview of references to God in official documents from U.S. history, beginning with the commission to Christopher Columbus and continuing through colonial charters, state constitutions, and oaths of office.

Turning to the Constitution, he offered the First Amendment and the “Sundays excepted” provision in Article 1 as evidence of the importance of religion in the United States. He also found throughout American life — from its laws to its businesses, customs, and multitudes of churches, charitable organizations, and missionary associations — further evidence that “this is a Christian nation.”

Justice Brewer did not make clear whether by “Christian nation” he meant “government” in a legal sense or whether he was observing that most Americans claimed to practice Christian morality or listed Christianity as their religion. Of interest, in L’Hote v. City of New Orleans (1900), Brewer, who wrote the Court’s opinion in favor of New Orleans, did not refer to or echo his Holy Trinity dicta at all, although the topic of this case — legalized prostitution — and one of the plaintiffs — the Methodist Church — would have made this the ideal occasion to employ his “Christian nation” standard.

Others thought America should be recognized as a ‘Christian nation’

Brewer was not the first to make this assertion. Some state courts in the nineteenth century had also referred to the United States as a Christian nation or suggested that Christianity should receive special favoritism.

In 1864 a Protestant organization asked Congress to amend the preamble to the Constitution to define the national government as a Christian one.

Brewer’s ‘Christian nation’ phrase lives on

In 1905 Brewer published a series of lectures under the title The United States: A Christian Nation, further explaining his thoughts on this topic. The book is replete with examples from history and from state courts and constitutions of official references to Christianity, but Brewer also observed that the United States cannot be called a Christian nation “in the sense that Christianity is the established religion or that the people are in any manner compelled to support it” (Brewer 1905:12).

Brewer’s “Christian nation” phrase has almost never been quoted in subsequent Court opinions.

Nonetheless, the phrase lives on in the writings and speeches of critics of the wall of separation metaphor that has shaped the Court’s thinking since incorporation of the establishment clause in Everson v. Board of Education (1947). It is also the source of assertions by the Christian Right that the Supreme Court once declared the United States to be a “Christian nation.”

For example, the evangelist Pat Robertson, in a fund-raising letter for his American Center for Law and Justice, wrote, “One hundred years ago, a landmark Supreme Court ruling reaffirmed America’s identity as a Christian nation”(Boston 1993:10).

This article was originally published in 2009. Jane G. Rainey is a professor emeritus of political science at Eastern Kentucky University. She specializes in politics and religion in the United States. She speaks to civic and church groups on First Amendment establishment clause issues and the role of churches and faith-based groups in influencing public policy.