Child pornography, a form of sexual expression often involving the depiction of children engaged in sexually explicit conduct, is not entitled to First Amendment protection.

It is similar to obscenity in that it represents a category of sexual expression lacking First Amendment protection, but it covers material that does not meet the legal definition of obscenity.

Courts have voided child pornography laws that are overbroad

The federal and state governments have passed numerous statutes outlawing child pornography and protecting children from obscenity, but they have only been somewhat successful. Courts have applied the generally speech-protective strict scrutiny standard, which requires that the government demonstrate a compelling interest and ensure that a law is narrowly tailored to achieve that interest by using the least restrictive means. Courts have routinely voided laws that are overbroad and therefore reach protected speech.

Child pornography generally encompasses two different but related issues:

- criminal prohibitions on the production, distribution, and possession of depictions of children engaging in sexual activity and

- the ability of children to view pornography (particularly via the Internet).

The overriding concern of legislators in criminalizing child pornography is its link to the actual sexual abuse of children, a justification generally sustained by courts despite First Amendment free speech objections.

Two Supreme Court precedents govern child pornography law. One concerns obscenity generally, while the other is specific to child pornography.

Miller Test is used to determine obscene materials not protected by the First Amendment

In Miller v. California (1973), the Court articulated a three-part test to determine obscenity. Under Miller, material is obscene if:

- The average person in the community would find the work’s predominant theme “prurient”;

- It depicts sexual conduct in a patently offensive way; and

- When taken as a whole it “lacks serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.”

In the second key precedent, New York v. Ferber (1982), the Court upheld prohibitions on the production and distribution of child pornography because of their direct link to the sexual abuse of minors.

Congress toughens laws against child pornography, 1977-1986

Congress first passed legislation against child pornography with the Protection of Children against Sexual Exploitation Act of 1977, which made it a crime knowingly to use a minor under 16 years of age in obscene depictions of sexually explicit conduct.

Congress subsequently toughened the statute with the Child Protection Act of 1984 by omitting the obscenity requirement, raising the minor’s age from 16 to 18, and including not-for-profit distribution.

It next revised the law with the Child Sexual Abuse and Pornography Act of 1986, which proscribed advertising for child pornography and created a civil liability for personal injuries to minors from the production of child pornography.

All of this legislation passed prior to the widespread use of the Internet. As child pornography flourished online, Congress strengthened the existing statutes.

Congress begins addressing child pornography via computers

The first statute passed to address the technological developments expanding child pornography was the Child Protection and Obscenity Enforcement Act of 1988, which criminalized transporting, distributing, or receiving child pornography via computer.

State laws were also passed to address this issue. The Supreme Court sustained one of these in Osborne v. Ohio (1990) in upholding a prohibition on the private possession and viewing of child pornography in one’s own home.

This decision cleared the way for a similarly strict ban at the national level, leading Congress to pass the Child Protection Restoration and Penalties Enhancement Act of 1990, which criminalized the knowing possession of child pornography.

In passing the Child Pornography Prevention Act of 1996 (CPPA), Congress shifted from primarily approaching child pornography through its link to the actual sexual abuse of children to raising the issue of morality, banning even “virtual” child pornography, in which no actual children are used in producing the material.

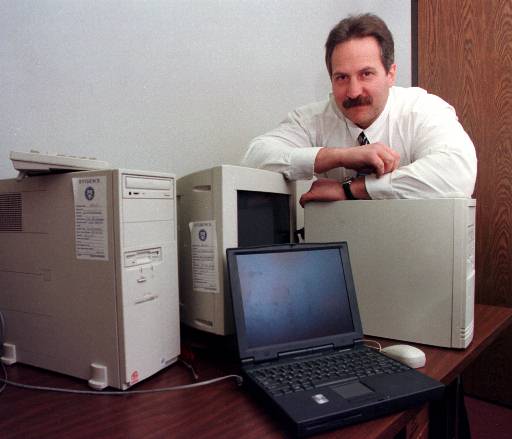

Donald Daufenbach, a senior special agent with the U.S. Customs Service, poses with some of the computers that have been seized in an ongoing child pornography case Feb. 3, 1999, in Salt Lake City. Before the explosion of child pornography on the Internet, Daufenbach worked undercover in the drug world. He says he perfected a “dirtbag” look so subtle in its nuances that people scurried across the street to avoid him. But when Daufenbach goes undercover today, he simply sits at his computer to enter another netherworld of crime. (AP Photos/Douglas C. Pizac, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court strikes down law criminalizing possession of child pornography

In Ashcroft v. Free Speech Coalition (2002), the Supreme Court stuck down key sections of the legislation as overly broad because it banned a “significant universe of speech that is neither obscene under Miller nor child pornography under Ferber.”

As examples of the kind of material that could be prohibited under the CPPA, the Court listed a picture in a psychology manual and well-known, award-winning theatrical films that portray minors having sex, such as Romeo and Juliet, American Beauty, and Traffic.

The Court explained that “in contrast to Ferber, CPPA prohibits speech that records no crime and creates no victims by its production.” Indeed, the Court pointed out that the majority in Ferber reasoned that young-looking adults could be used if necessary for scientific and artistic purposes.

One of the reasons given by legislators for passing statutes protecting children from viewing pornography is that adults use such material to lure children into engaging in sexual activity. Of course, general moral concerns are also part of the equation.

Congress’s first action in this area was its passage of the Communications Decency Act of 1996 (CDA), which attempted to incorporate the Miller obscenity test and sought to limit the exposure of children to sexually explicit material on the Internet.

Courts reject laws based on “overbreadth” standard

In Reno v. American Civil Liberties Union (1997), the Supreme Court struck down key provisions of the CDA because they failed to specifically define the terms indecent and patently offensive and were likely to “chill,” or silence, constitutionally protected speech, that is nonobscene speech targeted at adults.

Congress responded to the Court’s decision with the

In Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union (2002), the Court said that the community standards language did not in itself invalidate the law, but that it still might be unconstitutional for other reasons.

The Court remanded the case to the court of appeals, where COPA was struck down. The case returned to the Supreme Court in Ashcroft v. American Civil Liberties Union (2004), and the 6-3 majority agreed with the lower court’s ruling that COPA was not narrowly tailored and that less restrictive means, such as filtering software, existed for protecting children from otherwise constitutionally protected speech.

Since COPA, Congress has continued to legislate in this area. Federal law now prohibits misleading Internet domain names, like the infamous “whitehouse.com” site, which has since been taken down. In addition, a new “Dot Kids” second-level Internet domain was created specifically for content fit for minors under the age of 13.

This article was originally published in 2009. Artemus Ward is professor of political science faculty associate at the college of law at Northern Illinois University. Ward received his Ph.D. from the Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs at Syracuse University and served as a staffer on the House Judiciary Committee. He is an award-winning author of several books of the U.S. Supreme Court and his research and commentary have been featured in such outlets as the New York Times, Los Angeles Times, Associated Press, NBC Nightly News, Fox News, and C-SPAN.