Footnote four of United States v. Carolene Products Company, 304 U.S. 144 (1938) presages a shift in the Supreme Court from predominately protecting property rights to protecting other individual rights, such as those found in the First Amendment.

It is arguably the most important footnote in U.S. constitutional law.

In the 19th century, the Court emphasized the protection of property over individual rights

In the early 1800s, under Chief Justice John Marshall, the Court had first used the contract clause of Article 1 to protect property rights against state and federal regulation.

In Barron v. Baltimore (1833), the Court had held that the Bill of Rights did not apply to the states, leaving the federal judiciary unable to enforce at the local level the freedoms set out in the first ten amendments. Throughout the nineteenth century, the Court therefore emphasized the protection of property more than it did individual rights.

14th Amendment gave heightened scrutiny to economic rights

The Fourteenth Amendment, adopted in 1868, recognized the citizenship of African Americans who had been born in the United States and protected their rights as well as those of others. The amendment limited the ability of states to interfere with the privileges or immunities, due process right, or right to equal protection of citizens.

From the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment until 1938, the Court articulated a variety of new legal doctrines and concepts — including substantive due process, liberty of contract, and economic due process — giving heightened or increased scrutiny to economic rights and regulations.

Lochner era struck down labor-friendly regulations

At the same time, however, it continued to leave the states relatively free to enact laws, without federal judicial oversight, that affected individual expressive rights. This period for the Court, often called the Lochner era, derives its name from Lochner v. New York (1905), in which the Court struck down labor-friendly workplace regulations under the liberty of contract doctrine, over a spirited dissent by Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. The Lochner era continued until the New Deal.

Although the Court initially expressed hostility toward the New Deal’s economic regulation, striking down its provisions in such cases as Schechter Poultry Corporation v. United States (1935), political pressures on the Court and the appointment of new justices began to erode the approach to property and individual rights characteristic of the Lochner era.

Footnote four embodied change from focus on property rights to individual rights

The Carolene Products footnote four embodies this change.

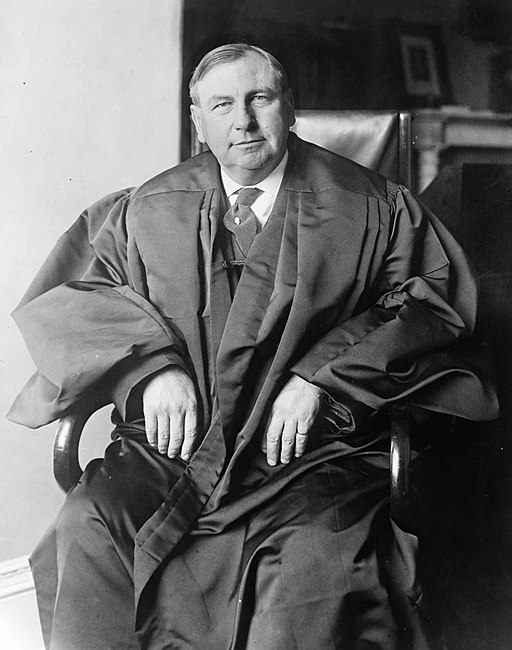

In Carolene Products, the Court upheld a federal law regulating “filled” milk, an imitation or adulterated milk product. In upholding a federal ban on the shipment of this product via interstate commerce, Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, writing for the Court, indicated that the justices would no longer subject economic legislation to heightened scrutiny, but would instead now apply a rational basis test.

He then inserted a footnote, number four, indicating that the Court would, however, continue to apply a form of heightened scrutiny in situations in which a law or statute conflicts with Bill of Rights protections, where the political process has closed or is malfunctioning, and when regulations adversely affect “discrete and insular minorities.”

Footnote four launched a new role for the courts

The language of footnote four launched a new role for the federal courts.

Some justices, most notably Felix Frankfurter, questioned the double standard of review supported by the footnote, but with increasing frequency, especially during the Warren Court of the 1960s, the Court drew inspiration from the note to provide more constitutional protection to individual rights, especially those of the First Amendment.

The footnote defined a role that led the Court to protect voting rights, to invalidate mandatory school prayer, and to enlarge individual free expressive rights.

Footnote four still articulates an important rule affecting how the Supreme Court operates although some argue that the Court under Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist and his successor, John G. Roberts Jr., has adopted a “post Carolene Products” jurisprudence that no longer protects individual rights as much as it did during the Warren Court era.

This article was originally published in 2009. David Schultz is a professor in the Hamline University Departments of Political Science and Legal Studies, and a visiting professor of law at the University of Minnesota. He is a three-time Fulbright scholar and author/editor of more than 35 books and 200 articles, including several encyclopedias on the U.S. Constitution, the Supreme Court, and money, politics, and the First Amendment.