Book banning, a form of censorship, occurs when private individuals, government officials or organizations remove books from libraries, school reading lists or bookstore shelves because they object to their content, ideas or themes. Those advocating a ban complain typically that the book in question contains graphic violence, expresses disrespect for parents and family, is sexually explicit, exalts evil, lacks literary merit, is unsuitable for a particular age group, or includes offensive language. Other complaints have been that the book is written by or deals with sexual orientation or gay issues or brings up topics like slavery that might make individuals uncomfortable.

Children's literature is top target of book bans

Book banning is the most widespread form of censorship in the United States, with children’s literature being the primary target. Advocates for banning a book or certain books fear that children will be swayed by its contents, which they regard as potentially dangerous. They commonly fear that these publications will present ideas, raise questions and incite critical inquiry among children that parents, political groups, or religious organizations are not ready to address or that they find inappropriate.

Most challenges and bans prior to the 1970s focused primarily on obscenity and explicit sexuality. Common targets included D. H. Lawrence’s "Lady Chatterly’s Lover" and James Joyce’s "Ulysses." In the late 1970s, attacks were launched on ideologies expressed in books.

Surge to remove books from school libraries arises again in 2020s

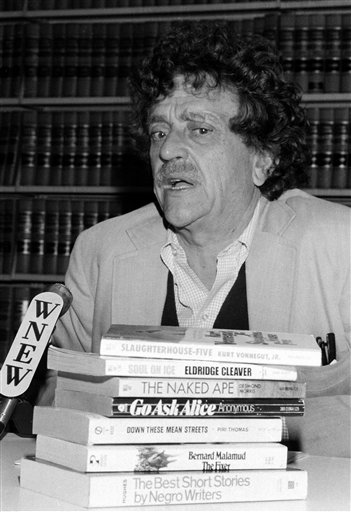

To counter charges of censorship, opponents of publications sometimes use the tactic of restricting access rather than calling for the physical removal of books. Opponents of bans argue that by restricting information and discouraging freedom of thought, censors undermine one of the primary functions of education: teaching students how to think for themselves. In this photo, author Kurt Vonnegut Jr. speaks to reporters on a federal court ruling calling for a trial to determine if a Long Island school board can ban a number of books, including his “Slaughterhouse Five." (AP Photo)

In September 1990, the Thomas Jefferson Center for the Protection of Free Expression declared the First Amendment to be “in perilous condition across the nation” based on the results of a comprehensive survey on free expression. Even literary classics, including Mark Twain’s "Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" and Maya Angelou’s "I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings," were targeted. Often, the complaints arose from individual parents or school board members. At other times, however, the pressure to censor came from such public interest groups as the Moral Majority.

A new surge in book banning have arisen in recent years, with 4,349 recorded instances of book bans from July through December of 2023 (Blair 2024). Most book challenges have come from the ideological right, with Moms for Liberty being particularly active in challenging books (Alter 2024). Often such organizations challenge multiple books at a time. Depending on the state, librarians might have to read and respond to challenges to each book, although some might decide that it is simply easier to remove books. When such books are challenged in public meetings, those opposed to a book may cite isolated lurid passages that may or not be representative of the content of the book as a whole.

According to PEN America, book bans are surging in the United States, especially when books involve topics of sex, sexuality and race. Book bans are more common in the South and Midwest, and are often heavily concentrated intowithin a small group of communities in every state.

Although challenges have occurred throughout the nation, a large majority of such challenges have been concentrated in Texas and Florida, who have been among states to pass new laws governing challenges to books in school libraries. Florida’s governor, Ron DeSantis, gained political notoriety with his “Don’t Say Gay Bill” restricting teaching about sexual orientation or gender identity in certain grades. He also is known for his challenge to accepting advanced credit for African American history absent certain changes in the offering, and by his attacks on diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) efforts.

Similarly, Gov. Greg Abbott of Texas supported and signed a bill in 2023 that banned books that were sexually explicit. One historian has identified laws that seek to suppress information about slavery as being based on the notion (often attributed to liberals) of “fragilism,” or the fear of “extreme sensitivity among the children they aim to protect” (Holton 2024, 202).

Although the Biden administration criticized several book bans and appointed a coordinator to handle complaints, the Department of Education eliminated the coordinator position, dismissed complaints made to the Office of Civil Rights and described book bans as a “hoax” in early 2025. The Trump administration supports various book bans in libraries across the country on the basis of “parents’ rights,” especially with respect to sexually explicit material. Those who oppose book bans argue that the definition of “explicit material” enables biased censorship and discrimination against LGBT students and people of color.

Censorship — the suppression of ideas and information — can occur at any stage or level of publication, distribution, or institutional control. Some pressure groups claim that the public funding of most schools and libraries makes community censorship of their holdings legitimate.

To counter charges of censorship, opponents of publications sometimes use the tactic of restricting access rather than calling for the physical removal of books. Opponents of bans argue that by restricting information and discouraging freedom of thought, censors undermine one of the primary functions of education: teaching students how to think for themselves. Such actions, assert free speech proponents, endanger tolerance, free expression, and democracy.

Community standards may be taken into account in book banning

Although government censorship violates the First Amendment right to freedom of speech, some limitations are constitutionally permissible. The courts have told public officials at all levels that they may take community standards into account when deciding whether materials are obscene or pornographic and thus subject to censor.

They cannot, however, censor publications by generally accepted authors — such as Mark Twain, for example, J. K. Rowling, R. L. Stine, Judy Blume, or Robert Cormier — in order to placate a small segment of the community. Cormier’s "Chocolate War" was one of the American Library Association’s Top 10 Banned Books for 2005 and 2006.

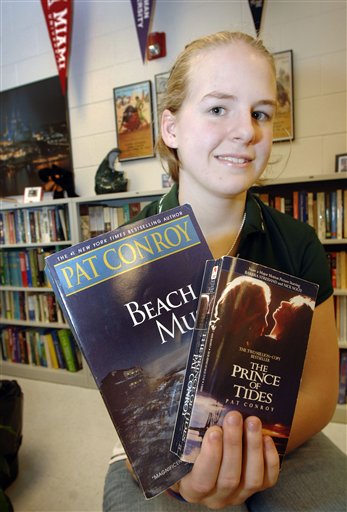

Those who oppose book banning emphasize that the First Amendment protects rights of students to receive ideas. The Supreme Court in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982) ruled 5-4 that public schools can bar books that are “pervasively vulgar” or not right for the curriculum, but they cannot remove books “simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” In this 2007 photo, Makenzie Hatfield, a student at George Washington high school in West Virginia, holds books by author Pat Conroy that were removed English classes after parents of two students complained about their depictions of violence, suicide and sexual assault. (AP Photo/Jeff Gentner)

Opponents of removing books from schools emphasize student rights

Those who advocate removing books from school libraries often focus on parental rights. This becomes problematic, however, when parents of one child seek to prescribe what is appropriate for other children or when public library patrons who do not care to check out a book seeks to deny access to those who do.

Those who oppose book banning emphasize that the First Amendment protects student rights to receive information and express ideas, an idea that was highlighted in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District (1969), when the Supreme Court recognized the right of students to wear black armbands in protest of the Vietnam War.

In the one case to reach the Supreme Court over removing books from school libraries, Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District v. Pico (1982) the court ruled 5-4 that public schools can bar books that are “pervasively vulgar” or not right for the curriculum. But consistent with other rulings related to content discrimination, they cannot remove books “simply because they dislike the ideas contained in those books.” The Supreme Court's decision was, however, narrow, applying only to the removal of books from school library shelves.

Courts more likely to allow limits on age-appropriate material

It is important to recognize that courts are more likely to accept rules limiting school libraries to age-appropriate materials than they are to accept broad bans in public libraries that serve adults. As a practical matter, it might also be worth noting that both children and adults likely have far greater access to controversial materials through online sources than they do through public libraries.

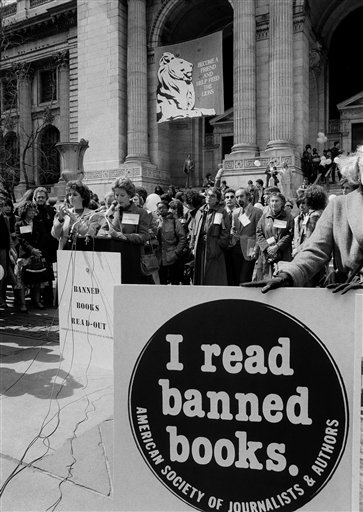

The American Library Association’s Office for Intellectual Freedom documents censorship incidents around the country and suggests strategies for dealing with them. Each September, the American Library Association, the American Booksellers Association, the American Society of Journalists and Authors, the Association of American Publishers, and the National Association of College Stores sponsor Banned Books Week — Celebrating the Freedom to Read.

Designed to “emphasize that imposing information restraints on a free people is far more dangerous than any ideas that may be expressed in that information,” the week highlights banned works, encourages citizens to explore new ideas, and provides a variety of materials to promote free speech events.

The American Library Association publishes the bimonthly Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom, which provides information on censorship, as well as an annual annotated list of books and other materials that have been censored.

Current laws on removing books may be challenged as too vague

In some cases, movements to ban books have stimulated counter movements to preserve access to them. Many of the current laws outlining procedures for banning books are subject to challenge for being overly vague — many, for example, use the term “obscenity” in a much broader fashion than the Supreme Court has recognized in Miller v. California (1973) — or for being overly broad or for having a chilling effect on other publications. Some proposed laws, for example, could be interpreted as allowing for the removal of medical books, or even dictionaries, that might contain depictions, definitions, or descriptions of sexual organs or conditions.

In other cases, like licensing laws that have been struck down, book banning laws may vest undue discretion in public officials. Still other laws, especially those seeking to restrain exposure to discussions of slavery or other historical issues, will likely fail the test of content neutrality. Librarians who face criminal penalties or loss of jobs for failing to remove books, might further be able to raise issues of fair notice and due process.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in April 2024 by John R. Vile, a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. Susan Webb was an adjunct librarian at Southeastern Oklahoma State University.