Billboards are a ubiquitous part of the U.S. landscape. Indeed, in 2005 alone advertisers spent over $6 billion on displaying some 450,000 billboards. Regulation of the location and content of billboards raises many First Amendment issues.

In the realm of First Amendment law, billboards have sparked two main legal controversies. First, to what extent can the government limit access to public billboards, such as on mass transit systems? Second, to what extent can the government prohibit privately owned billboards, such as those appearing on highways?

Court said public billboards were not a public forum

The issue of public billboards flows from whether the advertising space on city-owned public transportation should be recognized as a public forum. In Lehman v. City of Shaker Heights (1974), the U.S. Supreme Court answered in the negative.

The Court held that because of the captive nature of public transportation’s audience, a city could prohibit political advertisements while allowing a myriad of other types. Consistent with its decision in Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo (1974), the Court held that, as the owner of the advertising space, the city could exercise discretion in selling space to advertisers. Such discretion, however, must not be “arbitrary, capricious, or invidious.”

Governments can regulate billboards

Private billboards, like their public counterparts, are open to extensive government regulation of their location. This regulation stems most directly from the desire of various levels of government to preserve the aesthetic value of cities and other localities. In Village of Euclid v. Ambler Reality Co. (1926), dealing with zoning, the U.S. Supreme Court established that a city government could regulate the usage of private property — even without providing owners with compensation.

This decision paved the way for the Court’s 1954 decision in Berman v. Parker. In Berman, the Court ruled for the first time that aesthetic justification alone could permit government regulation of land issues, in this case slum clearance.

Private billboards, like their public counterparts, are open to extensive government regulation of their location. This regulation stems most directly from the desire of various levels of government to preserve the aesthetic value of cities and other localities. In Village of Euclid v. Ambler Reality Co. (1926), dealing with zoning, the U.S. Supreme Court established that a city government could regulate the usage of private property — even without providing owners with compensation. This photo shows the largest single head ever painted on a Broadway billboard in Times Square on the front of the Mayfair Theater in New York, July 14, 1954. The painter of the sign, Patrick Hogan stands on the street to check the piece-meal-painted head against the working sketch. (AP Photo/Carl Nesensohn, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court struck down San Diego ban on noncommercial billboards

The rationale in Berman served in part as the foundation for the Court’s judgment in Metromedia, Inc. v. City of San Diego (1981). At issue in this case was whether the city of San Diego could enact a ban on all off-site commercial billboards. Under San Diego’s ban, businesses could not construct billboards advertising their company or products unless the products or services advertised could be obtained on the same premises as the billboard itself. Noncommercial signs featuring religious symbols or providing time, temperature, and news — among a variety of other exceptions — were permitted, however.

By a vote of 6-3, the Supreme Court held that San Diego’s ban was unconstitutional. Justice Byron R. White led a plurality coalition of justices in arguing that although the commercial ban was acceptable, two aspects of the noncommercial ban rendered the statute unconstitutional.

First, in exempting some types of commercial speech but not providing for analogous exceptions for noncommercial speech, the statute provided commercial speech with elevated protection. This approach, Justice White argued, was inconsistent with the Court’s previous rulings. Second, by specifying what types of noncommercial speech could be placed on billboards, the city was able to make discretionary choices, but, consistent with the Court’s decision in Consolidated Edison Co v. Public Service Commission (1980), Justice White argued that the city could not retain such power.

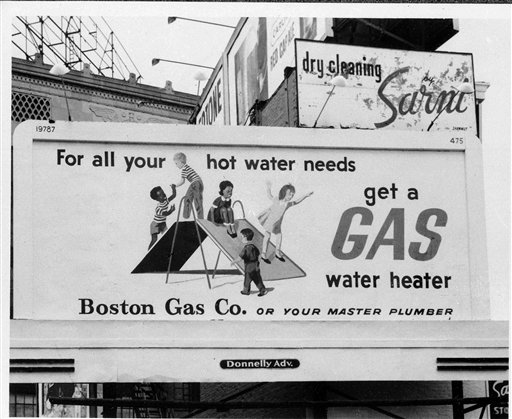

In banning billboards, cities must satisfy separate criteria for commercial and noncommercial content. For commercial content, the city must satisfy the four-prong test offered by Central Hudson Gas and Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980), in which the regulation must directly advance a substantial government interest in a narrowly tailored manner. If noncommercial billboards are prohibited, it must be in a manner that is ultimately neutral to the message being conveyed. This photo shows “integrated” advertising on this billboard put up by the Boston Gas Co. which shows white and black children at play. Photographed Aug. 27, 1963. Location unknown. (AP Photo, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Court said Los Angeles could prohibit political billboards

City Council of Los Angeles v. Tax Payers for Vincent (1984) combined aspects of both Lehman and Metromedia. At issue was whether the city of Los Angeles could prohibit the posting of political campaign advertisements on public property. By a vote of 6-3, the Court held that it could.

In view of earlier distinctions made between commercial and noncommercial speech, Vincent seems to be the closest the Court has come to formally deciding whether an outright ban of billboards is permissible. Lower courts, in assessing all-out bans, have generally accepted the bans as constitutional and tend to give the city or municipality in question broad leeway in justifying the ban — see, for example, Southlake Property Associates Ltd. v. City of Morrow (11th Cir. 1997).

Cities must satisfy criteria to ban billboards

Viewed holistically, the law of billboards suggests a bifurcated approach. In banning billboards, cities must satisfy separate criteria for commercial and noncommercial content. For commercial content, the city must satisfy the four-prong test offered by Central Hudson Gas and Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980), in which the regulation must directly advance a substantial government interest in a narrowly tailored manner. If noncommercial billboards are prohibited, it must be in a manner that is ultimately neutral to the message being conveyed.

Constitutional challenges to billboard regulations have increased significantly after the Supreme Court’s decision in Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015). In Reed, the Court invalidated an Arizona sign ordinance that treated signs differently based on content. The Court emphasized that a law is content-based even if the government’s underlying purpose is not to discriminate against speech. In other words, a facially content-based law is content-based. This photo shows unidentified photographers record the moment as a large billboard advertising the March 29 Academy Awards is unveiled, Tuesday, Feb. 28, 1989, Los Angeles, Calif. (AP Photo/Alan Greth, used with permission from the Associated Press)

Advertisers have tried to circumvent billboard bans

Advertisers, in responding to these bans, have become creative. In communities in which billboards have been prohibited, advertisers may use moving billboards to communicate their messages. These advertisements typically amount to nothing more than a large truck with a giant sign on its truck bed. Traffic-plagued cities such as New York have enacted bans on such advertising-only vehicles. When examined in court, these bans have been sustained as constitutional — see, for example, People v. Target Advertising, Inc. (2000).

Constitutional challenges to billboard regulations have increased significantly after the Supreme Court’s decision in Reed v. Town of Gilbert (2015). In Reed, the Court invalidated an Arizona sign ordinance that treated signs differently based on content. The Court emphasized that a law is content-based even if the government’s underlying purpose is not to discriminate against speech. In other words, a facially content-based law is content-based.

In 2022, the Supreme Court upheld the city of Austin’s billboard regulation that prohibited off-premise digital signs or conversion of them to digital while allowing digital signs that were on the premise of a business and advertised services offered at the business. In that decision, City of Austin v. Reagan National Advertising of Austin, the court said that the city’s review of whether an on-premise sign advertised a good or service offered on the business’ premise was not a content-based decision and therefore did not make the regulation presumptively unconstitutional.

This article was first published in 2009 and has been updated as recently as April 2022. The primary contributor was Ryan C. Black, a Professor at Michigan State University. It has been updated by the First Amendment Encyclopedia.