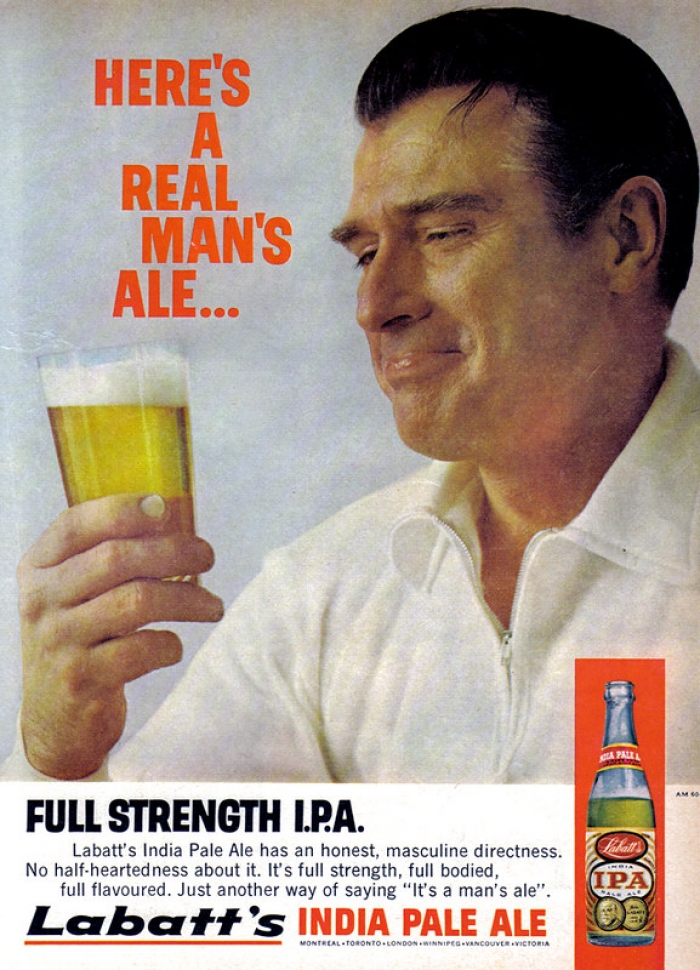

Alcohol advertising involves the marketing of alcoholic beverages through numerous media markets, including print, radio, television, billboards, and the Internet.

States have regulated alcohol advertisements

The Twenty-First Amendment — which repealed the Eighteenth Amendment’s national prohibition against alcohol — gives states regulatory power over alcohol.

Various states and localities have prohibited alcohol advertisements from making false claims and have restricted its placement near schools or college campuses, targeting of minors, and association with athletic prowess.

Alcohol advertising is generally protected by the First Amendment

Due to the commercial speech doctrine developed by the Supreme Court, state regulations of alcohol advertising are subject to careful review. Commercial speech is generally defined as speech designed to convince a target audience to purchase a good or service so that a business or individual can make a profit. The Court first explicitly ruled that truthful commercial speech was protected by the First Amendment in Virginia Pharmacy v. Virginia Consumer Council (1976).

Alcohol advertising, as commercial speech, is protected under the First Amendment as long as it does not promote unlawful activity and is not misleading.

It can be regulated, however, if the government demonstrates that its regulation advances a significant governmental interest and if it narrowly draws it so as not to restrict speech unnecessarily. This test, developed in Central Hudson Gas and Electric Corp. v. Public Service Commission (1980), is often used to determine whether certain types of commercial speech can be restricted.

Court has struck down bans, regulation on alcohol advertising

In Rubin v. Coors Brewing Co. (1995), the Court unanimously struck down a federal regulation prohibiting the display of alcohol content on beer labels. The Court provided even more protection to alcohol advertising and amplified the Central Hudson test in 44 Liquormart, Inc. v. Rhode Island (1996).

In this decision, it rejected as unconstitutional Rhode Island’s “complete ban on truthful non-misleading commercial speech,” in this case on the prices of alcohol and related items.

Regardless, some courts have allowed cities to ban alcohol and cigarette advertising on billboards, which are easily viewed by minors, implicitly accepting city arguments that such advertising increased alcohol consumption and that their regulation was narrowly drawn to advance a compelling government interest. See Anheuser-Busch v. Schmoke (4th Cir. 1996).

Federal departments can restrict alcohol advertising

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF) can restrict deceptive, misleading, or unfair alcohol advertisements.

The Federal Alcohol Administration Act (FAAA) authorizes these agencies to act against untruthful alcohol advertisements and those touting therapeutic or curative values. For example, the ATF often took the position that using athletes in alcohol beverage advertisements is deceptive because it implies that one can enhance athletic performance by consuming such beverages.

Hard liquor advertising was voluntarily banned

Many broadcasters have engaged in voluntary restraint and have generally decided not to direct alcoholic advertising to underage consumers. Television industries voluntarily banned hard liquor advertisements until 1996, but with some cable networks now airing these ads, major network broadcasters may eventually join them.

Some believe that alcohol advertising should be banned or restricted because it encourages alcohol consumption, which can be detrimental to the public health.

Others point out that hard liquors have been singled out for a voluntary ban while the beer and wine industries freely advertise in all media. They claim this is discrimination and is not content neutral.

Like the wine industry, the spirits industry notes that one drink a day can have health benefits for adult men and women. The courts so far have been unwilling to allow regulations that do not meet the Central Hudson test, thus total bans on alcohol advertising are unlikely to pass constitutional muster.

This article was originally published in 2009. Ruth Ann Strickland was a professor at Appalachian State University.