Few if any scientific figures are better known, or have had a greater impact on modern science, than Albert Einstein, a theoretical physicist who was born in Germany in 1879 and died in the United States in 1955.

Einstein was best known for his theory of relativity and for the idea, for which he received a Nobel prize in physics, that light traveled both as particles and waves. His theories paved the way for the development of nuclear weapons that helped bring an end to World War II.

Einstein held positions at numerous European colleges and universities prior to moving to the United States and settling at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University. He had a fundamental awe of creation and for the laws of nature, which he believed could be attributed to God. He did not practice his Jewish faith, which nonetheless made him unwelcome in his home country of Germany. Moreover, although he later favored the establishment of a Jewish homeland, he had serious reservations about nationalism, supported pacifist causes, and was a strong proponent of intellectual freedom.

Einstein opposed dictatorships in Germany, Russia

A proponent of democratic socialism, Einstein was a strong opponent of dictatorial regimes on both the right (Nazi Germany) and the left (Stalinist Russia), and he became a U.S. citizen in 1940. In the 1950s Einstein became quite concerned over the congressional investigations spearheaded by Wisconsin Senator Joseph McCarthy and designed to embarrass and root out individuals because of their past political associations and beliefs.

As one who admired Mahatma Gandhi, Einstein generally believed in nonviolent action to redress political grievances. In counseling Rose Russell, a member of the New York City Teachers Union, and physicist Al Shadowitz who had been called to testify before Congress for their past political associations, Einstein advised that they should rely on the First Amendment freedom of speech rather than on the Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination (Einstein 1953).

Einstein spoke about concerns of academic freedom

During this same era, in which Einstein was a member of thee American Association of University Professors, he indicated that he understood academic freedom to consist of “the right to search for truth and to publish and teach what one holds to be true” (Reichman 2017). He further indicated that “The threat to academic freedom in our time must be seen in the fact that, because of the alleged external danger to our country, freedom of teaching, mutual exchange of opinions and freedom of press and other media of communication are encroached upon or obstructed” (Reichman 2017).

Deeply valuing his U.S. citizenship, Einstein that that “The strength of the Constitution lies entirely in the determination of each citizen to defend it. Only if every single citizen feels duty bound to do his share in this defense are the constitutional rights secure” Reichman 2017). Providing further explanation of his advice to fellow scholars, Einstein says that it was important for intellectuals to refuse “to cooperate in any undertaking that violates the constitutional rights of the individual. This holds in particular for all inquisitions that are concerned with the private life and the political affiliations of the citizens” (Reichman 2017).

Perhaps in part because he had seen racism in action in Germany, Einstein was a strong supporter of civil rights for African Americans and other minorities.

A biographer of Einstein notes that he was defined by his curiosity and that his “fundamental creed was that freedom was the lifeblood of creativity” (Isaacson 2007, 548, 550).

After death, Einstein photo was at center of right of publicity case

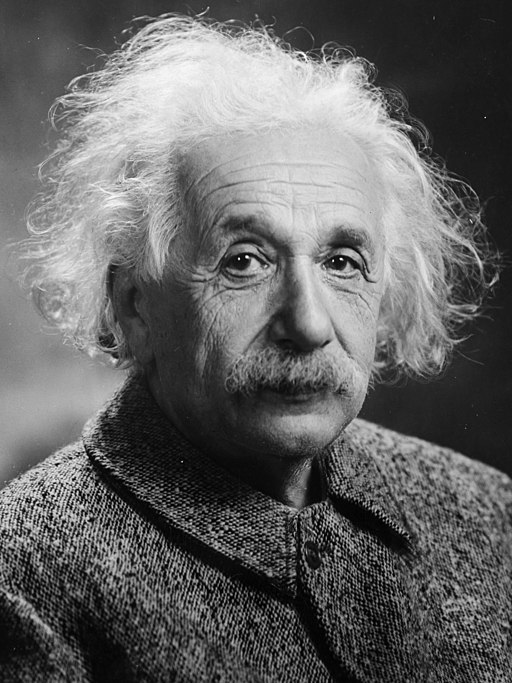

Einstein’s image, with a mustache and unruly hair, is almost universally recognizable. In 2009, People Magazine published an advertisement for a crossover vehicle by General Motors Co. portraying Einstein as a hip-hop icon.

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, which held Einstein’s intellectual property rights, sued for violations of the right of publicity but lost in a California court on the basis that even if Einstein had a right to avoid misappropriation of his likeness, the limit to assert such rights did not last more than 50 years beyond his death (Gan 2013).

John Vile is a professor of political science and dean of the Honors College at Middle Tennessee State University. This article was published on Dec. 15 2023.