Abortion has been one of the most contentious and volatile issues in the United States, igniting public protest for and against it.

In essence, there are two rights at stake: the privacy rights of patients and staff members at health care facilities that provide abortions and the rights of speech, assembly, and petition of abortion protesters.

Protests outside of clinics that provide abortions ramped up after the 1973 Supreme Court decision in Roe v. Wade that protected a woman's right to abortion. Even after the Supreme Court overturned these rights in 2022 in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, allowing states to outlaw abortions, protests have continued in states where abortion is legal.

Abortion protestors have First Amendment speech rights

Some states and cities have sought to stop abortion protesters from blocking entrances to clinics or bothering women going in, as have clinics themselves. Through a series of decisions beginning in the 1990s, the Supreme Court has outlined when and where free speech rights can be restricted.

The standard of strict scrutiny when applied to First Amendment rights generally requires that the state demonstrate a compelling government interest to prohibit speech based on content in a public forum. If the regulation of the speech is neutral in terms of content, the regulation must only pass a reasonable scrutiny test. These standards were tested in the first abortion protest case to reach the Supreme Court in Madsen v. Women’s Health Center (1994).

In this case, a Florida state court permanently enjoined abortion protesters from blocking or interfering with public access to a clinic and from physically abusing persons entering or leaving. An amended injunction subsequently excluded demonstrators from a 36-foot buffer zone around clinic entrances and driveways. Government officials sometimes use buffer zones to attempt to mitigate the effects of protesting by separating protesters and their targets in designated areas.

In Madsen, the Supreme Court established a new test for injunctions prohibiting speech: an injunction will be upheld unless it burdens speech more than is necessary to serve a significant government interest. Justice Antonin Scalia argued in a dissent that this new standard was not strict enough and represented a grave threat to First Amendment protections. He also argued that the majority decision was biased against anti-abortion speech.

However, the majority held that the injunction was not subject to heightened scrutiny based on content simply because it applied to anti-abortion protest. It upheld the restrictions against demonstrating within the buffer zone around the clinic and from making loud noises within earshot of the clinic. It rejected the prohibition against approaching patients within 300 feet of the clinic.

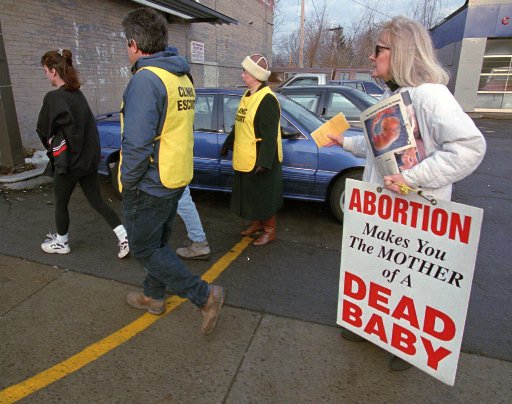

In Schenck v. Pro-Choice Network of Western New York (1997), the Court upheld a fixed buffer zone in the context of anti-abortion speech, but struck down a floating buffer zone, considering it too broad and difficult to enforce. In this photo, an anti-abortion protester, right, identified as Linda Palm, talks to and tries to give a brochure to a patient, far left, surrounded by clinic escorts, as they enter a “fixed buffer zone” marked by a yellow line at the Buffalo GYN Womenservices, Feb. 21, 1997, in Buffalo, New York. (AP Photo/Bill Sikes)

Some laws protect abortion clinics

Later, in response to a wave of violence surrounding protests at abortion clinics, President Bill Clinton signed the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act of 1994 (FACE). This law prohibits acts of violence at abortion clinics by making it a federal crime to use force or threat of force, physical obstruction, intentional injury, and intimidation against reproductive health care providers and their patients. It also authorizes civil lawsuits for injunctions against such activities and monetary damages. The penalties for violation include imprisonment and fines. To protect First Amendment rights, the law said it could not be construed to prohibit peaceful expressive conduct or any activities protected by the free speech and free exercise clauses.

Abortion rights activists applauded the law as a protection for clinics and patients, but First Amendment watchdogs criticized it as too broad and as improperly distinguishing between violent and nonviolent protest.

Court addressed buffer zones

Three years after buffer zones were upheld in Madsen, the Supreme Court again addressed the issue of buffer zones in the context of anti-abortion speech in Schenck v. Pro-Choice Network of Western New York (1997). Doctors and medical clinics filed a lawsuit against anti-abortion organizations that engaged in heated demonstrations and blocked access to clinics. The federal district court issued an injunction against the protesters prohibiting them from demonstrating within 15 feet of clinic entrances and driveways, making this a fixed zone, and 15 feet of patients and their vehicles, creating a floating zone.

In a 6-3 vote, the Supreme Court upheld the fixed buffer zone but in an 8-1 vote struck down the floating buffer zone. Using the test developed in Madsen, the Court found that the fixed buffer zone did not burden speech more than necessary to serve the government’s interests. It, however, considered the floating buffer zone too broad and difficult to enforce. Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist’s opinion reasoned, “the 15-foot floating buffer zones would restrict the speech of those who simply line the sidewalk or curb in an effort to chant, shout, or hold signs peacefully.”

In 2000, the Court addressed buffer zones and floating bubbles in Hill v. Colorado, another anti-abortion speech case. In 1993, the state of Colorado passed a statute mandating that within 100 feet of a medical facility, protesters intending to counsel or distribute literature must have permission from passersby before approaching them within 8 feet. The statute created buffer zones similar to the fixed buffer zones and floating zones at issue in Schenck. Indeed, the first time the case came before the Court, the justices remanded it in light of Schenck. The Colorado Supreme Court upheld the statute and interpreted the floating zone narrowly. A violation of the floating zone occurred only if the speaker physically moved within 8 feet of the passerby but not if the passerby approached the protester.

In a 6-3 decision, the Supreme Court upheld the Colorado court’s decision. The majority opinion, written by Justice John Paul Stevens, held that the statute did not violate the content-neutrality test under Ward v. Rock against Racism (1989), because the regulation affected the location of the speech rather than its content and applied to all protesters regardless of viewpoint. Further, the 8-foot zone did not violate Schenck because the protestors can communicate at a “normal conversational distance” to a passersby. Dissenting, Justice Scalia argued that the restriction was content-based and placed an unjustifiable burden on free speech.

In this photo, anti-abortion activists hold mock caskets and placards showing the number of abortions performed each year during an anti-abortion demonstration in Washington, Jan. 22, 2003. Thousands of abortion opponents marched to protest the 30th anniversary of the Roe vs. Wade decision that legalized abortion. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak)

Are coordinated abortion protests racketeering?

Scheidler v. National Organization for Women (2006) stands as one of the most well-known and contentious abortion protest cases. It reached the Supreme Court three times. Its importance rests in the claim by the petitioners that abortion protest violates the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act (RICO) and the Hobbs Act.

The petitioners argued that anti-abortion activity was a nationwide conspiracy to shut down abortion clinics through racketeering and extortion. The Supreme Court first heard the case in National Organization for Women v. Scheidler (1994). The lower courts had dismissed the case, arguing that RICO required an economic motive and that abortion protests did not satisfy this requirement.

The Supreme Court overturned this decision arguing that economic motive was unnecessary and that although the protesters did not gain financially, they did affect the business of the clinics. Anti-abortion groups denounced the decision, and other civil liberties advocates worried that the decision undercut the First Amendment freedoms of other protest groups.

Nine years later, the case returned to the Supreme Court as a class action suit in Scheidler v. National Organization for Women (2003). The lower courts found that the actions of Scheidler were racketeering in violation of the Hobbs Act and issued an injunction against the anti-abortion groups as well as substantial monetary fines. Scheidler appealed on several grounds, including violations of the free speech clause under the First Amendment. The Supreme Court refused to consider the free speech issues. The Court ruled that while the actions may have been coercive, they did not amount to extortion because the defendants did not obtain property from the plaintiffs, and RICO did not support the injunction. Although not based on First Amendment grounds, the decision was viewed as a victory for abortion protesters.

The Court ruled on this case for a third time in Scheidler v. National Organization for Women (2006). The Court ruled 8-0 that physical violence unrelated to robbery or extortion was outside the Hobbs Act, saying that Congress did not intend to create “a freestanding physical violence offense.” Instead, Congress had addressed violence outside abortion clinics in 1994 through the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances Act. Of note, social activists and the AFL-CIO sided with the anti-abortion demonstrators in this case, arguing that injunctions based on extortion law could be used to thwart protests for better wages and working conditions.

Court finds 35-foot buffer zone was too large

In McCullen v. Coakley, 573 U.S. ____ (2014), the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously struck down a Massachusetts law that prohibited individuals from standing on a public sidewalk within 35 feet of an abortion facility. The court said the buffer went far beyond the limits that it had accepted in Hill v. Colorado. It based its decision in part on the fact that the more restrictive regulations in Massachusetts interfered with the rights of individuals using traditional public fora (public walkways and sidewalks) to engage in discussions with those entering abortion facilities.

In 2025, the Court declined to to hear a pair of cases from abortion opponents who said city ordinances in two states limited anti-abortion demonstrations near clinics, violating their First Amendment rights. One of the cases had arisen from Englewood, New Jersey, where the city had an 8-foot demonstration free zone. Activist Jeryl Turco said the zone also prevented her from approaching women near a clinic to try to persuade them not to have abortions. The other ordinance challenged was in Carbondale, Illinois, where a clinic was receiving more abortion patients coming from adjacent states that had outlawed them. The city repealed the ordinance before the case went to the Supreme Court.

This article was originally published in 2009 and updated in 2025. Lynne Chandler Garcia is an associate professor of political science at the U.S. Air Force Academy. Her areas of research include Constitutional interpretations, the concepts of personhood, civil discourse, empathy in political behavior, foreign policy, military operations, and the art of pedagogy for underprivileged learners.